Palo Alto is exploring ways to redesign four of its Caltrain railroad crossings that have become traffic bottlenecks and scenes of frequent accidents.

In what could be a costly multi-decade process, officials are planning changes to the crossings at Charleston Road, Meadow Drive, Churchill Avenue and Palo Alto Avenue, where the road and train tracks intersect at the same elevation, or at-grade. Palo Alto has four other crossings where the road and the tracks are located at different elevations.

The city is hosting four roundtables this month, starting Nov. 14, to discuss ways to separate the road from the tracks at each crossing. Grade separations would allow road traffic to flow independently of passing trains and reduce the chances of collisions between trains and vehicles.

“We don’t want to see any more of these incidents where drivers inadvertently turn down the tracks, because their GPS device told them that there was a street there,” Palo Alto resident Penny Ellson said, referring to an October accident at the Charleston Road crossing.

All incidents that occurred on the Caltrain tracks in Palo Alto since January 2016 happened at or near one of the four at-grade crossings. These incidents include six motor vehicle strikes and one pedestrian strike. One of the motor vehicle strikes and the pedestrian strike ended fatally, according to Caltrain spokesperson Dan Lieberman.

Another issue is traffic. As the gates close for 45 seconds every time a train passes, up to more than 25 vehicles line up on each side of the four at-grade crossings during daily peak hours, according to the city.

The city expects this number to triple over the next decade, as Caltrain and High Speed Rail – if it is built – will increase their service from 10 to up to 20 trains per peak hour counting both directions.

“There is a point where there is going to be so much train traffic that the city’s street network is going to fail to function properly,” Palo Alto Chief Transportation Official Joshuah Mello said. “So, the quicker we can deliver these (redesigns) the better.”

Although Palo Alto wants to act fast and the city council is expected to vote on the project next summer, grade separations typically take more than a decade to plan and build, according to Mello.

But the city and Caltrain plan in the next few months to take steps to improve safety, including the construction of new medians, and adding signs, striping and traffic signals at the various intersections.

Palo Alto’s efforts to address ongoing safety issues and growing traffic congestion at at-grade crossings are part of a broader problem throughout the Caltrain system.

All of Caltrain’s 42 at-grade crossings will have to be redesigned, according to Nadia Naik, co-founder of Californians Advocating Responsible Rail Design, a Palo Alto-based volunteer group.

Grade separations are currently being planned or built at 15 of those crossings, according to Lieberman.

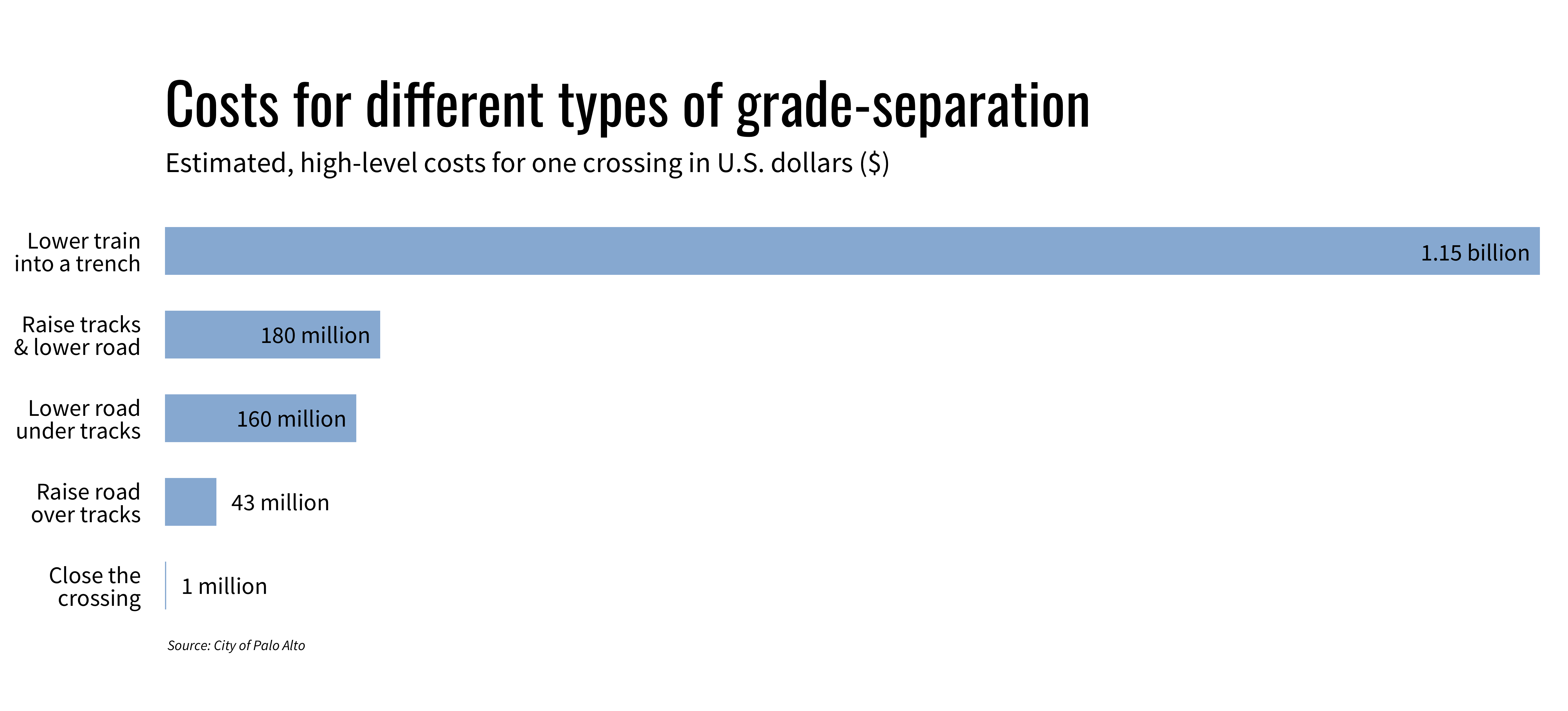

Grade separation projects typically cost between $125 million and $150 million each and are financed by a combination of federal, state and local money, Mello said.

Last year, Santa Clara County voted in favor of Measure B, a countywide sales tax that will provide $700 million for the redesign of eight at-grade crossings in Sunnyvale, Mountain View and Palo Alto. As the money will be divided between the cities and spread over the next 30 years, it will most likely not cover the cost of Palo Alto’s four grade separations, according to Mello.

“In all likelihood, we need to identify a more robust funding package,” Mello said. “This will be a long process.”

Costs, construction impacts and aesthetics vary widely among the different types of grade separations and will be discussed at the city-organized roundtables this month. Options include lowering the train tracks into a trench or a tunnel, lowering or raising the road and a combination of lowering the road and raising the tracks.

Another option is closing a crossing for car, bicycle or pedestrian traffic entirely. While this would cost less than a grade separation, it would increase traffic congestion at nearby, already grade-separated crossings, such as University Avenue, Embarcadero Road, San Antonio Road and Oregon Expressway. As a result, the city might have to build a costly expansion of one of those crossings, according to Palo Alto City Councilmember and chair of the city’s Rail Committee Tom DuBois.

At the moment, the trench seems to be the community’s most widely supported type of grade separation, according to Mello. It would reduce noise from the train, but the construction process would be difficult, as the train tracks would have to be moved to the side during the time of construction, as to not interrupt train service, Naik said.

Lowering the road under the tracks could require displacing some residents who live close to the crossings.

“This is a big community question and it is going to be very disruptive,” Ellson said. “(But) I do think that grade separation is going to be the solution that gives us all the things we need.”