Rory Moroney was doing office work on a laptop at Recreation Park in Long Beach on Oct. 15, 2014, when he got up to use the park’s restroom. He was followed by a man who walked past him and smiled, which Moroney took as a sign of interest in him. The man continued to smile and give non-verbal signals of interest. But when Moroney exposed himself a few moments later, the man rushed past him and out the door, according to a lawsuit filed in Los Angeles County Superior Court.

Moroney realized what had happened a few minutes later when he exited the restroom. The man identified himself as a Long Beach police officer and arrested Moroney for lewd conduct and indecent exposure.

The charges filed against him were later thrown out by Los Angeles County Superior Court Justice Halim Dhanidina, who ruled that the arrest was unconstitutional.

“You’re hunting for gay people,” Moroney said of sting operations like the one he was arrested in. “In my case, they were parked in their four cars, four separate cars, waiting for a gay guy to enter that restroom.”

In October, four years after his arrest, Moroney settled his civil case with the Long Beach Police Department outside of court for an undisclosed amount. The same month, five men settled a class-action lawsuit related to similar sting operations of gay men in public restrooms with the San Jose Police Department for $125,000 total, which ended up being about $15,000 per plaintiff after subtracting legal fees.

At the heart of these cases is a practice that police departments throughout the state say has ended. But LGBTQ rights advocates in California say it hasn’t gone away entirely and is rooted in an insidious history of gay men being stereotyped as predators. Police departments are now feeling the repercussions of this unconstitutional practice in the form of civil lawsuits.

San Carlos-based civil rights attorney Bruce Nickerson, who represented Moroney, estimates that between 40,000 and 50,000 people in California, mainly gay men, have been arrested in illegitimate police decoy operations since 1979, the year the California Supreme Court redefined lewd conduct to include a question of whether an action was highly offensive to an observer. He arrived at that number after reading through the details of arrest reports involving decoy operations from Alameda County, Los Angeles County, San Diego County, Contra Costa County and other areas of the state.

“That’s my estimate as to how many total arrests for lewd conduct [there are] that are invalid in California,” Nickerson said.

For decades, Nickerson has argued at various levels of California courts that police decoy operations discriminate against gay men. Straight men and women are rarely if ever, targeted in undercover operations involving non-monetary sex, according to the civil rights attorney.

Nickerson has represented clients in San Jose, Mountain View, San Leandro, Manhattan Beach, Bakersfield and other California cities.

Twentieth-Century Way

The history of police sting operations targeting gay men in California goes back a hundred years. The 2010 play “ The Twentieth-Century Way” by Tom Jacobson tells the true story of two actors hired by the Long Beach Police Department in 1914 to arrest gay men in public bathrooms.

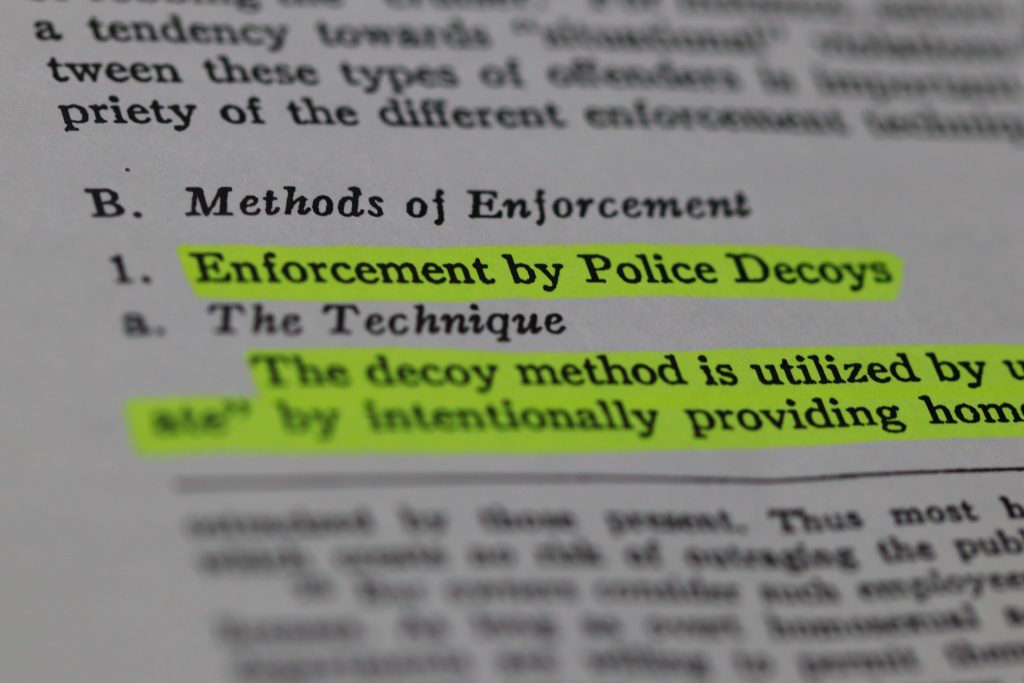

A 1966 report titled “The Consenting Adult Homosexual and the Law: An Empirical Study of Enforcement and Administration in Los Angeles County” published in the UCLA Law Review concluded that decoy operations were neither a justified nor effective practice.

