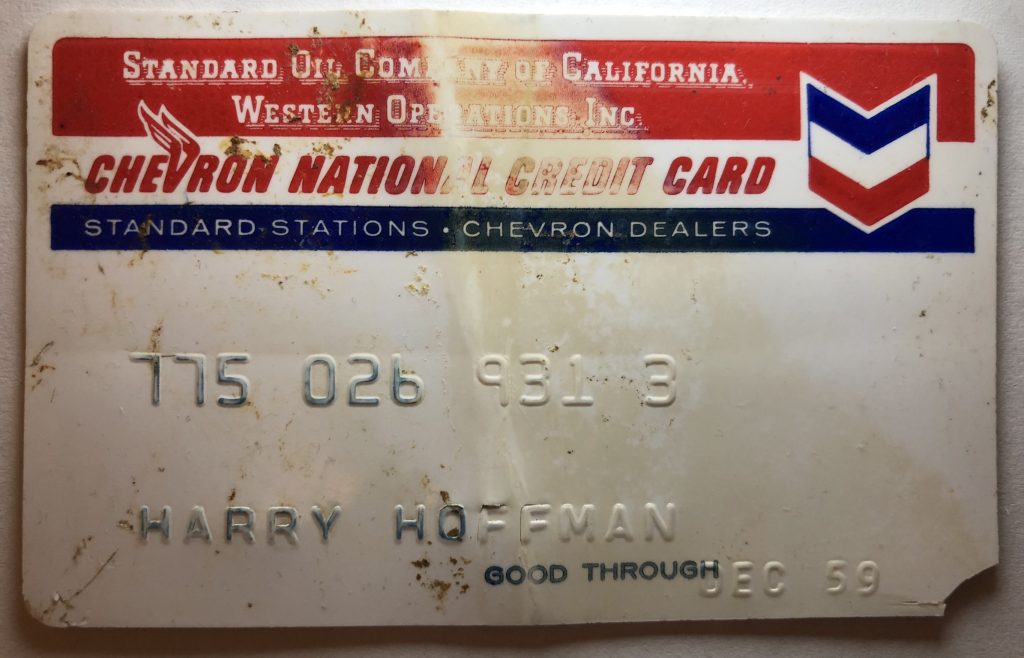

Jeff Christner spots the folded credit card from several feet away. The white plastic pokes out from layers of crumbling sandstone, disintegrating cloth and glass. Christner brushes off decades of dust to reveal the card holder’s name: HARRY HOFFMAN. The card expired in December 1959.

Hoffman probably threw out the card with little thought. The card was dumped into what was likely an unauthorized trash dumping site on top of the scenic bluffs at Mussel Rock, just south of the official Mussel Rock Landfill, which served the rapidly growing San Francisco suburb of Daly City from 1957 to 1978. Now, perfectly preserved credit cards, toy figurines, toothbrushes and plastic bags have begun to spill out of the eroding cliff wall, at risk of falling into the ocean below.

Jeff Christner and his son Paxton have been scouring the coast at Mussel Rock for trash for a decade. Spotted with marine debris, day-old trash and 60-year-old landfill refuse, this coastline on Pacifica’s border is a microcosm of our global trash problem. The Christners’ monthly hauls tell an alarming story about the persistence of plastic, which is filling the oceans.

While plastic particles have been discovered in Arctic ice, bottled beer and even the fish we eat, the ecosystem level consequences of a plastic-filled ocean remain unknown.

“We’re conducting an unintentional experiment on ourselves and on the planet that is not going to end well. And we’re only just really becoming aware of that,” said Edward Humes, author of “Garbology: Our Dirty Love Affair with Trash,” in an interview.

Finding time capsules in trash

To Jeff Christner, each landfill item is a treasured look into the past. Among his favorite finds are a miniature toy sniper and a Native American figurine who sits atop his horse, both vestiges of a previous era in which kids played pretend battle with plastic figures instead of video games.

The Mussel Rock Landfill was always ill-fated, said Shawn Heiser, a geographer and librarian who has studied the site. Rushed to deal with the refuse of a rapidly expanding population in Daly City, planners failed to assess the site’s obvious problems.

Mussel Rock is home to the second largest active landslide in California, which has slowly carried the landfill’s contents toward the Pacific Ocean. The San Andreas fault crosses the California coast just a quarter mile to the north, occasionally accelerating the slide with earthquakes and tremors. Meanwhile, the shoreline is rapidly eroding. During wet years, several feet of the sandstone cliff falls into the ocean, taking trash with it.

