Palo Alto’s city council voted against further discussion of new measures that would address the housing affordability crisis in the city even as soaring rents have displaced community members like teachers, first responders and service industry workers.

While cities around the peninsula have passed rent control or approved new affordable housing projects to address the problem, the Palo Alto City Council voted 6-3 on Oct. 16 against studying stabilization measures after hearing passionate testimony from 60 members of the public.

Teachers in Palo Alto are having to commute from Gilroy, Capitola and Dublin, which means that they are less often available to participate in school events like sporting games and dances, says Teri Baldwin, president of the Palo Alto Educators Association, who spoke at the meeting.

“Important members in our community such as teachers, nurses, shopkeepers and many more are being priced out and driven away,” Baldwin said.

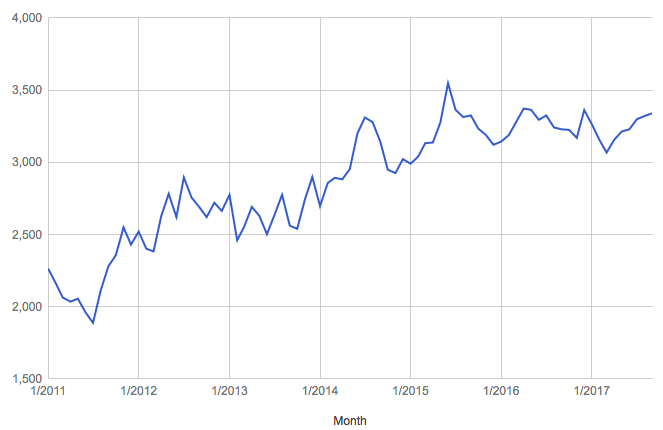

Members Tom DuBois, Karen Holman and Lydia Kou wrote to their colleagues last month that rising housing costs are unsustainable when compared to wage growth in the city. They noted that average monthly rent prices have increased by 50 percent since 2011 while median income has grown at one-tenth that rate.

The council members argued that the city’s tenant protections don’t meet the needs of renters, who occupy 45 percent of housing units in Palo Alto, according to 2015 census data.

To address this problem, the council members wanted to discuss possibly enacting a new percentage cap on rent increases for buildings of five or more units, protecting tenants against termination without just-cause and updating existing renter protections.

“We’re really just asking the council tonight to take this up as an important issue,” Member Tom DuBois said before the council voted against studying more renter protections. “I think it’s an important enough issue that the council should take it up, and not really even refer it to a subcommittee.”

Current protections in Palo Alto include a tenant-landlord mediation program that provides a professional mediator to handle disputes between tenants and landlords. As well, the city requires landlords to notify tenants with month-to-month leases of a rent increase at least 30 days in advance. The city also provides guidelines for how landlords should handle deposits and provide adequate living conditions.

But there is no limit on how much a landlord can raise rent prices in Palo Alto. And for one-year leases, there is no requirement that landlords give notice of rent increases in advance of the termination of the current lease, according to the City of Palo Alto tenant guide, updated in January 2015.

After Teri Baldwin’s Palo Alto apartment complex was bought by new owners, they surprised her with a 30 percent rent increase one month before her lease expired. “This [was] my home, I work close… I want to stay, I just can’t afford that high of an increase right now.” Fortunately for Baldwin, she found an affordable apartment in nearby Mountain View.

In Palo Alto, landlords can choose not to renew a lease after it expires for any reason. Just-cause protections, which several Bay Area cities like East Palo Alto have, dictate specific grounds for a landlord to terminate a tenancy, ranging from failure to pay rent to continued disorderly conduct.

But the members’ suggestions to strengthen protections divided the council.

“This will have the perverse effect of doing the opposite of what you want to achieve,” said Mayor Greg Scharff, who voted against the proposal.

Palo Alto’s housing struggles come as nearby cities are also grappling with the issue of affordability. While the council and public speakers were deadlocked on how to even define the problem – whether it is a matter of too little supply or not enough renter protections – the nearby city of Mountain View took action. Last year, it voted in favor of Measure V, which stabilizes rents and provides just-cause eviction protections. Now, Mountain View landlords can’t raise rents by more than 3.4 percent annually.

Other cities, like Menlo Park, have opted to address the problem through increasing the supply of housing and creating tenant-landlord mediation programs that give tenants and landlords an opportunity to discuss disagreements in a facilitated environment.

Daniel Saver, senior attorney who works in the housing program at Community Legal Services in East Palo Alto, said stabilization measures like Measure V in Mountain View help tenants against “economic eviction,” or dramatic rent increases meant to force tenants out.

“So whereas it used to be common in Mountain View to see rent increases of $400 or $700 a month, people are now getting increases of $50 a month or $75 a month, which is much more manageable,” Saver said in a phone interview.

Saver added, “I would say rent stabilization and just-cause are the absolute most effective methods of stemming the tide of displacement.”

But opponents of new rent stabilization measures, such as real estate brokers and local landlords, asked the council to consider increasing the supply of housing, which they say is the key to addressing rising rents.

Harold Davis, whose family has owned and operated apartment buildings in Palo Alto for 50 years, said at the Oct. 16 meeting that “rent control regulations eventually result in landlords being unable to keep up with rising maintenance costs, which over time leads to buildings being dilapidated.”

Instead of “rent control,” Davis said, the city should focus on “streamlining and speeding the process for approval of new apartment developments, and removing the 50-foot height limit to allow more density and more units to be built.”

In a May 2017 study, the Institute of Governmental Studies at UC Berkeley found that a third of families that were displaced – meaning they were priced out by market conditions, harassed out by landlords, or pushed out by poor housing conditions – left San Mateo County entirely, opting for the Central Valley or the East Bay instead.

The current average price for a two-bedroom apartment in Palo Alto is $3,670, up from $3,364 in January 2017.

Lynn Krug, chair of the union that represents workers at City of Palo Alto, noted local contractors are having difficulties finding engineering and construction workers for projects.

And even if there is not a shortage of workers for a particular field, such as entry-level utility jobs, “the problem is that these people have no lives,” Krug said. “These people have no lives. The utility workers are commuting over an hour each way.”

“When do you see your family?” Krug asked. “It’s a privilege to live here but it’s not going to be a privilege when you don’t have any service workers, when you don’t have people that can respond to emergencies.”

As Krug notes, the issue of essential workers living far away extends beyond long commutes. Rep. Jackie Speier (D-14) said in a recent interview with Peninsula Press that “we have law enforcement and first responders who are living in trailers in the parking lots of city halls because they can’t afford to live here anymore.”

“So when the big earthquake does hit us,” Speier said, “where are our first responders going to be? Not here.”