“Empirical data indicates that utilization of police manpower for decoy enforcement is not justified,” the law students wrote after looking at arrest data for Los Angeles County. “It is accordingly recommended that operations of suspected homosexuals by police decoys be eliminated …”

The researchers also recommended any “dress, language or gestures employed by the decoy (officer) to indicate a desire for a homosexual relationship should be prohibited.”

Despite this research in the 1960s, the Long Beach Police Department and others continued to conduct these operations for decades.

The Long Beach Police Department declined to provide a comment or interview and referred the Peninsula Press to the department’s “Handling of Lewd Complaints” procedure. The policy was revised in 2017 to specifically state that officers investigating lewd conduct “will not engage in discriminatory practices … including [against] sexual orientation …”

Stephanie Loftin, a civil rights attorney in Long Beach who also represented Moroney, used to chair a gay and lesbian advisory group for the Long Beach Police Department. “And I probably spent 15 years there beating my head up against the wall trying to get them to pay attention to the case law with regards to the lewd conduct arrests,” Loftin said in a phone interview.

When asked whether 40,000 to 50,000 illegitimate arrests in California since 1979 seemed like an accurate estimate, Loftin said it seemed reasonable.

“I don’t think that would be an unusually high number,” said Loftin, adding that there were between 200 and 500 decoy operation arrests a year in Long Beach until recently when practice came under scrutiny.

The UCLA Law Review report found that in the one year period between May 1964 and April 1965, there were 243 decoy arrest charges filed in the Municipal Court of the Los Angeles Judicial District. In the same period, there were 2,994 total defendants charged with either lewd conduct, outraging public decency or indecent exposure.

San Jose-based family law attorney B.J. Fadem, who represented the San Jose plaintiffs alongside Nickerson and employment law attorney Lori Costanzo, said that officers used to go undercover at gay bars in Stockton, as well as areas in Alameda County known for transgender prostitution.

“When I was a police officer, these [sting operations] were going on a lot,” said Fadem, who worked as a San Jose police officer in the mid-70s.

Loftin said that some police departments in California still conduct decoy operations.

“They’re still doing it,” said Loftin, who is currently working on a case in Westminster in Orange County involving arrests of gay men for lewd conduct in adult bookstores.

Decoy operations still occur in other states as well. NBC News reported in June 2017 that the Volusia County Sheriff’s Office in Florida arrested 17 men for lewd activity in a four-day sting operation, prompting criticism from LGBTQ rights activists. Months earlier, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Police Department was sued and accused of using plain-clothed officers to target gay men at bus terminal urinals, according to The Guardian.

‘Strength for guys that needed him’

Nickerson’s first case in this area of law involved a man who was arrested by a San Jose police officer for lewd conduct while inside a booth at an adult bookstore. Nickerson got the client’s charges tossed by arguing that the man’s actions occurred in a quasi-private space and wouldn’t reasonably be expected to offend someone.

When he appeared on the O’Reilly Factor on Fox News in 2004 for a segment titled “Outrageous Ruling!,” Bill O’Reilly rebuked Nickerson for “putting perverts on the street.”

“There is, unfortunately, a long history of gays being associated with pedophilia,” said Nickerson.

In 2016, Justice Dhanidina wrote that the Long Beach police sought to “portray homosexual men as sexual deviants and pedophiles” when they arrested Moroney.

“To the extent that the Long Beach Police Department has tried to appeal to this view by gratuitously referencing school children in the reports of their lewd conduct investigations, the court rejects it wholeheartedly,” the judge wrote in his ruling.

Moroney’s voice quivers when talking about the case. “Bruce has been an amazing strength for a lot of guys that needed him,” Moroney said in a phone interview, also crediting Loftin.

Nickerson, 77, recalls a time he “probably saved a man’s life.” He said his client was arrested in Bakersfield and fired from his job as a church organist. Shortly after, he was diagnosed with AIDS and unable to afford health care.

Nickerson helped him clear his record and get his job back. “Now that is restoration,” Nickerson said.

In 1991, Nickerson was charged with helping a suspected child molester, who was one of his clients, flee the United States, the Los Angeles Times reported in 2017. Albanian police later charged the man with sexually abusing three children. When the Times brought this to Nickerson’s attention, he said he was “honestly mortified.”

Police-LGBTQ relations

In 2017, San Jose Police Chief Eddie Garcia created an LGBT liaison officer position and an LGBT community advisory board.

Additionally, Garcia implemented a policy requiring that any decoy operations be approved by the chief, LGBT liaison and community advisory board, effectively ending the practice, according to San Jose LGBT community liaison officer James Gonzales.

Around the same time, the San Jose police launched a rigorous LGBT officer recruitment campaign that Gonzales described as the first of its kind. He said they got calls from police departments “all over the country” who wanted to learn more about the campaign.

San Jose attorneys Fadem and Constanzo said they worked with the San Jose police on establishing the new policy.

“I can guarantee that while he [Garcia] is chief it will not start again,” Fadem said about decoy operations, adding that having a new policy in place helps ensure they won’t start back up under new leadership.

Reflecting on his 2014 arrest in Long Beach, Moroney says he is skeptical that prejudice in law enforcement has gone away entirely.

“Quite frankly, I don’t think that these sting operations are over as much as they say they are,” Moroney said. “I think there’s still much discrimination going on in police departments around the country.”