Just off of Highway 101 in Redwood City on Seaport Boulevard, a truck carrying stacks of old flattened cars rumbles eastward, toward the San Francisco Bay. Moments later, a different truck lugs a covered mound of dirt debris in the opposite direction.

The eastbound truck is delivering discarded vehicles to a Sims Metal Management facility, a regional branch of a multinational metal recycling company that operates a 13-acre plant at the Port of Redwood City. Sims purchases common metal waste like cars, kitchen appliances and crop irrigation pipes, feeds them into a metal shredder and then ships the fist-sized scraps overseas to sell for manufacturing.

The truck exiting Sims is disposing of non-metal shredder residue, en route to a private landfill far outside county lines. This residue looks like dirt, but is really a blend of plastics, rubber and fabrics that are coated with fine bits of metal from the shredding process.

These two vehicles represent the input and output of an intricate metal recycling operation.

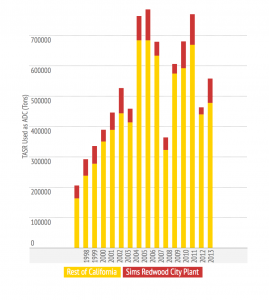

Metal recyclers in California export more than seven million tons of metal annually. The two metal shredders currently operating in the Bay Area — Sims in Redwood City and its competitor, Schnitzer Steel in Oakland — contribute around 600,000 tons a year.

While metal recyclers provide benefits to society by conserving resources and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, the toxic nature of the materials being handled poses a dilemma for the industry and its regulators. When not contained properly, metals such as lead, mercury, copper, zinc and cadmium can have serious health effects for people and wildlife. The industry’s method of managing the risks associated with these metals is under close scrutiny today.

There are more than four different agencies responsible for ensuring that metal recyclers abide by a series of regulations in the Bay Area, including the Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Toxic Substances Control, San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board and the Bay Area Air Quality Management District.

Despite the number of organizations which oversee the industry, problems with regulation abound. In the past two years, regulators have collectively fined Sims millions of dollars for violating various state and federal laws at its Redwood City plant. The records behind these fines describe years or even decades of violations and illustrate a broader story about the difficulty of regulating the metal shredding industry.

This year, a new law spearheaded by state Sen. Jerry Hill (D-San Mateo) may push more stringent regulation for parts of the metal shredding process, though some environmental advocates question how effective the law will be.

Officials from Sims Metal Management declined to be interviewed in detail for this story. Jill Rodby, Sims’ public relations and government affairs manager, pointed the authors to public statements made at the time regarding specific settlements or fines. In general, these statements convey that the company intends to comply with the relevant regulations moving forward. Rodby also provided information about the timeline of improvements being made to the Redwood City facility.

Timeline: A history of metal recycling regulations and violations at Sims in Redwood City

Fires at Sims draw attention to recycling industry

The Sims plant drew attention from local residents in late 2013, when two fires broke out at the facility in less than two months and engulfed the Peninsula in noxious black smoke. Redwood City issued shelter-in-place warnings during the first fire on Nov. 10 and advised citizens to stay indoors and close air intake systems during the second fire, which occurred just over five weeks later.

Sims’ experiences with fires aren’t unique, said Redwood City Fire Marshal Jim Palisi.

“Unfortunately, with any kind of recycling business, you are going to have a threat of a fire,” Palisi said. “When you use heavy machinery to break up materials, you are going to have heating, you’re going to have friction, you’re going to have sparks.”

The Bay Area Air Quality Management District’s incident reports from both fires note that the District’s ambient air quality monitors picked up on elevated levels of fine particulates consistent with the smoke plumes, but do not further specify what particulates were found.

According to Thomas Cahill, professor emeritus of physics at UC Davis, this type of smoke may contain sharply elevated amounts of ultrafine metals, which have the potential to cause serious damage to the cardiovascular system as they accumulate in the lungs.

