The Orion Center welcomed a dozen 20-something year-olds: some in suits and ties, some in loose hippie pants.

Gregory Sandritter followed the crowd into a home-like room. The floor was spotted with colorful sleeping bags, yoga mats, pillows and blankets. In the middle, candle lights glimmered next to odd exotic instruments in crystal and wood.

Sandritter stood disoriented at the door in his white T-shirt and Levi’s shoes. He looked around. At nearly 70 years old, he said he felt like the dinosaur in the room.

“I was skeptical,” he later recalled, “I am from Brooklyn, New York, I am always skeptical.”

His friend Jordan Blake, whom he’d met a few weeks earlier at the San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus, was now sitting legs-crossed, dozens of quartz bowls surrounding him. He sang at a low pitch and brushed the crystal with two mallets.

Next, Blake would add the hum of Native American flutes, and the wind-like whisper of South American shakers.

(Photo credits: Orion Center for Sound Healing)

Sandritter had seen a bowl like those once before. His sister Maria had shown him a crystal bowl a decade or so ago. She said it was a form of alternative medicine, and that it was supposed to help her heal her cancer.

He had been open to alternative medicine in the early days, in his battle against AIDS, he said. Now, he found himself willing to try it again.

“At first it took a lot of letting go of expectations, pre-thoughts of what I ought to do or how I should respond to the sound,” Sandritter said. “But as soon as I got into it, it felt like a getting high of its own kind.”

Sandritter soon became a regular customer of the Orion Center, attending a sound session every other week. When he experienced his first congestive heart failure last winter, he turned to sound meditation for recovery.

His heart was pumping blood to slowly and he felt anxious all the time. Sandritter wanted to take his healing into his own hands.

“I could see that it was starting to get me down, and I realized that I needed once again to become proactive in my own health,” said Sandritter, “This singing-bowl meditation made me very hopeful.”

Two days after he was discharged from the hospital, he bought four crystal singing bowls from Blake: the Grandfather, the Grandmother, and two Pink Oceans of Gold.

The purchase cost him over $4,000.

The business of healing

Sound meditation is becoming a lucrative business in the San Francisco Bay Area.

The practice consists of therapeutic concerts performed with ancient, tribal instruments such as Tibetan or crystal singing bowls, planetary gongs, flutes, chimes and didgeridoos.

Sound therapy dates back to ancient religious Hindu rituals. Its practices began to be commercialized and advertised in fitness and wellness centers in the late 1990s.

“Sound meditation used to be something that is connected to particular religious beliefs,” said Loriel Starr, a certified sound practitioner with a graduate degree in healing arts from The California Institute of Integral Studies.

“Now, it’s not about being a card-holding member. There is no particular qualification or belief-system,” Starr said. “It’s just about getting together and being able to enjoy something that brings benefit and makes people feel better about being alive, more loving and just happier.”

Venues range from cathedrals to discotheques, children summer camps, and therapy clinics; and events cover up to 300 days of the year. Performance dates include Thanksgiving and New Years’ Eve.

In the Bay Area, group performances can cost from $25 to $150. The price doubles for one-on-one sessions.

Starr described a struggle of balancing the business component of sound meditation, with the spiritual and artistic nature of the practice.

“I am professional at what I do, so I am paid for it,” Starr said. “But without a doubt, it is an art as well.”

Practitioner Danny Goldberg said he gave free meditations in the first few years of his practice, but eventually, that changed.

“You have to put a value on it,” Goldberg said. “It’s my time, energy, investment and love going into (the sound meditation) experience.”

As an additional source of income, practitioners also often sponsor services or products for larger companies.

Starr, for example, also works as a certified iRest® Teacher, promoting a patented modern-day practice of Yoga.

Since December 2017, Goldberg has been the Bay Area representative for the Meinl Sonic Energy collection of Tuned Gongs and Instruments, which is also sold on Gongs Unlimited. Goldberg advertises the brand’s top sellers: handmade traditional German-style gongs, and Chinese Chao gongs.

Blake has worked for over a year now as a certified distributor of Crystal Tones singing bowls, four of which he successfully sold to Sandritter three months ago.

