With a wingspan that can reach up to 10 feet and an array of stark black feathers, the California condor is hard to miss against the neon blue California sky — if you’re lucky enough to spot one.

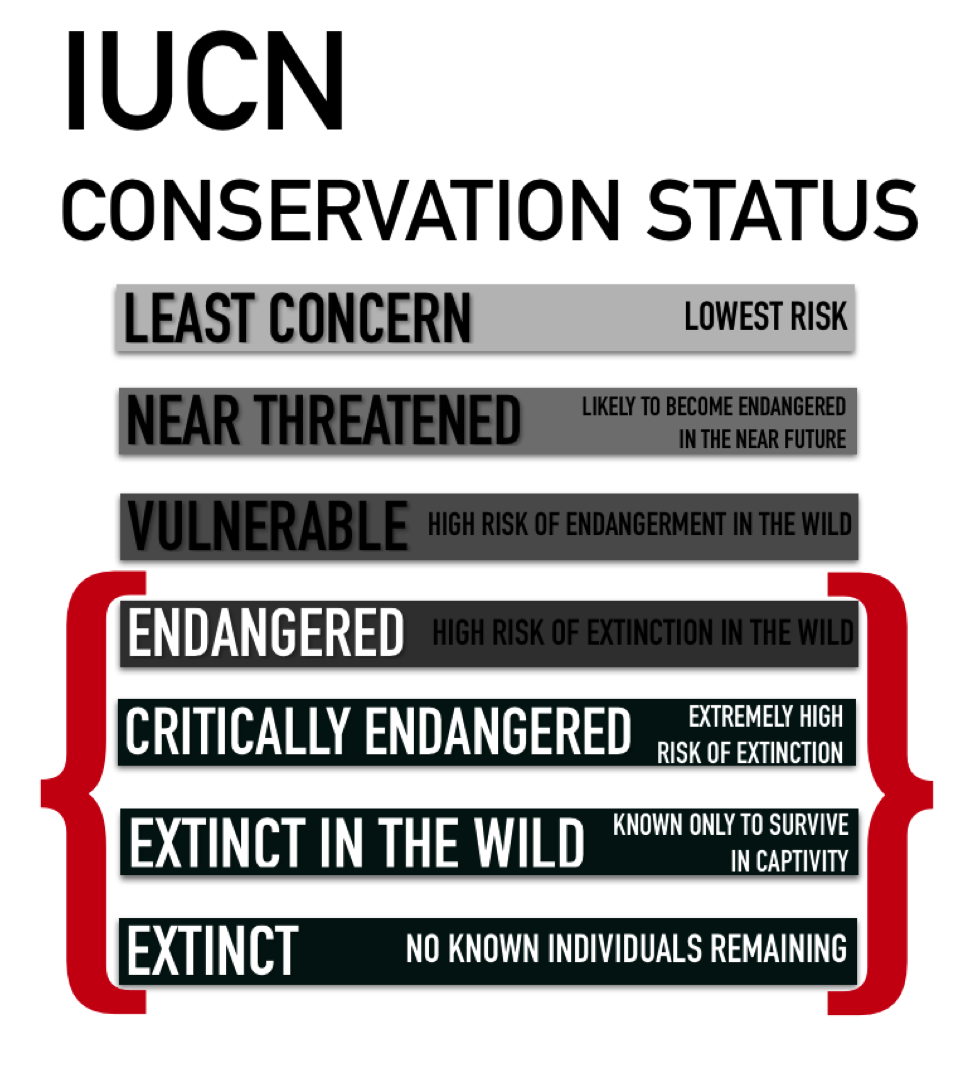

The critically endangered species is one of the rarest birds in the world, but just this winter, scientists were surprised by the sighting of an untagged young fledgling.

“It’s exciting because it demonstrates that the birds can do it on their own,” said Steve Kirkland, California condor field coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). “It’s encouraging.”

After becoming extinct in the wild in 1987 when all but 22 captive birds had died out, a conservation plan was initiated by the USFWS. Now, with just above 200 known wild birds, the species’ status has been changed to critically endangered.

Every known egg, chick and adult is carefully tagged and tracked its entire life, which can reach up to 60 years. Additionally, mortality rates and causes are analyzed in order to determine deterrents to population growth, said Rachel Wolstenholme of Pinnacles National Park.

While the unexpecting fledgling was a small victory for the species, recovery for the condor is a slow process. Kirkland added that one of the major challenges in recovery is lead poisoning.

“The problem is that most of the food condors are finding is contaminated with spent lead ammunition,” Kirkland said. “The story with condor recovery, or lack thereof, is lead poisoning, not habitat loss. More birds die of lead poisoning than are produced in the wild.”

Fortunately for the condor, part of the Ridley-Tree Condor Preservation Act of 2008 makes the use of lead ammunition illegal within certain boundaries. These boundaries coincide with the condor’s wild habitat range.

A significant portion of birds are still found with symptoms of lead poisoning, according to the condor status report from October 2014 and studies by researchers at UC Santa Cruz.

The act only restricts the use of lead ammunition in big game hunting, Kirkland said. This means hunters and land-owners can still use lead ammunition for things like livestock management and nuisance animals. When animals are shot but not killed, they can take traces of lead back into the ecosystem, which in turn, can end up harming the predators that subsist on them.

“More birds die than are put back into the population, without us supplementing it, and the number-one cause is lead poisoning,” Kirkland said. He added that as the condor’s range continues to grow beyond the lead-banned area, risk of exposure increases. “It’s sort of a catch-22 in a way.”

The map below illustrates how some condors are straying far from release sites (like Pinnacles National Park) and into unrestricted areas. Exact locations of GPS tagged cannot be published to protect the birds’ safety.

“We want hunting to occur; for us it’s a necessary part of recovery,” Kirkland said. “Humans are part of the landscape here.”

Wolstenholme echoed this sentiment by pointing out that the key to finding harmony between species recovery and hunters is education.

New legislation that would restrict lead ammunition in the condor’s habitat is set to go into effect in 2019. The law, AB 711, would maintain existing restrictions, but would also put a complete ban on lead ammunition for hunting.

But scientists and conservationists alike don’t expect this to mean an immediate recovery.

“We’re basically in a waiting game as to whether or not we can build self-sustaining populations,” Kirkland said. “And we’re not near self-sustaining yet because of the lead issue.”

A timeline of the major events since the bird almost met its fate:

(Data source: California Department of Fish and Wildlife.)

(Homepage photo courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service/Gary Kramer)