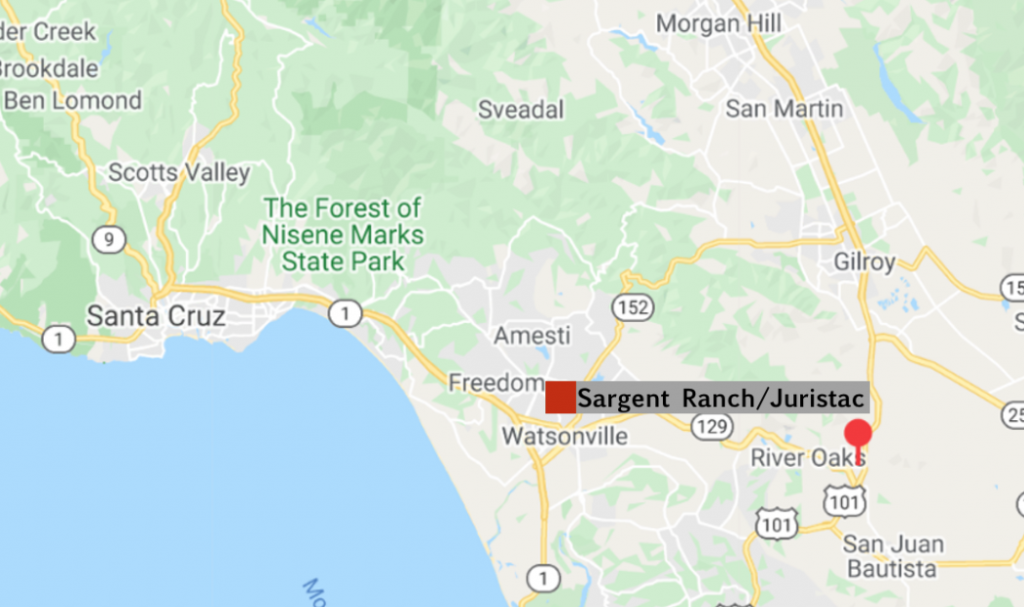

Just south of Gilroy, a contentious 6,400-acre piece of land has a different name depending on who you ask. To local tribe the Amah Mutsun, it’s Juristac — a sacred ritual site. To most neighbors, it’s Sargent Ranch. To the Debt Acquisition Company of America — the investment company that gained control of the land in 2013 — it’s Sargent Quarry, the site of a proposed sand and gravel mining operation.

The Debt Acquisition Company of America, or DACA, argues the project generates a rare, more environmentally sustainable avenue to sand — a necessary ingredient for aggregate material that fuels all Bay Area construction. The Amah Mutsun tribal leaders strongly oppose any destruction of their sacred land. Tribal Chairman Valentin Lopez says that the land was home to prayers for renewal, healing and coming-of-age ceremonies. Juristac translates to “place of the Big Head” — there, sacred gatherings drew in neighboring tribes for thousands of years.

The contention has been described in many publications as a “local Standing Rock,” referencing the activism surrounding the Dakota Access Pipeline route through Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota.

The investors see it as an environmental win because approximately 320 out of 6,400 acres on the property would be developed and the rest, about 95% of the land, would be conserved.

However, Lopez says, “The area where the mining is to occur impacts the ceremony site. And it’s going to remove four mountains, four sacred mountains, and turn them into a big pit in the ground.”

Many local environmentalist groups oppose the project since the quarry would intersect a wildlife corridor, which is vital for native species migration patterns.

To signal local opposition to the sand quarry, Morgan Hill City Council on Jan. 15 unanimously passed a resolution to support the preservation of all 6,403 acres, thus siding with the Amah Mutsun and taking a stand against any future development propositions on the land. Their resolution is a symbolic showing of support, not a change-making decision. The hope is to influence Santa Clara County’s decision when the time comes.

Sidebar: Tribal Chairman Valentin Lopez’s perspective (Megan Calfas/Peninsula Press)

Where the proposal stands now

The San Diego-based investment company Debt Acquisition Company of America gained control over the land’s development rights by helping the property transition from bankruptcy to foreclosure after its former owners, Sargent Ranch LLC, put it up for auction. In 2016, DACA proposed a sand and gravel mining quarry on approximately 320 acres of the land for the next 30 years. There is a plan to work towards restoring the land once the project is completed.

Now, Santa Clara County staffers are in the process of completing the draft Environmental Impact Report for DACA’s proposal. Once finished, it will be released for public comment, edited as needed, then sent to the planning commission for approval.

The report has been delayed for months. It is due to come out early this year, according to Santa Clara County, though some believe it might not be ready until summer. The delay is the result of the county being required to measure not only potential ecological impacts but also cultural impacts to indigenous tribes in the area. It’s one of the first times that the county is performing such a review.

This is Assembly Bill 52 in action. Governor Jerry Brown signed it into law in 2014, expanding the considered categories of “environmental resources” under the California Environmental Quality Act to include “tribal cultural resources.” Officially implemented in 2016, it allows tribes to consult on projects proposed on their historic land.

