Armies of trolls are bombarding Bay Area activists on Facebook through disinformation campaigns and online harassment. But Facebook’s response to two attacks has left the activists feeling frustrated and confused.

Adrian Bonifacio is a recent Stanford graduate and a human rights activist who lives in San Jose and works in San Francisco. Although a designer by trade, he spends much of his free time volunteering with Anakbayan, a Bay Area, grassroots organization that aims to reduce state-sponsored violence in the Philippines.

Currently, the Philippine’s president, Rodrigo Duterte, is under UN investigation for his brutal war on drugs, which has left more than 27,000 people dead, according to the Philippines Human Rights Commission.

Duterte’s infamy extends to his weaponization of Facebook, which he uses to spread disinformation and to attack political opponents.

His “keyboard army” (a term popularized during his presidential campaign) is comprised of automated bots and real people, some of whom are paid, while others strike on their own volition.

The attacks — which range from proliferating fake news to doxing (publicizing a person’s identifying information, generally with malicious intent) — are designed to intimidate political dissidents and create a mirage of unrivaled support for the president.

“They use exponential attacks as weapons against narratives that the government doesn’t like — like extrajudicial killings — anyone that brings them up would be pummeled and pummeled repeatedly” said award-winning Filipino Journalist Maria Ressa. “The goal of political trolling is to intimidate and to silence.”

Facebook’s problems with international disinformation campaigns are not unique to the Philippines. China uses the platform to discredit protesters in Hong Kong and an Israeli social media company coordinated attacks to influence politics in Africa and Southeast Asia. While Facebook is taking action against many of the culprits, the ubiquity of coordinated attacks shows that they don’t have the problem under control.

Trolls flood U.S.-based activists’ Facebook page

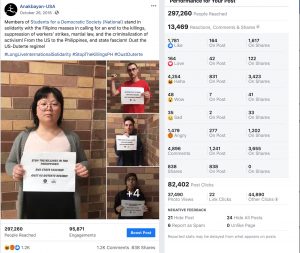

Last October, Anakbayan initiated a Facebook campaign to condemn Duterte’s war on drugs. It posted a Facebook status that included photos of college students in the United States with signs that read, “STOP THE KILLINGS IN THE PHILIPPINES” and other anti-Duterte messages.

The next day, hundreds of commenters blasted the post. The attacks ranged from insulting the activists’ appearances to claiming that they were paid actors. Some posted in English, others in Tagalog, the national language of the Philippines.

At first, Anakbayan tried to delete the comments, “but they became a flood. It was unrealistic and not worth the time to go through the 1,000-plus comments,” said Bonifacio.

Realizing that the problem was out of their control, they reported as many violating comments as they could, hoping Facebook would remove them and ban the accounts that spread disinformation and hateful rhetoric. They waited for months, but Facebook never responded to their complaint nor removed any of the comments. Nearly every anti-Duterte post that they have published since has received a similar barrage of comments from trolls and a lack of response from Facebook.

Bonifacio said some of the accounts appear to be “automated bots” (non-human users). He suspected other accounts were from “professional trolls,” paid for by the Duterte regime.

But Renee DiResta, the 2019 Mozilla Fellow in Media, Misinformation and Trust, cautioned “there is misinformation … they may be coming from the Philippines, but then to make the next leap and attribute it to the government, is a much more significant statement and requires an in-depth analysis.”

Ninety-seven percent of all people on the internet in the Philippines use Facebook, according to research by the creative agency We Are Social, and many of them use the platform to communicate with friends and family that make up some of the 10 million Filipinos living abroad.

By engaging in overseas disinformation campaigns, troll armies reinforce Duterte’s narrative from the outside in. They aim to discredit political opposition abroad by propagating a pro-Duterte narrative with expats who communicate with friends and family back in the Philippines.

“There is a market for mercenary services … trolls are often motivated by the belief that they can have an impact on the opinion of their fellow citizens, or, barring that, can harass their opposition into silence,” said DiResta.

Because trolls are frequently blocked from the platform and replenished with new accounts, there is no exact number on how many exist. However, research suggests that even a small number of bad actors can have a large reach.

In March, Facebook removed “200 Pages, Groups and accounts that engaged in coordinated inauthentic behavior…in the Philippines… Over 3.6 million accounts followed one or more of the pages that was removed,” Facebook reported.

The report also discloses the identity of the people responsible for the removed pages.

“Our investigation found that this activity was linked to a network organized by Nic Gabunada,” who is Duterte’s former Head of Social Media, the report said.

Doxing Bonifacio

In August, months after the comment attack on Anakbayan’s photo campaign, Bonifacio’s friend sent him a text to alert him that he and other activists were labeled as “terrorists” in a Facebook post that shared their photos and full names.

“It was my first time being doxxed” Bonifacio said. “I wanted the post removed because I never consented to having my information made public.”

Bonifacio reported the incident to Facebook, saying it was false. But they never responded to his complaint and never removed the post.

But after the Peninsula Press reached out to Facebook for comment on this story, the company took different actions on the Anakbayan post and the one that doxxed Bonifacio.

Facebook removed Anakbayan’s entire post (which condemned killings in the Philippines) because too many violating comments were posted to it and if left up, it would continue to attract abuse.

Facebook did not remove the post that falsely labeled Bonifacio as a terrorist and revealed his full name and photo, but did remove violating comments.

A Facebook company spokesperson said: “We take the safety of our community extremely seriously, which is why we have detailed Community Standards that outline what we don’t allow on Facebook. These standards have been developed over time with input from safety experts from around the world, and include clear policies against bullying and harassment, as well as hate speech, incitement to violence, and sharing other people’s private information. We remove this content whenever we become aware of it, and we encourage people to report content that they think breaks our rules.”

Bonifacio thinks that by removing his group’s entire message (instead of just the trolls’ violating comments) Facebook is signaling to trolls — and repressive governments — that they can silence their opponents through persistent comment attacks. “So their response was to take down the post itself, rather than addressing the hate directly?” Bonifacio said. “By deleting our post entirely, Facebook basically blamed us for “bringing” harassment onto their platform.”

Bonifacio is worried that Facebook’s response gives trolls a dangerous playbook: bombard your opponent’s message with violating comments and Facebook will have no choice but to take it down.

When asked about Facebook’s decision to not remove the post in which he was doxxed, Bonifacio responded with a brain-exploding emoji.