The day before Thanksgiving, Sayed Hofioni finally opened the door to his family’s new home.

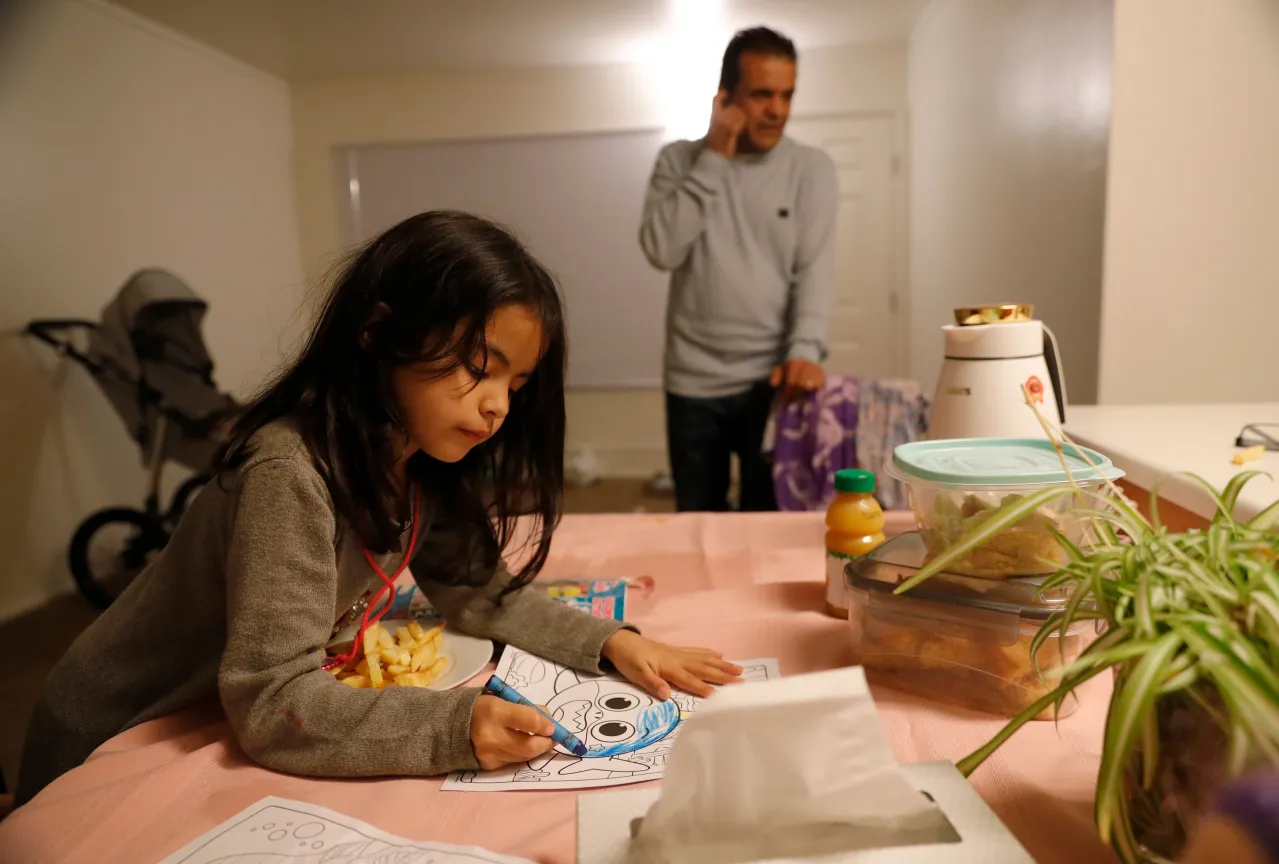

His daughters, Kowsar, 5, and Zainab, 3, rushed inside, eyes wide and giggling. His wife, bundling their 3-month-old baby in her arms, followed closely behind. It had been three months since they fled Afghanistan on a military plane — and almost as long that they had spent waiting in a single room at a Contra Costa County hotel. The small space grated on the entire family, and every day, Hofioni’s daughters would ask him: “Padar,” which means father in their native language Dari, “when are we moving out of here?”

When the family finally found a home late last month in Antioch, the two-bedroom apartment before them felt unreal.

“I saw a very good smile on my family’s faces,” said Hofioni, 55. “After everything we’ve been through, that was priceless.”

