Over the last four years nearly 500 companies have reported data breaches under California’s data breach notification law — each one affecting a minimum of 500 people and some affecting thousands.

As Stanford University readies for a visit from President Obama Friday — where he will speak at the White House Summit on Cybersecurity and Consumer Protection — some experts worry that California law requiring reports on breaches will be weakened by the president’s push for a national standard.

Companies around the nation are already following state laws that are far stronger than a new federal law that Obama is proposing. Under the president’s proposal, companies could skip notifying customers whose information has been breached if they conclude that “there is no reasonable risk of harm or fraud to such individual.” This clause, which experts say could be abused by companies, isn’t present in California law.

Security experts like Jonathan Mayer — a Ph.D. candidate in computer science at Stanford University whose research focuses on technology policy — are frustrated by the regressive nature of proposed policy changes and aren’t holding out hope for Obama to make any surprise announcements at the summit.

“In an ideal world [Obama would] say we’re not going to preempt good state data breach notification law and we’re not going to immunize private businesses when they share data with the government,” Mayer said in a phone interview. “But unfortunately that’s probably not what’s going to happen.”

Obama is expected to discuss tighter data-handling standards and to unveil the administration’s plan to expand efforts to facilitate cybersecurity information sharing between the private sector and Department of Homeland Security. According to The White House website, topics of discussion at the summit will also include finding more secure payment methods, cybersecurity information sharing, international law enforcement cooperation on cybersecurity and new ideas on technical security.

Following the recent spurt of high-profile hacks, dealing with cybercrime has become a priority for the Obama administration. In his State of the Union address, Obama called for a more uniform federal cybersecurity law.

But security experts are concerned that the implementation of a uniform federal standard may hinder the fight to prevent breaches, by creating less of an information flow, especially in California, which has one of the strongest breach laws in the country.

“President Obama [has] outlined a proposal that would require companies to inform their customers of a data breach within 30 days of discovering their information has been hacked,” investigative reporter Brian Krebs wrote on his website, KrebsonSecurity.com. “But depending on what is put in and left out of any implementing legislation, the effort could well lead to more voluminous but less useful disclosure.”

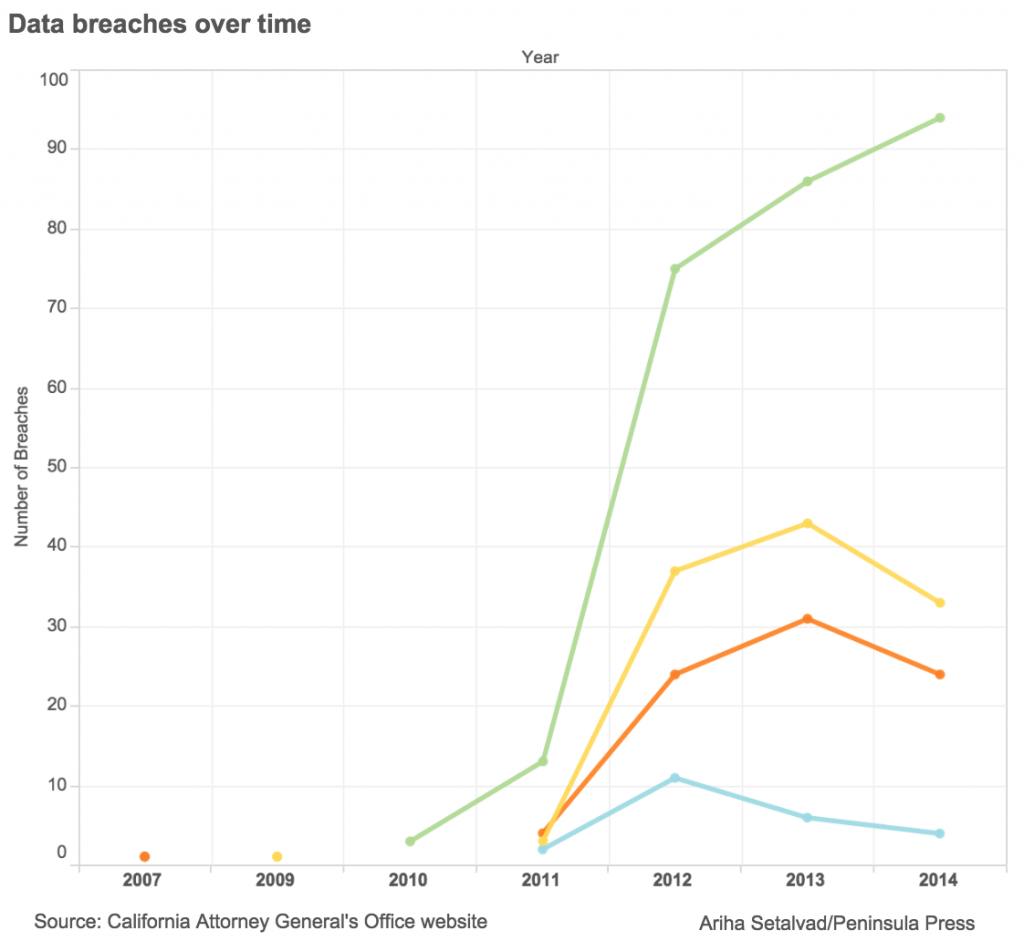

As of 2012, companies and government agencies subject to California law have been required to submit copies of their data breach notices to the Attorney General if the breach involves more than 500 Californians. In one year alone, more than 130 data breaches were reported, and that number of overall breaches has continued to increase.

