When Sarah Goody was told she’d fail freshman year if she kept striking for the climate every Friday, she moved her protests to after school. The Marin local, 14, has been an environmental activist since she was 11. This year she joined the Fridays for the Future movement, led by Greta Thunberg, the 16-year-old from Sweden who has received international attention for her climate activism.

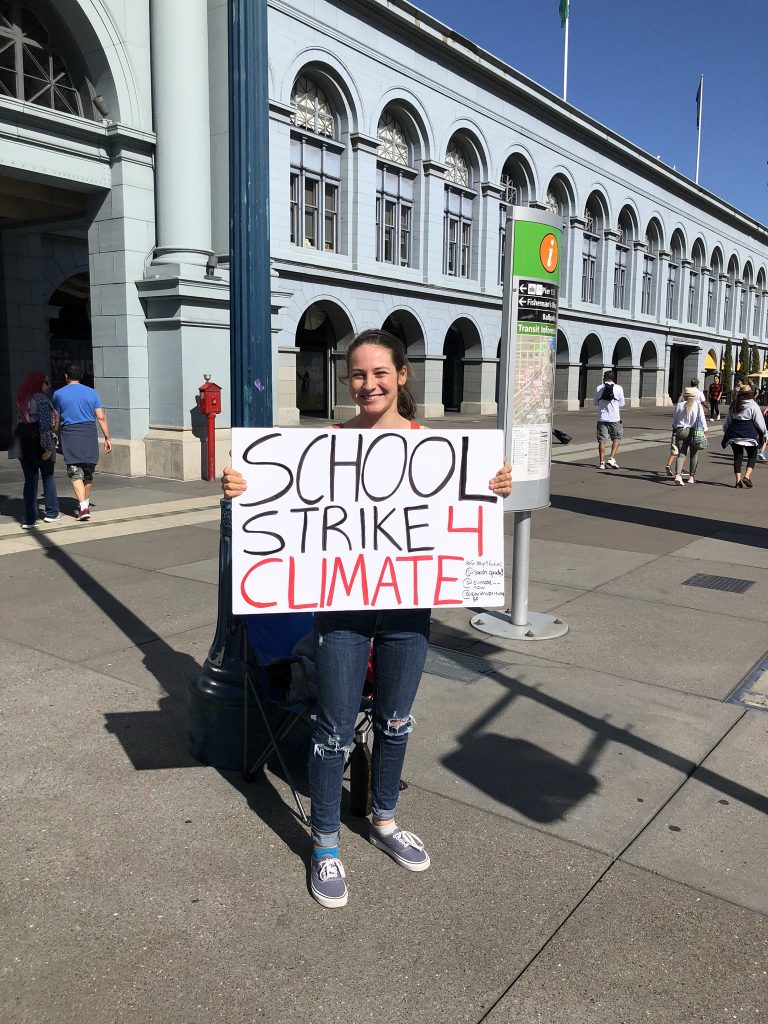

Like Thunberg, Goody most often strikes alone. For a while, she sat by herself outside San Francisco City Hall every Friday. She always brings the same sign: “School Strike 4 Climate”—just like Thunberg’s, except in English rather than Swedish. But after feeling like she was photobombing weddings more often than sparking inciteful conversation, she decided to strike more locally, in Marin County. Now every Friday she’s outside of a high school, embodying the intergenerational nature of the movement. She strikes next to Seniors for Peace, a group of senior citizens that have been protesting weekly on social justice issues since 2004. It helps to strike a little closer to home — Goody still has a few more years to go before she can get her driver’s license.

Goody is one in a growing crowd of Bay Area youth climate activists. Youth leaders were some of the critical organizers of the local September climate week, where 40,000 people were out in the streets of San Francisco, a portion of the estimated 7.6 million who struck globally in support of more governmental action to prevent climate change.

September was hardly the end to the action: groups are gearing up for the next national climate strike on Dec. 6, which will coincide with the United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP25 in Madrid.

In the meantime, actions in the Bay led by both youth and adults have been ongoing with targeted protests outside of banks and the development of new programs, including one that offers paid internships for Youth Climate Ambassadors in the City of San Mateo. And there have been policy wins, like 350 Bay Area (in a coalition with other organizations) helping Berkeley become the first U.S. city to ban the use of natural gas in new homes starting in 2020, a move that has spread with similar policy in Palo Alto, Menlo Park, San Jose, Mountain View, and more.

These actions are garnering more and more attention: this week, Collins dictionary announced “climate strike” as their 2019 word of the year. And the Bay Area will be hard pressed to forget Thunberg anytime soon — a 60-ft, hyper-realistic mural of the teen was unveiled this week in San Francisco, on Mason Street near Union Square.

As the movement grows, it diversifies. Isha Clarke, a 16-year-old from West Oakland, was drawn to the movement after she learned about environmental justice: “When I heard ‘climate change,’ I was like, yeah, that’s a white issue. I don’t have to deal with that. I’m not with saving the polar bears or saving the rainforest–I thought that’s what the fight was.”