Cahill, whose experience with aerosol pollution spans several decades, happened to be measuring air particulates near another shredder in Oakland during the first fire. His equipment picked up the smoke emanating from the Sims facility.

“No one in the world was looking at that smoke at the time,” Cahill said. “The fact that we found it was a surprise. Clearly, the local air district did not know and we found out by accident.”

Cahill said he is not able to divulge what he found in the smoke because the results are currently being used in litigation, though not against Sims. However, he expressed concern that the regulatory agencies were not more closely monitoring the effect of these fires on air quality in the surrounding communities.

Cahill believes that the government’s regulatory standards for determining the potential harm of airborne emissions are inadequate and focus on the wrong measures of particulates.

“The typical aerosol standard is [based on] mass. But mass doesn’t hurt anybody — mass is just a measure of how much is there, not whether it’s toxic,” Cahill said. “It could be the same mass of cadmium or the same mass of sea salt. Obviously in terms of human beings, it would be an enormous degree of difference.”

Clean Water Act violations come to light

Since the early 1990s, Sims operated its ship-loading conveyor belt without adequate pollution controls to prevent materials from falling into Redwood Creek, according to a Department of Justice civil action against the company. Until the conveyor was enclosed almost two decades later, Sims allowed scrap metal and other materials to fall into the creek, according to the DOJ action.

The civil action also states that since at least November 2002 through July 9, 2012, Sims violated its General Stormwater Permit by allowing pollutants to flow into Redwood Creek and the City municipal storm sewer system every day it rained more than one tenth of an inch.

In July 2003, Sims conducted a study of the shoreline near the Redwood City Plant’s conveyor system and found that several soil samples exceeded the California Code of Regulations’ total threshold limit concentration for copper, lead, nickel and zinc. Sims declined to comment on whether the company took any action based on these findings.

According to David Wampler, an EPA Clean Water Act Enforcement Officer, the EPA did not know about this study until they launched an investigation of the facility for other violations in 2011.

In December 2011, the EPA issued an Administrative Order of Compliance ordering Sims to correct several violations of the Clean Water Act, including an inadequate Stormwater Pollution Prevention Plan and waste monitoring program.

In the same month, the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Quality Control Board conducted its first formal inspection of the plant in 11 years. The time between inspections is due in part to the sheer number of facilities that fall under the Board’s jurisdiction, said Assistant Executive Officer Thomas Mumley. “The type of investigations that have gone on at Sims are more the exception than the rule,” Mumley said. “There’s just a lot of places. Ten percent are inspected [annually] in general and probably a smaller percent are targeted for more detailed investigations.” Wampler noted a similar situation when discussing the EPA’s inspection coverage. “There are hundreds of thousands of facilities that are potential candidates for inspections across our country for Clean Water Act industrial stormwater, and choosing which ones we go to is an art and a science.”

Presence of toxic metals at Sims facility

Auto shredder ‘fluff’ found in wildlife refuge

The Sims plant is next to two other properties: Bair Island, which is part of the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge, and salt flats owned by Cargill. In early 2011, Cargill became concerned about a fluffy gray material accumulating on its property and reported the issue to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), which maintains Bair Island. According to Mendel Stewart, the manager of the refuge at the time, the FWS contacted Sims about the material and discovered that it was light fibrous material, also known as auto shredder residue. Light fibrous material is a byproduct of the metal shredding process and is comprised of non-metal materials that go through the shredder, such as rubber and auto fuel. It can contain levels of metals that exceed the regulatory thresholds, as well as potentially toxic chemical compounds such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). The FWS tested the wetlands of Bair Island and found elevated levels of metals and trace levels of PCBs and phthalates.

In May 2011, the FWS notified Sims of its concerns. Representatives from the FWS later visited the Sims facility in September 2011 and spoke with Marc Madden, who was previously Sims’ regional director of government relations. By December 2011, the company had not taken action to resolve the issue, according to a letter from the FWS to Sims and several regulatory agencies, including the EPA.