The Hofionis are among hundreds of Afghans who have arrived in the Bay Area since August. When they first landed in California, they were greeted by resettlement agencies, non-profits and the county government, all of whom tried to help them do the nearly impossible: find an affordable home in one of the country’s most expensive housing markets.

“Every night, I couldn’t sleep because I was thinking: What can I do to find a house for this family?” said Yasamin Taher, the Hofionis’ case manager at Jewish Family & Community Services East Bay (JFCS). “Landlords often require tenants to earn three or four times the monthly rent — plus deposit. I was thinking about them all the time.”

As the crisis in Afghanistan unfolded, Gov. Gavin Newsom called California “a place of refuge” for Afghans fleeing the Taliban, citing the state’s large Afghan population as proof of its hospitality. In 2019, 41% of all Afghan immigrants in the U.S. lived in California, with Fremont and Concord housing some of the biggest Afghan populations nationwide.

But in early September, the State Department discouraged Afghans from resettling in the Golden State, warning that refugee benefits were unlikely to cover living costs. Still, with more than 5,200 refugees projected to arrive in California, the state is slated to take in more Afghans than any other state — almost the entire number of those expected to arrive in the next two most populous states, Texas and Florida, combined.

After living in the Bay Area decades earlier, Hofioni thought his familiarity with the region, along with its large Afghan community, would create a soft landing place for his family. That’s what California felt like the first time he fled Afghanistan in his early 20s. He lived in California, Nevada and Virginia before returning to his home country in 2011, where he got married, had children and began to settle down. Instead, just 10 years later, Hofioni found himself fleeing Afghanistan again.

The second time he came to California, he was met with a new set of challenges.

In August, the moment the Taliban seized Kabul, Hofioni rushed his family to the airport in a desperate effort to leave the country.

He was certain that his 16 years in the U.S. — along with the citizenship he acquired while living there, and his work teaching Afghan language and culture to U.S. soldiers — would put his family at risk. (The family asked that the Bay Area News Group not identify his wife out of concern for the safety of her family in Afghanistan.)

For days, they tried to push through the swelling crowds. By the time the family made their escape onto a military plane, their youngest of three children, Tajalla, was only 10 days old. “It was very hard, especially on my wife,” Hofioni said. “Ten days after having a C-section, she spent nights and days at the airport. But she is so strong. She never stopped being brave.”

From Doha, they flew to Italy. From Italy, to Philadelphia. And from Philadelphia, they landed in Oakland, weeks after they closed the door on their Kabul home.

Resettlement agencies in the Bay Area, which include the International Rescue Committee (IRC) and JFCS, are helping refugees transition to their new lives in the U.S. But at the same time, the agencies are overwhelmed.

Jordane Tofighi, director of the IRC in Oakland, said the organization is finding out refugees are arriving only 24 to 48 hours before they land — as opposed to a typical turnaround time of between two weeks to several months to prepare individuals’ resettlement cases.

During the first month of the organization’s fiscal year, which began on Oct. 1, the IRC saw 208 Afghan refugees — 80% of their total capacity for the entire year, Tofighi said.

After fleeing crisis, thousands of Afghans are arriving in the U.S. with no job, credit score or rental history. As a U.S. citizen, Hofioni is being supported by a slightly different combination of organizations, but the challenges remain the same. In Contra Costa County, the median monthly rent for a two-bedroom apartment is $1,866 — 70% higher than the national median. If a landlord requires tenants to make three times that rent, Hofioni would need to make over $67,000 a year.

Unsure of where he could afford to settle, Hofioni has had a difficult time landing work in the Bay Area. In the past, he worked at a non-profit focused on reducing gender-based violence in Afghanistan. He taught language and culture to U.S. soldiers at a North Carolina military base. He’s driven taxis in San Diego. And he’s been a blackjack dealer in Las Vegas. But with the back-and-forth on housing, he wasn’t even sure where to look for his next job.

“When you are coming from another country, you think that you’ll come to America and everything will be there,” said Taher. “But when they arrived, it was a different story.”

But today, they have two bedrooms in an apartment of their own. JFCS will help the family with rent over the next few months, Taher said, until Hofioni and his wife can find jobs of their own.

Despite all the challenges, Hofioni said he never gave up on the state where he dreamed of building a new home.

“I love California — who doesn’t?” he said. “I wanted to try to come here and have a better life for my kids and my family. That’s all I really want.”

This story was first published by The Mercury News.