“It’s a whole new world that we had never dealt with,” said Rob Eastwood, Santa Clara County planning manager.

The bill was considered a big win for the indigenous community because it “allows for the tribe to be at the table at the earliest point possible,” according to Merri Lopez-Keifer, chief legal counsel for the San Luis Rey Band of Mission Indians.

Before AB 52, tribes would often not hear about projects that impacted their historic land until the process was too far along for changes to be possible.

Eastwood says the intent was to take into account the fact that “there are landscapes that are important to tribes that have emotional, spiritual significance.”

Lopez-Keifer emphasizes this, saying, “For the California native, this is our spiritual place. These are our sacred places, our churches.”

The Amah Mutsun requested an AB 52 process for the Sargent Quarry proposition. As part of that process, the county hired an ethnographer to document oral histories of the tribe and their involvement in the area. Summaries of these findings will be published in the upcoming draft Environmental Impact Report.

Once the Environmental Impact Report is released, there will be a 60-day period for public comment. The Amah Mutsun have collected nearly 11,000 signatures opposing the project and are hopeful that much of their support will translate into public comments, because in Lopez’s eyes, “public comments are really the only things that will turn this around.” At the Morgan Hill City Council meeting, supporters of the tribe delivered an hour of public comments collectively.

Eastwood’s department is expecting a flurry of comments as well. They have over 1,900 people on the project’s “interested parties” email list — an unprecedented number for “a remote proposed quarry in a part of the county where not that many people live,” he says. The county’s department is required to respond individually to each public comment, which slows the process.

Howard Justus, director of DACA, says that the public should “caution before rushing to judgment” until the Environmental Impact Report is released and its facts are made public.

If the project is approved as is, the Amah Mutsun (or anyone) could appeal the decision and take the case to court under AB 52.

Since the law passed, no completed cases have appealed and challenged AB 52’s requirements or implementation. And, since the AB 52 process has been started, the agency running the project must incorporate “culturally appropriate mitigation measures,” according to Lopez-Keifer.

This requires developers to address the negative impacts on tribal cultural resources, even if the project is approved to move forward. These measures can take many forms, including oral histories and tribal-led ethnographic studies. Lopez-Keifer says, “it’s about preserving the legacy of our ancestors for future generations.”

Lopez and Justus expect differing results as they await the environmental impact report’s release. Justus anticipates, “the environmental impact report has […] uncovered very little Native American involvement with the Ranch.”

Lopez says, “I believe it’s going to show greatly in our favor that Juristac is an important spiritual and cultural site to the Amah Mutsun.”

Amah Mutsun leaders have organized activist efforts in opposition to the quarry — they’ve collected signatures, held a 5-mile, 400-person march on Sept. 8 outside the land, and most recently, rallied over 100 people to Morgan Hill City Council. They filled the council chambers and shook homemade signs bearing slogans like “Protect Sacred Land” to quietly applaud the proceedings. Once the “ayes” were spoken, the room erupted into cheers.

At the Morgan Hill meeting, representatives from the Committee for Green Foothills and the ACLU of Northern California, among others, came to voice their opposition.

The sand debate

Supporters of the quarry believe it’s a necessary avenue towards a high demand resource. Sand is a big deal. There is a global sand crisis underway since it’s an essential ingredient for construction, and most areas are depleting their local resources. In the Bay Area, sand has been imported for a long time, often from Canada on barges or Southern California on trucks.

Out of the nine current quarries in Santa Clara County, none of them process sand, leading to a “big deficiency in sand resources,” according to Eastwood. And on top of that, Sargent Ranch offers unique sand — it can be taken from a hillside, rather than where it’s usually found, in creeks or streams, avoiding a more environmentally invasive extraction.

In a 2018 report, the California Department of Conservation notes that projects like Sargent Quarry are “often seen as controversial land use during the permitting process” but that environmentally and financially “there are benefits to local sources” of sand for construction.

Vince Beiser, author of The World in a Grain, a 2018 book about the history of sand, noted that at the end of the day, the sand has to come from somewhere.

“People don’t realize that if you say, ‘not in my backyard,’ you’re really just pushing that problem into somebody else’s backyard,” Beiser said. And often, the projects get pushed to the most vulnerable neighborhoods. “The sand mining companies then just have to go somewhere where there’s communities with fewer resources who aren’t ready to mobilize in the same way.”

There are some negative environmental impacts either way — with imported sand, trucks bring higher carbon dioxide emissions. With the local sand from Sargent Quarry, there’s a threat to native species who use that wildlife corridor.

But the big question remains on how the county will factor in tribal cultural loss alongside these ecological impacts.

And so Morgan Hill marks the first city to declare its support of preserving all 6,403 acres. Next up, the city of Santa Cruz will consider a similar resolution of support — it’s on their agenda for Feb. 11. But no formal decisions can be made until Santa Clara County completes the AB 52 process and releases the draft Environmental Impact Report.