The data reported to the Attorney General’s office includes reports from 2011 because some companies were hacked in 2011 but reported it to the state in 2012 when they realized it. It also shows that while malware breaches are still increasing, data breaches due to negligence (thefts or errors) and other types of breaches all declined in 2014.

Still, of the data breaches reported under California law from 2011 through 2014, nearly half were due to either “physical theft or loss,” defined by the California Attorney General’s Office as “unencrypted data stored on laptop, thumb drive or other device removed from owner’s control” or “errors,” defined as “anything unintentionally done or left undone that exposes data to unauthorized individuals.”

This calls attention to one of the greatest concerns in cybersecurity policy, that most organizations rely on automated systems, such as office computers, which are increasingly vulnerable for surprisingly simple reasons; they have a default password or do not have the basic protections enabled to prevent them from being accessed via the Internet.

For example, Cedars-Sinai Health System, a hospital in Los Angeles, reported in 2014 that an employee took a Cedars-Sinai issued laptop home and had it stolen. The laptop contained certain patient information, but the hospital was unable to confirm exactly what information was on the laptop.

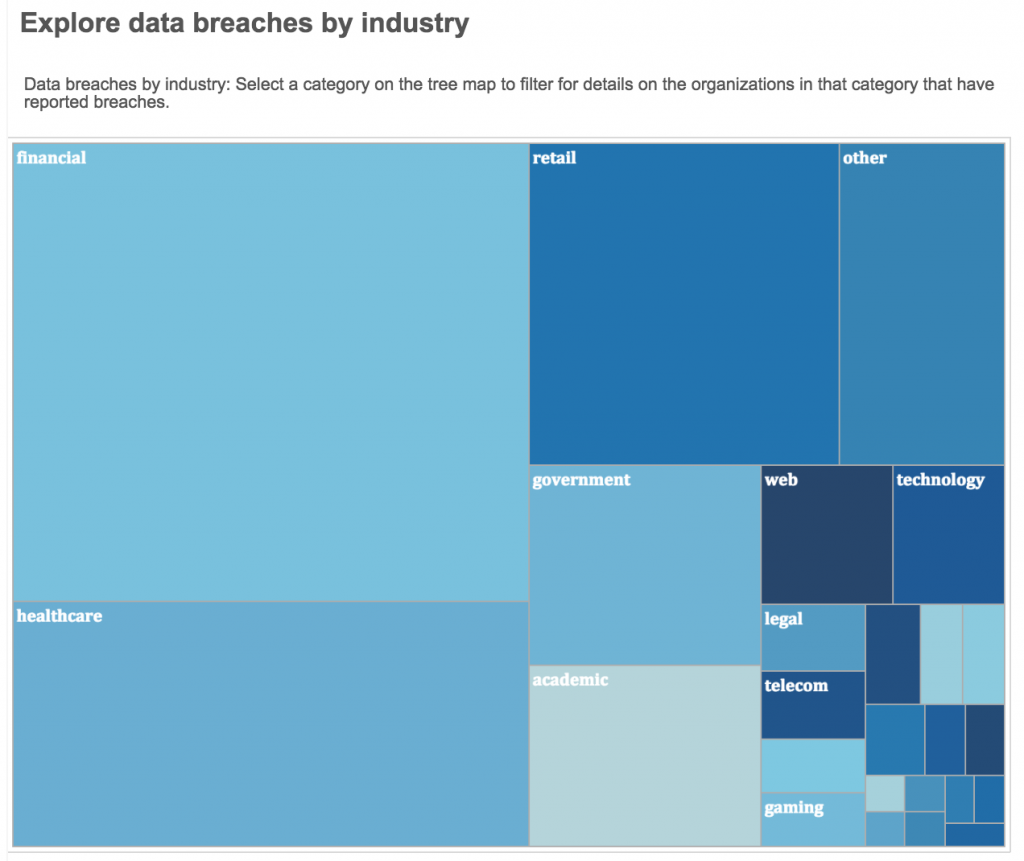

Organizations responsible for some of our most sensitive information — such as financial organizations, hospitals and healthcare facilities, and government organizations — have seen the largest number of breaches, based on the data reported to the State Attorney General.

A large number of breaches could be prevented by simple due diligence, such as regular security audits or basic training for employees, Mayer said.

“Companies are tripping over themselves to collect oodles of potentially very sensitive such data from consumers, and yet we still have no basic principles that say what companies can do with that information, how much they can collect, how they can collect it or share it, or how they will protect that information,” Krebs wrote on his website.

“Overall, we’re really lacking any sort of basic protections for that information, and consumers are giving it away every day without fully realizing there are basically zero federal standards for what can or should be done,” he added.

Homepage image courtesy of Twechie on Flickr via Creative Commons.