Then, Clarke, who is African-American, attended her first climate protest, fighting development of a coal terminal through West Oakland, two and a half miles from her home, in a predominately low-income community of color. “In that moment, I realized what environmental racism is. And how central it is to environmental injustice and the fight for reversing climate change.”

Clarke has seen the growth of the movement first hand, from her work with Youth vs. Apocalypse, a diverse, youth-led organization. “At the first strike that we organized there were 2,000 people, and we were blown away.” Six months later, at the September climate strikes they helped organization in collaboration with groups across the nation, there were 40,000.

Now, as activist organizations continue to strategize their plans moving forward, many leaders are pushing for more radical action. Caroline Choi, a 17-year-old activist from Alameda, believes that youth involvement is the key. “I think as youth we have the freedom to be as a radical as we need to be and look out for our own futures,” she said.

Clarke agrees. “I think young people deserve to be leading a movement that is all about our futures. And on top of that, I think it really needs to be led by youth of color, youth of color from low-income communities and indigenous communities. Because like the kids in West Oakland, they’re experiencing that every single day.”

Choi thinks adults get bogged down in reputation and are more easily rattled by online attacks—especially those from right-wing Tweeters. “With climate kids, we’re not really on Twitter. We don’t care what the right-wing is saying. We haven’t been touched by stuff like that.”

There are adults behind the scenes supporting these teens—such as those at 350 Bay Area, the parent organization to Youth vs. Apocalypse. Laura Neish, executive director of 350 Bay Area, says the kids are doing their own work, and the adults just help with the logistics.

“I feel like the adult climate organizers are really wanting young people to tell them what to do,” Clark said.

However, the politicians they’re targeting are less receptive. Clarke gained fame earlier this year when a video of her and a group of young activists asking Senator Diane Feinstein to support the Green New Deal (and getting turned down) went viral.

There are some wins, though. This summer, the head of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries called the youth-led climate strike movement the “greatest threat” to the fossil-fuel industry, in an interview with Agence France-Presse.

“They may not respect our voice, but they fear our voice,” Clarke says.

Youth leaders are calling on adults to listen and respond. Choi says it’s frustrating to be offered awards and kudos from adults without seeing change happen on a tangible, policy level. Last month, Thunberg declined the 2019 Nordic Council Environment Prize, stating on Instagram: “The climate movement does not need any more awards. What we need is for our politicians and the people in power start to listen to the current, best available science.”

Bay Area teens are grappling with the complexities of awards, too. Clarke was the recipient of the 2019 Brower Youth Award, which recognizes six “emerging youth leaders in the environmental movement” across the country.

“I really agree with Greta’s stance that we don’t need awards, we need action,” she said. But, she says, at the same time, she finds that adults take her more seriously knowing she’s received a significant award. “Especially as a young person, as a young woman of color, I can walk into a space and be like, ‘I’m a recipient of the 2019 Brower Award’ and people are like, oh, okay, what she’s saying is for real.”

Choi, who won the Harvard Consulting on Business and Environment Student Sustainability Award, said the awards are issued prematurely. “Sometimes we’re awarded for things like they’re accomplishments, when really the goal that we’re working towards hasn’t been accomplished yet.”

So the climate kids just keep working. They have group texts, Snapchats, and GroupMes. They take video conference calls on Zoom. For summer camp, they might attend Youth Empowered Action Camp (like Goody did) to learn strategic organizing as a form of summer fun instead of, say, waterskiing.

Choi uses her free periods at school to catch up on emails and jump on calls, and Goody says she spends four to five hours a day on activist work.

They still have homework and extracurriculars to participate in—fencing and dance, in these cases—and make sacrifices when necessary. Goody quit high school theater this year, when the organizing needed for the September actions felt more urgent than rehearsals for her high school production of Head over Heels. And Choi spent her Halloween with Extinction Rebellion, the international climate action group, rather than partying or trick or treating like many of her friends.

Choi says that this Halloween, protesting was exactly where she wanted to be. “We want people to remember the apocalypse is coming, as scary as it sounds,” she said.

On Halloween in Berkeley, Extinction Rebellion held a funeral for extinct species and victims of the climate crisis. In between trick or treaters, the activist procession marched carrying a coffin with the Extinction Rebellion logo and signs reading: “Climate Chaos or Survival?”

These youth leaders know it’ll be a long fight. Choi has questioned whether it makes sense for her to apply to college next year, when she could “just focus on this huge issue that might make my college education obsolete in the future. Eventually, no amount of money that you make is gonna protect you from this crisis.”

Anna Goldings, founder of Extinction Rebellion Berkeley and sophomore at the university, says that the crisis is “giving her life purpose.”

Goody believes “activism is a lifelong career. It’s something you can continue working at, no matter your age, no matter your position in life.”

Clarke says, “I feel like there’s no other option but to continue at this point. We only have so much time. I couldn’t do nothing as I watch the world crumble.”

Whether they planned it or not, the climate kids are committed for life. They’ll keep meeting and they’ll keep striking, one Friday at a time.