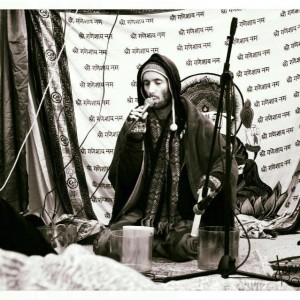

(Photo credits: Jordan Blake)

Sound meditation practitioners usually combine the metallic ring of the singing bowls, with the dark timbre of the gong and lower-pitch instruments, to generate a full and round sound which is said to reduce stress and anxiety.

Blake made his offerings unique, by introducing voice vibrato – a difficult singing practice which creates a hollow rumble of alternating pitches – and the lighter sound of crystal bowls.

“Our bones have a crystalline structure,” Blake said. “…Because of a phenomenon called sympathetic resonance, when I play a singing bowl, the bones and minerals in your body that most closely resonate with that bowl start vibrating.”

Sympathetic resonance is a law of attraction of similar vibrations, he said.

If you play an A-note on a piano and a guitar is laying on a table in the same room, he explained, the guitar’s A- string is going to vibrate. The same thing happens to our bodies, when exposed to crystal vibrations.

Sandritter said he reached a meditative state of calm and mindfulness during his session with Blake.

“I found that (the sound meditation) gave me clarity, and over time even improved my memory,” he said.

A psychological study featured in the National Center for Biotechnology Information in 2013 found that the practice of sound meditation over time enhanced patients’ short-term memory, verbal memory and processing speed task.

David Gibson, president of the Globe institute for Sound and Consciousness, a for-profit therapeutic and research- oriented foundation in San Francisco, said he has applied the practice to Alzheimer, Autism, Attention-Deficit Disorder (ADD), and Post-Traumatic Stress disorder (PTSD) patients with positive results.

His sound recordings are currently played at the Complementary & Alternative Medicine department of Kaiser medical centers in the East Bay.

“It’s a very powerful physical and emotional healing tool,” said Susan Tremont, one of Goldberg’s regular customers in Santa Cruz.

She said that sound meditations alleviate most of her acute neck-, shoulder- and backaches.

(Photo Credits: San Francisco Buddhist Center)

In the national bestseller “The Brain on Music,” psychologist, neuroscientist and musician Daniel Levitin details over 400 studies which scientifically prove the physical benefits of sound.

In the national bestseller, “The Brain on Music,” he details over 400 studies which provide proof.

Melissa Coles, a psychiatric nurse who attends Goldberg’s performances at the San Francisco Buddhist Center, said that, at first, she too didn’t trust the research.

“I had a smaller voice in my head that was cynical,” Coles said. “I wasn’t anticipating that I would feel as joyful.”

She said that the sessions with Goldberg helped her overcome the anguish and stress she accumulated while working with agonizing, sometimes violent patients, through visions.

Alphonse Owirka, an alumnus of UC San Diego’s Institute of Cognitive Science and the founder and CEO of the sound-healing music company SoundRx, attributed this state of clarity and high consciousness to the phenomenon of brainwave entertainment.

“Our brain waves sync up with rhythm and low- frequencies,” Owirka said. “As we are going about our day, our brain waves are usually at a conscious and reasoning beta state from 12 to 14 hertz. When we are alert – at the beginning of a meditation, for example – we reach an alpha state and brain waves tend to be at 10 hertz.”

As the brain waves slow, the subconscious mind emerges, heightening our sense of visualization, memory and concentration, Owirka said.

Californian practitioner Amber Field, said that anyone can understand this research intuitively.

“Sound clearly has an effect on our bodies,” she said. “If you sat for 10 minutes and listened to a jackhammer vs. if you listened to the ocean, you would clearly see a difference.”

All music has the power to heal and soothe, but the intentionality of the practice is what makes sound meditation so powerful, Field said.

However, many remain skeptical.

After attending a free sound bath at the Eagle Rock Center for the Arts in Los Angeles, writer and comedian Julia Prescott described her experience as uncomfortable and not-at-all revealing.

Prescott said the meditation was distracting and awkward.

“Somebody’s stinky feet were in my face for the most part,” she said, “and then I was self conscious about my own stinky feet, and worrying about where my wallet was and where my keys were.”

