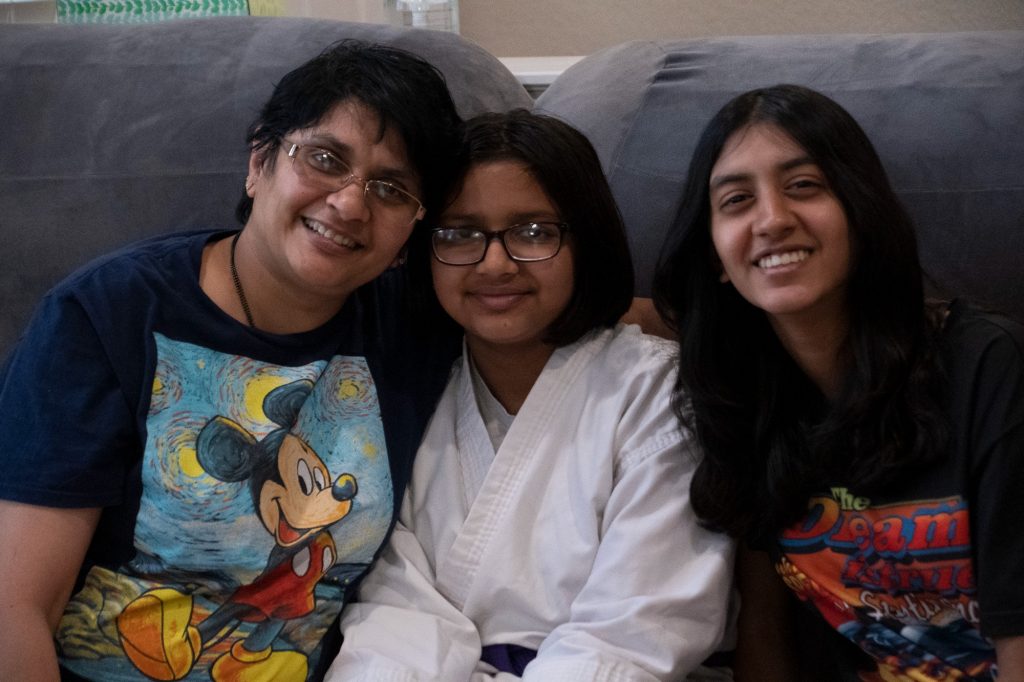

Darshana Purohit had just started consulting for a clinical research committee and was celebrating her second year as a paint studio owner in the East Bay suburb of Pleasanton. Then, on March 16, 2020, Alameda County announced its first shelter-in-place order.

Overnight, her studio shut down and Fairlands Elementary and Foothill High School, where her two children study, cancelled classes for two weeks. Three months later, she was laid off from her consulting position with one day’s notice, cutting her family’s income in half.

The pandemic put her family in debt and forced her to apply for unemployment benefits, refinance her home and sell her car.

“The bills are coming. The rent is coming. We haven’t paid in like 10 months now… We remind our kids a lot that things are expensive,” Purohit said.

Stories like Purohit’s have become increasingly common in California. Since the beginning of the pandemic, California’s job market has lost the largest percentage of parents of school children in the country, trailing only Nevada and Michigan, an analysis of U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey data shows.

In weekly Census surveys conducted between April 2020 and March 2021, more than two million or nearly 60 percent of California moms and dads reported losing employment income. Low-income and single parents had it worse, reaching peak rates of 69 percent and 82 percent respectively in July 2020, according to Census Pulse data.

The pandemic heightened the plights of already vulnerable American communities.

Mothers and minority communities bore the brunt of pandemic job cuts. The Census estimates that nearly one in two mothers with school age children willingly or forcibly left work by spring 2021. Latinos and Black women, who were nearly three times as likely to die from COVID-19 than white males during the pandemic, accounted for most pandemic-related job losses and have been struggling the most to recover.

Essential workers also faced disproportionate health and economic impacts from COVID-19.

While most Americans sheltered in place in 2020, Marisol Alcantar, a farmworker in Bakersfield, Kern County, was called into work for eight hours every day.

On the fields, Alcantar was told to ignore social distancing measures, and had scarce access to handwashing facilities and masks. And when last winter she fell ill with COVID-19, she was left without health insurance or a support network.

"I’m here by myself. I have no family, I’m completely alone so no one can help me with [the kids]," Alcantar said. "It was very very hard for me.

As an undocumented worker, Alcantar was not offered paid sick leave, according to Leydy Rangel, the national communications manager at The United Farm Workers Foundation. Alcantar’s illness forced her to miss one month of work, jeopardizing her family’s food security and nearly costing them their home in Bakersfield.

Where moms and dads lived also affected their job stability.

Job losses were focused in the Census-designated metropolitan areas extending from Los Angeles to Anaheim, and from Riverside to Ontario. In the Bay - where the median household income, at $114,000, is about $40,000 higher than in the southern metropolitan areas – parents fared better despite experiencing some highs in July and December of 2020.

The pandemic has left parents exhausted and exasperated.

Some parents like Purohit and Alcantar were direct victims of the virus and the pandemic-induced recession, which left millions of Americans bedridden and jobless. However, Jessica Lee, a Staff Attorney at UC Hastings’ Center for WorkLife Law, believes that there are many more who were failed by the “system”.

She described distressing stories of employers meeting parents’ requests for more flexible schedules with ultimatums and threats.

While women and individuals with disabilities can sometimes resort to non-discrimination law if they are wrongfully laid off or forloughed, Lee said “there’s [currently] no law that specifically protects parents.”

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act, a federal safety-net, which provided parents with 12 weeks of job-protected and partially-paid leave, expired at the turn of 2020. While the U.S. Department of Labor extended employers’ tax credits for paid sick leave, offering workers leave is no longer mandatory in 2021.

“It’s a recipe for disaster,” Lee said.

For more information about the methodology behind this data story, visit https://github.com/carolineghisolfi/California_Working_Parents