Sims responded to the complaints by modifying the Redwood City facility layout, installing a large overhead sprinkler system and using water trucks to keep down dust, according to a March 2013 report from the FWS. The FWS could not find records of exactly when the upgrades were made, and Sims declined to comment on this issue.

However, Sims continued to allow light fibrous material to be released from the plant, according to a civil environmental enforcement action that the DTSC filed against the company in November 2014. Sims settled the case for $2.4 million on the day the action was filed, but admitted no wrongdoing. As part of the settlement, Sims was required to make several capital improvements to the facility, such as fully enclosing the metal shredder, by June 30, 2015. Sims has completed several upgrades and received an extension for some other work, “primarily completion of the shredder enclosure, for which work has already begun,” Rodby said in an email.

The company was allowed to request the extension based on a showing of good cause, Rodby said in the email.

(Source: CalRecycle | Chart Tool: Infogr.am)

New law seeks to address weak regulations

A new state law authored by Sen. Jerry Hill addresses some of the issues with regulating metal shredders, particularly the classification and regulation of auto shredder residue.

It was the 2013 fires at Sims that first drew Hill’s attention to metal shredding regulation. Hill, who represents the San Francisco Peninsula, said that after further investigation, he concluded that the industry’s regulators were largely ineffective.

“I found that basically the [metal recycling] industry has not been regulated,” Hill said. “[Regulators] have been trying to regulate it since the 1980s. I felt there was some legislation necessary.”

The new law, which took effect January 1, 2015, requires the Department of Toxic Substances Control to reconsider its decision to exempt many metal shredders from the regulation that classifies “treated” auto shredder residue as non-hazardous. The light fibrous material that concerned the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service is a non-treated form of auto shredder residue.

The shredder waste treatment process is supposed to reduce the amount of metals and chemical compounds to below the regulatory threshold for hazardous materials. However, a 2002 study by DTSC Senior Scientist Peter Wood found the treatment was often inadequate. The study, which was published in draft form but never officially finalized, stated that all of the samples of treated auto shredder residue collected from California shredders still contained hazardous levels of metals.

While this material is sitting in landfills, these metals may seep into the ground and contaminate nearby stormwater.

“The [treatment] is there to stabilize ASR [auto shredder residue] for handling and transport,” said Len Keck, project manager and owner’s representative at Westfield Consulting L.L.C., a firm that advises recycling companies. “Once it gets to the landfill, there’s a lot of theoretical debate over whether or not that helps or doesn’t help.”

Under the new law, the hazardous waste exemptions will expire on January 1, 2018. But whether that will lead to new regulations is still an open question. The DTSC can choose to maintain current standards for auto shredder residue if its analysis proves that these standards do not pose a significant potential hazard to human health or the environment.

Despite the legislative action, industry followers are dubious of the DTSC’s ability to improve its decades-old policies regarding auto shredder residue.

“I’m always skeptical,” Hill said. “Especially with the DTSC because historically they have not acted, I believe, responsibly in their oversight of facilities like this.”

Keck also questioned whether or not the DTSC would be able to successfully regulate auto shredder residue, even though this new law gives the agency more authority.

“Ever since the 1990s, the DTSC has wanted to regulate it [auto shredder residue],” Keck said. “And it is always going to be next year, or six months from now. I don’t know if this is real, or if this is one more effort at marching in place.”

How we investigated this story:

To examine the issue of metal recycling regulation, a team of three Stanford students reviewed inspection data and legal records from five different government agencies, including the Environmental Protection Agency, the San Francisco Regional Water Quality Control Board, the Department of Toxic Substances, the Bay Area Air Quality Management District and the San Francisco District Attorney. Outside environmental and industry experts helped reporters interpret the data and documents and provided commentary about the state of the metal recycling regulation system. Some of the records were available on the web, while others required public records requests. The measurements of metal levels near Sims Metal Management in Redwood City were obtained from facility inspection reports conducted by the Environmental Protection Agency and the San Francisco Water Quality Control Board.