Prescott was certain that other people around her had felt uneasy as well. It was unmistakable, she said.

“(This sound bath experience) was a little bit more about the person wanting to have a spiritual experience, looking past all of the things that would detract from that,” said Prescott, “It’s confirmation bias.”

In an article for Health Spectator, psychotherapist Miguel Farias and clinical psychologist Catherine Wikholm warn beginners that there is a dark side to meditation.

They call it the ego-rattling effect: an attempt to move beyond our self-centered concerns, which shakes the sense of who we are causing, in some recorded cases, unbearable anxiety.

Farias and Wikholm emphasize that it is not uncommon for meditation to go “wrong”. After publishing their book The Buddha Pill: Can Meditation Change You?, they received multiple letters describing unpleasant and unsettling experiences.

“Instead of dedicating more research to promoting a stereotypical image of meditation as a universal boon,” they said, “we need to be mindful of how it affects people in different ways and try to understand why that is.”

On October 30, 2017, Michelle Robertson, a reporter for SF Gate, attended one of the largest sound meditations yet in the Bay.

The event was given by Sound Meditation SF at Grace Cathedral, and counted over 1,300 participants.

She reported that Guy Douglas, cofounder of Sound Meditation SF, said sound meditations have the power to make cells vibrate. A fellow attendee claimed they can induce orgasm.

These claims were later debunked by electrical engineer Chris Kyriakakis, who specified that the alleged orgasm were probably an overstatement of chills or goosebumps.

Robertson acknowledged the enjoyable and relaxing nature of the concert, but she said she didn’t feel enlightened. The event felt more like a “giant slumber party” than a spiritual experience.

Blake, Starr, Goldberg and Field all agreed that while sound is more effective when played close to or even on the chest and stomach, larger events have benefits of their own.

“Generally, I feel that if somebody is playing an instrument right over your body, you are going to feel the sound effects greater that if you are a hundred feet away,” Field said. “But you can have a whole cathedral laying down and receiving the sound, it really just depends.”

Field offers one-on-one sessions, as well as performances with hundreds of attendees at Labyrinth Yoga Center.

Starr and Goldberg, who performed alongside Douglas and his partner Simona Marie Asinovski at the Oct. 27 event, said that they were glad Sound Meditation SF was reaching more people.

The event at Grace Cathedral felt diluted, and his coworkers made too much of a show by using large sound systems and artificial light installations, Goldberg said.

“I don’t do $800 in Facebook ads,” he said, “I’m much more grass-roots.”

Starr, on the other hand, supported the event.

“There might be people who have to go to an event with 1,300 people to be impacted on a certain level,” she said.

(Photo credits: lorielstarr.com)

But the balance between spirituality and profit is an open debated among sound healers, and in the wellness industry as a whole.

According to the Global Wellness Institute, a research-based nonprofit in the sector, the global wellness market grew to $3.72 trillion in 2016.

Yoga alone is currently $27 billion-market, according to the Huffington Post, with more than 20 million practitioners across the globe.

“The West is great at making money and capitalizing on things,” Field said. “If you look at Yoga back in India: it wasn’t about who could stretch their body in the craziest pose. Yoga was always about … becoming a kinder, more calm and peaceful human being.”

She said that the goal-oriented culture of productivity and ambition is unavoidable in the West, but that ultimately clients will gravitate towards different experiences according to their needs.

“There are people who just want to get a slow (exercise) class and stretch, and teachers who got a 200-hour training and picked up a crystal bowl last week,” Field said. “And then there are people who have a lot of health challenges, and probably want to go to a teacher who has more experience and knowledge. Those teachers exist, too.”

Sandritter said that people can also change their minds.

He was part of that scientific- and goal-oriented culture. For years he had relied solely on traditional health care, until one day the medication his doctor had prescribed failed his heart.

Sandritter said he arrived at that first sound meditation with doubts and cynicism, and left with hope.

“There may not be the proven theory of A plus B, equals C,” he said. “But of all the things that brought me to this point of life, I cannot deny that those singing bowls were among the most helpful.”

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated to clarify which event Danny Goldberg attended, as well as the company that he works for.