“It doesn’t take a lot of logic to think that putting garbage into a landfill on top of a landslide and a fault is going to produce problems,” said Heiser.

After two decades of operation, Daly City finally closed the doomed landfill in 1978. Since then, the city has spent about $10 million toward efforts to contain the old garbage’s slow march toward the ocean, according to John Fuller, the city’s director of public works.

Fuller said in June that his department was not previously aware that refuse was spilling out of the cliff wall at the site just south of the official boundary of the landfill. In early September, Fuller said the department had photographed the site with a drone but still had no plans to keep more of the trash from falling into the ocean.

“We are regularly inspected by the Water Resources Control Board and Coastal Commission staff and are in compliance with all mandates for maintenance and monitoring of the site,” Fuller added.

The Bay Area has long struggled to manage the waste produced by its dense population. Along with keeping trash and toxins from escaping landfills, scientists worry about the trash that never makes it to landfill, ending up instead in the San Francisco Bay and its surrounding waterways.

“The Bay can really trap persistent pollutants like plastic. Some parts of the Bay do not see a lot of ocean exchange,” said Rebecca Sutton, a senior scientist at the San Francisco Estuary Institute who is leading a two-year study on plastic pollution in the Bay. Her previous research there found alarming concentrations of microbeads from cosmetic products, which have since been banned in the United States.

Debris from across the Pacific

Half-century-old garbage is not the only relic of a distant society that the Christners have found at Mussel Rock.

In July 2015, the father and son from Pacifica noticed a green plastic crate with Japanese characters that had washed up at Mussel Rock during a monthly beach clean-up. With help from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Japanese Consulate, they traced the crate back to a Japanese fisherman who had survived the devastating tsunami of March 2011, according to Sherry Lippiatt, a regional coordinator for NOAA’s Marine Debris Program.

The crate was one of 72 confirmed pieces of tsunami debris – including a fully packaged Harley Davidson – that washed along the Pacific coast, Lippiatt said.

The crate started its journey at Yamada Port, Japan, nearly 5,000 miles from Mussel Rock, but its actual route through the Pacific was much longer. Left at sea, it could take hundreds of years for sunlight and currents to break a crate like that into microplastics, which are tiny pieces of plastic measuring less than 5mm in diameter. Scientists say that those microplastics may never fully biodegrade in nature.

Plastic pollution is a global issue

Although the problems of the Mussel Rock landfill are rare in the United States, it is a common sight across the globe. In island communities, dumps are often located on coasts, vulnerable to erosion and sea level rise according to Carolynn Box, science program director of 5 Gyres Institute, a research and advocacy nonprofit focused on ocean pollution.

Quantifying just how much plastic the ocean contains is no simple task.

In 2014, researchers estimated that over 250,000 tons of plastic litter the ocean’s surface in the form of over 5 trillion plastic particles.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an immense area of the Pacific ocean where rotating currents trap large volumes of plastic, now figures at three times the size of France and is “increasing exponentially,” according to a study published in Scientific Reports in March.

The deep sea is a completely different story, one that has attracted less attention than beaches and gyres. Scientists at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute found in 2013 that a third of the trash in Monterey Submarine Canyon was made of plastics – half of which were plastic bags.

Garbology author Humes sees our dependence on single-use, disposable products as a main driver of plastic pollution.

“Twenty-five percent of our waste stream… is packaging and containers, the stuff that we just throw away right away,” said Humes in an interview, referring to the United States. “[It’s] instant trash and yet lasts forever.”

One man’s garbage

On a recent Saturday at Mussel Rock, the Christners filled another bucket with waste. Among the morning’s haul were a toy plate from the late 1950s, a sealed glass bottle labeled “LIQUOR” from around the same time that still contained drops of alcohol, fishing buoys, heavy-duty nylon rope and beer cans left by recent beach visitors.

At Mussel Rock, where the Christners are uncovering garbage almost as old as our addiction to disposable plastic conveniences, there’s an important lesson: though we may forget about plastic the moment we dispose of it, it never really disappears.

Scientists have proposed ambitious solutions to reduce the pile-up of persistent ocean plastics, such as plastic-eating bacteria, robots that suck up floating trash in the oceans and ejecting trash into space. But cleaning up this mess can only get us so far, said Sherry Lippiatt of NOAA.

“If your bathtub is overflowing, are you going to grab a mop or turn off the tap?” Lippiatt asked.

This story was published in the October 2018 edition of Pacifica magazine, in partnership with the Half Moon Bay Review.