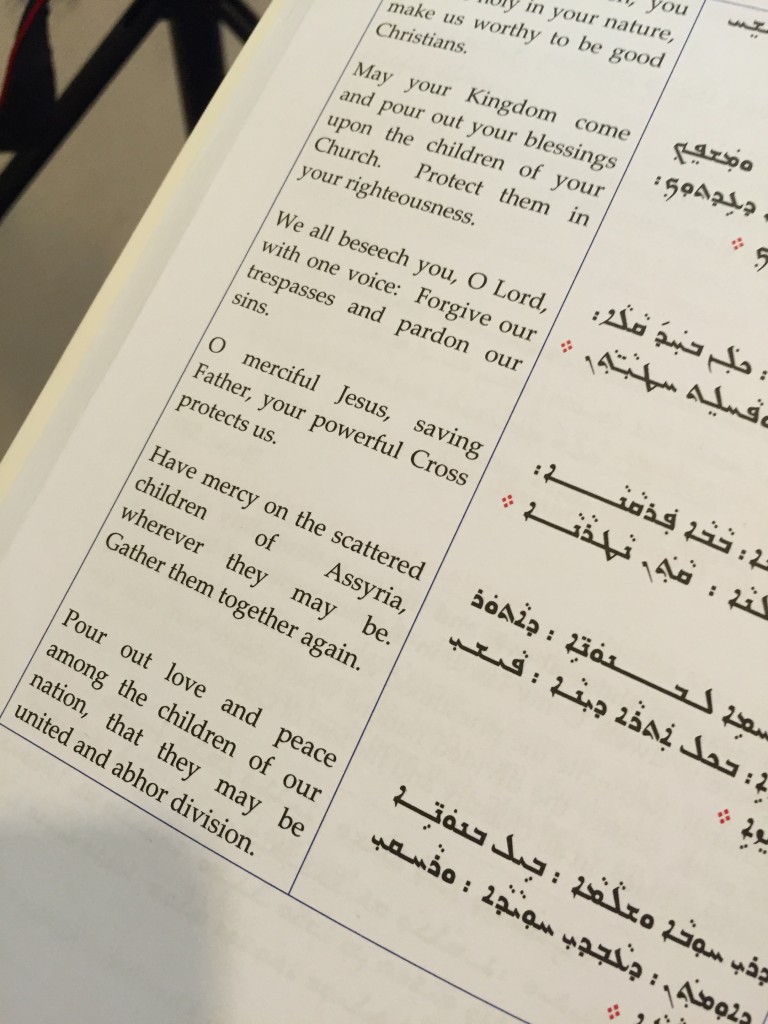

On a recent Sunday morning inside Mar Yosip Assyrian Church of the East in San Jose, sunbeams slant through clouds of incense smoke onto the face of Father Lawrance Namato as he leads his congregation in a liturgy nearly 2,000 years old. The suited men and veiled women in the pews — nearly all of them Assyrian — join in the ancient chants as they pray for peace and resolution to a crisis both historic and modern: the persecution of their brothers and sisters in the Middle East.

Indigenous to northern Iraq, Assyrians have lived in the region for more than 6,000 years. They converted as a people to Christianity in the first century A.D. and are one of the oldest continuous Christian communities in the world. But in the past century, violence and religious persecution have escalated, forcing most of them to seek safety in other countries. Some 10,000 now reside in the Bay Area. With the rise of the Islamic State, they now risk vanishing from their homeland altogether.

The problem is that “the Christians have nowhere to go,” said Father Lawrance, whose family fled Kirkuk, Iraq, when he was 14 as former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein rose to power.

Most of the parishioners at Mar Yosip are from Iraq or Iran, although a few are from Syria and other countries in the Middle East. Many in the community still have family in the Middle East: some who have remained by choice, others who are caught in the limbo of refugee camps as they await a chance at a new life.

Since the rise of the Islamic State, Assyrians in the Bay Area have tried multiple avenues to help their relatives in the region. Some have petitioned the State Department to more forcefully defend Christians in the Middle East. Others are urging the United States Agency for International Development to directly fund Assyrian humanitarian aid groups. And others are working to get families approved for asylum in the United States.

But many in the community feel disappointed so far in the U.S. response. And there is a deep worry that this ancient group could disappear completely.

“We kind of feel like our life is paralyzed,” said Rochelle Yousefian, president of the Assyrian American Association of San Jose. “The government that we are so proud of living in in the country of peace is not taking any actions, it’s not even open to listen to these atrocities. It makes us feel hopeless; it makes us unproductive because we don’t know what to do, we don’t know how to help.”

