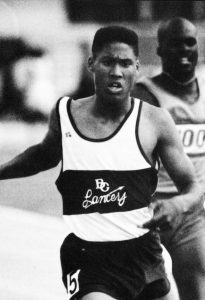

The yellow and blue triangle flags separating the track and the field were motionless — it was windless for the first time that season. And on that night at the 1996 California State Championships, Michael Granville set the national high school record in the 800 meters at 1:46.45. His winning time remains unbroken 22 years later.

The 40-year-old Granville, 6 feet and an athletic 215 pounds, currently serves as the assistant track coach at Palo Alto High School and runs his own bootcamp fitness program called “G:Fit.” He’s married with two kids, Isaiah, 10, and Noah, 7, whom he trains informally as they play water polo and run.

On the day of his record-setting performance, Friday, May 31, 1996, tumult erupted at his household. “I’m supposed to be relaxed, and now this is happening,” Granville recalls. He had just returned from an academic award banquet honoring his 3.99 GPA, among the top ranks at Bell Garden High School outside of Los Angeles. “Coming home we were a little late, and my dad’s pretty strict and punctual. It went to a whole whirlwind of chaos.”

That night, nearby Cerritos College was holding the preliminaries for the California State Track and Field Championships. Granville was the crowd favorite, having set the national freshman, sophomore and junior records in the 800m each year. He now had his sights on the overall national high school 800 meter record, set nine years before at 1:46.58.

“My younger brother, a five-year-old — he just sits right next to me and says ‘Whatever you do, can you please break that record?’ making it seem like that would make peace in the house. Being the big brother I said, ‘Okay.’”

Two laps around the oval track, or roughly half a mile, the 800-meter race is considered one of the sport’s most grueling. It is at the border between sprinting and endurance running, bringing the bulky 400-meter and lean 1600-meter runners head to head.

Granville was flustered as he arrived at the track. He had been running times of 1:48 and 1:49 that year, bogged down by the wind. But something was different about that evening. “My dad said ‘I know you’re upset and whatever. But look at the flags. The wind is not blowing. This is the night to do it.’”

His recollection of the night 22 years ago is vivid. By the time he hit the second and final lap, that’s where he felt the starting pistol go off. He began his kick at the 400 meter mark, 200 meters earlier than usual. And whether he was channeling anger at his father, demonstrating the grit earned from years of training with his father on grass fields and beaches, or trying to flee the poverty of his youth, Granville pushed harder than he ever had.

There was an eerie silence as Granville blitzed past the 600 meter mark, where his father usually stood shouting times from a stopwatch.

He wasn’t there.

* * *

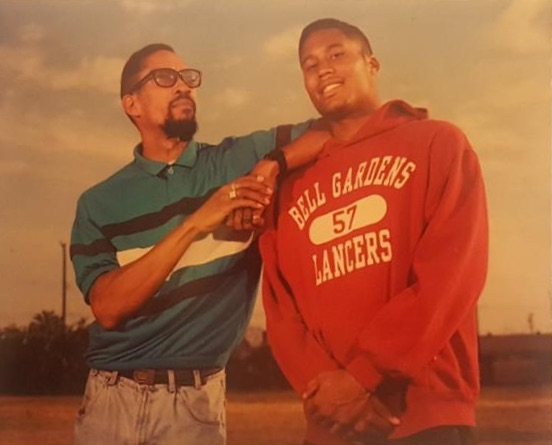

Granville’s father, Michael Granville Sr., started training his son for track from the eighth grade on. Granville Sr., an elite collegiate runner for California State University, Northridge who specialized in the now-obsolete 660 yards, was unemployed at the time. After his son proved to be an athletic star in football, baseball, basketball, and whatever other sport he tried, Granville Sr. pushed him towards sprinting. His father’s training style was an eclectic mix, well-researched but also fairly inventive.

“I wouldn’t really run on a track,” Granville says. “He felt it was best to run in the elements, on a big grass field.” An uneven, expansive patch of turf at the local elementary school served as Granville’s primary training ground, rife with gopher holes, dogs, and freeway exhaust. But his father also cross-trained him.

“He wanted to mix everything in the races. He’s a creator, a big time motivator, and truly a student of the sport,” Granville recalls. His father trained him in boxing to work the rest of his body. “Besides Jesus, it was Muhammed Ali in our household,” Granville said. Father and son would watch “Rocky III” and resonate with a sweaty Mr. T shouting “I live alone, I train alone” in the ring.

After graduating high school, Granville ran track for UCLA. “Coming from winning alone, training alone — just me, my sister, my Pops on a big grass field for most of the year — it was kind of a shock to the system.”

* * *

As Granville went through the back turn on the track, his father’s voice emerged.

“As I’m coming off the last 100 meters, I hear my dad’s voice. He says some crazy time like 1:29, and I did the math and was like ‘Man if I can get down this track I think I got the record.’”

Despite feeling like his legs turned to tree trunks in the last 50 meters as the crowd broke into cheering, Granville got through the line in 1:46.45, shaving 0.13 seconds off the record and 1.5 seconds off his previous best. The crowd rose to their feet in applause as the announcer’s voice blared that he had officially set a record.

“I was really stoked for him,” second place finisher Jesse Warren remembers. “I was also slightly confused that he went for it in the semis.” Warren, later a teammate with Granville at UCLA, finished about 60 meters behind Granville in that heat with a 1:53 finish. Warren, who formerly went by Jesse Strutzel, is presently a writer, producer, and actor in Hollywood.

Maybe it was the culmination of his father’s training, the emotions bottled up, or that rare windless night, but Granville would never improve on his mark.

“I think Michael was just in really tight reigns in high school,” Warren recalls. The two were close friends in college, sharing hotel rooms during meets and playing Starcraft together on ancient computers. “His dad wasn’t there to basically say, ‘This is how you’re going to live your life,’ and so he started enjoying the freedoms of college. And I think it was hard for him to balance.”

“You get out of that bubble that worked,” Granville says. “I think I was definitely ahead of the game athletically, but emotionally I think I was a child. The world was new. Going to a movie, hanging out with people, having a girlfriend — all that stuff was just like ‘Woah!’”

Granville reflects, “Imagine that guy, Michael Granville, with so much ahead of him, seeing every year, getting slower. Every year. It got hard to be that guy, to see yourself getting slower and to keep trying to get one magical race. But as far as peaking early — shoot — get it when you can. Because that was my time. And it’s still there.”