The history of Assyrian Christians in the Middle East has been punctuated by periods of violent persecution. In 1915, the year Assyrians call the Seyfo — “the year of the sword” — the Ottoman Empire slaughtered as many as 300,000 Assyrians. In 2003, it was estimated that 30,000 Assyrian Christians still lived in the city of Mosul in northern Iraq. But after the Islamic State captured the city in the summer of 2014, none remain — having been either killed or forced to flee.

“This is a genocide,” said Albert Nissan, a Mar Yosip parishioner who emigrated from Baghdad in 1975 and has family members still living there.

“The people who emptied Mosul of its Christians are the same people who bombed Paris,” he added, referring to the November attacks by Islamic extremists that killed 130 people and injured hundreds more.

No safety in Syria

When the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, many Assyrians sought refuge in Syria, which was comparably peaceful at the time. But they were held in UN refugee camps “for years,” said Father Lawrance, and when civil war broke out in Syria five years ago, some were trapped again by the violence they had hoped to escape.

Conditions for Assyrians in Syrian refugee camps are “horrible,” said Poline Maiel, a parishioner of Mar Yosip. Girls risk being kidnapped and Christians are frequently targets of violence, she said. “Whatever we think about [Syrian President Bashar al-] Assad, before the war the Assyrians [in Syria] had a good life and they were safe. Now, they are targeted by everybody.”

In February, the Islamic State captured around 230 Assyrian Christians in Syria and held them for a ransom of around $14 million. That month, Assyrian Bishops in the United States called on Secretary of State John Kerry to take “concrete steps to help the remaining Assyrian Christians in the region to protect themselves.” The Islamic State released some of the sick and elderly prisoners, but continues to hold around 150 Assyrian Christian hostages.

In October, three of the hostages were executed. One of the victims was the first cousin of a parishioner at Mar Yosip, and other family members are still being held for ransom by the Islamic State.

Asylum at last

In June 2014, Shamiran left her village outside of Mosul with her three teenage children on temporary visitor visas to attend a family wedding and visit her parents in the Bay Area, who are parishioners at Mar Yosip. But when ISIS overtook Mosul that summer, her husband who had remained in Iraq told her not to return because of the security risk.

Unable to return to Iraq, “Shamiran” — who didn’t want her real name used because of security concerns — and her children applied for asylum in the United States. In June, nearly a year after their arrival, they were granted asylum.

In broken English, Shamiran described the experience of Christians in Mosul who were forced to flee the city and have their houses marked as being inhabited by Christians. “There were many Christian families in Mosul,” she said. “They left everything in Mosul and they went. [ISIS] put Arabic letter “Nun” [on our houses]. It means Christian — “Nazarene.”

Shamiran’s husband’s request for asylum has also been approved, but he’s still waiting for the U.S. embassy in Baghdad to certify his identity and complete a background check.

Having been in the United States for a year-and-a-half now, Shamiran has found a job working at a grocery store, and her three children are earning A’s in Bay Area high schools. But she yearns for the day when she can be reunited with her husband. “My husband is safe now, thank God. I need for him to come here to live in peace with us to be a family again.”

Waiting for visas

For the few Assyrian Christians left in the Middle East, the threat of attacks by the Islamic State makes each day more perilous. But migrating to the West has become increasingly difficult, as waves of refugees from the Middle East and North Africa pour into Europe. In the United States, fears of terrorism have prompted debates about how many — if any — refugees the United States should admit.

Father Lawrance agrees that refugees to the United States should be screened carefully to prevent terrorists from being admitted to the country. “But they have to differentiate between who’s doing the killing and who’s being persecuted,” he said.

Rep. Anna Eshoo, the only Assyrian member of Congress, serves California’s 18th district covering parts of San Mateo, Santa Clara and Santa Cruz Counties. Eshoo, a Democrat whose parents are Assyrian Christians who fled persecution in the Middle East, voted in November against a House Republican bill to pause the admittance of Syrian refugees into the United States. Despite its passage by a wide majority that included many Democratic votes, Eshoo voted against the measure because it amounted to a “bureaucratic blockade for all refugee applicants.”

In June, Eshoo, who is the co-chair of the Religious Minorities in the Middle East Caucus, called on President Barack Obama to do more to help Middle Eastern religious minorities like Assyrians by prioritizing additional security support for vulnerable populations, especially the ancient Christian community. Eshoo has also called on the president to designate an additional 5,000 priority refugee visas for religious minorities from the Middle East.

But the process, said Eshoo in a recent interview, is “very, very slow,” since the United States has a complex system of rules for granting refugee visas. Eshoo says her goal is to expedite visas for Middle East Christians, since she fears that relief might not arrive before they are “dead and gone.”