On Sept. 28, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed legislation focused specifically on farmworker health and safety during the pandemic. But some advocates say more is needed to help this vulnerable population.

“Although (the bill) is a good start to educate farmworkers and to bring about awareness, we still need to tighten up the bolts more,” Hernan Hernandez, president of the California Farmworker Federation said, saying that the bill is “watered down.”

Farmworkers, as essential, often poor workers who live in overcrowded housing, have been hit particularly hard by the pandemic. The package aims to alleviate those problems by promising better enforcement of health guidelines, funding an educational outreach campaign on guidelines and sick leave, and requesting more state-funded housing.

But in Monterey County, where two-thirds of the nation’s lettuce is produced, farmers and growers were already doing most of the work that the package sets out to accomplish.

“Having skilled, healthy workers is very important,” said Carolyn O’Donnell, communications director for the California Strawberry Commission, a trade association. “So we did all of this before the legislation finally caught up.”

O’Donnell is a part of the Monterey County Coalition of Agriculture, which brought together farmers, farmworker advocates, health experts and county officials starting in early March to address the needs of farmers and farmworkers during the pandemic. The group routinely shares educational information, informed by the health experts and made culturally effective by the advocates, for farmers to distribute to their workforces.

California Assemblymember Robert Rivas, who introduced the legislation, said that the industry in this county was very “proactive” in establishing local safety guidelines for agricultural workers.

“I give them a lot of credit, and I commended them on their work that’s really leading this effort,” Rivas said. “Unfortunately, the same couldn’t be said throughout the agriculture industry across the state of California, and so that’s what compelled us to introduce this first-in-the-nation COVID-19 farmworker relief package.”

The Grower-Shipper Association, for example, created a housing program for farmworkers who are exposed to COVID-19. Under this program, the association partners with hotels in the county to fund housing for both permanent and seasonal employees who may have been exposed to the virus, either at home or at work. Workers do not need to have a positive test result to qualify, which is easier for those who are unsure how to navigate the healthcare system or who are fearful of going to get tested, Chris Valadez, president of the Grower-Shipper Association, explained.

“We wanted our employers to be in the position to be able to do something about it – to help reduce the risks of any on site or worksite COVID-19 transmission by making housing available to ag employees free of charge,” he said.

The Grower-Shipper program was the blueprint for the state’s “Housing for the Harvest” initiative, which began in July and was extended as part of the farmworker relief package. But, unlike Grower-Shipper, the state requires either a positive test result or proof of exposure to qualify.

Rivas pointed out that Monterey County is not covered by the state’s housing program. Areas like the Central Valley, Central Coast and Imperial Valley, which have higher numbers of agricultural workers, are currently being prioritized, according to the state.

“We’re still advocating for our region to be a part of this program,” he said. “Although the governor cited our region and in the work we had done as being the model that launched the statewide program, we have yet to receive any resources or any funding.”

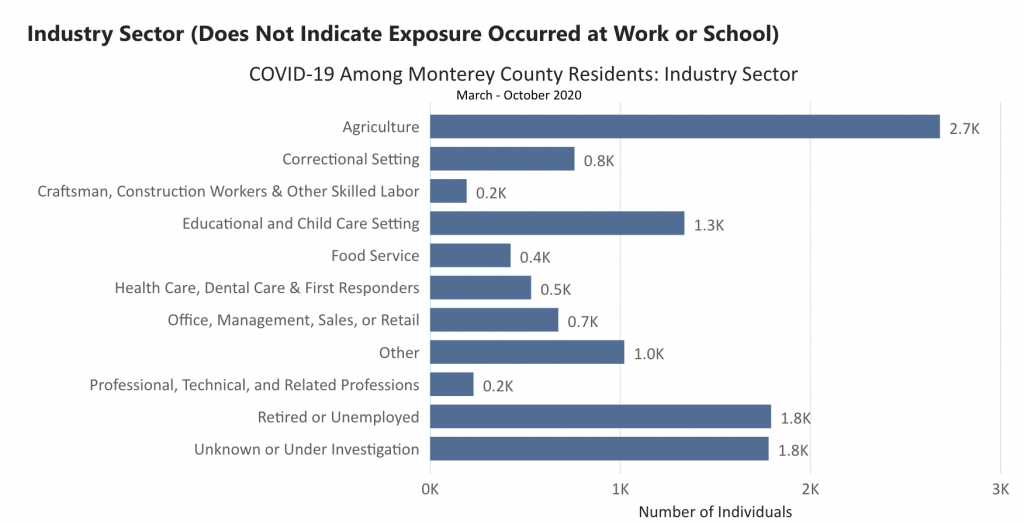

But even with these measures, farmworkers in Monterey County are still getting sick, Rivas noted. The California Institute for Rural Studies found that agricultural workers in the county were three times more likely to get the virus than non-agricultural workers. That means that for counties with less industry support, the issue could be even worse, Rivas said.

One weakness of the bill is that it relies on the state’s occupational health and safety branch to enforce its requirements, Hernandez said, which means that workers would need to report violations to the agency. But farmworkers who are undocumented do not want to get involved with the government at all for fear of being deported, he explained, adding that community-based organizations tend to work better.

“Especially these past four years with this federal administration, there’s more fear, there’s more anxiety about really trusting these institutions,” he said. “The main fear is that… if they get benefits, if they are part of this program, that their name is going to be kept in the database and then they’re not going to be able to legalize themselves in the future.”

About half of U.S. farmworkers are undocumented, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The Center for Farmworker Families estimates that in California, it’s about 75%.

“One of our greatest challenges is trying to get these vulnerable residents the resources and the help they need, but also ensuring that they step forward to receive this help… because of this fear of deportation,” Rivas said. The educational component of the bill will reach all agricultural workers, he explained, and will emphasize that workers have the right to reach out to Cal OSHA “regardless of immigration status.”

While industry leaders plan to continue creating their own programs for protecting workers, Rivas and farmworker advocates plan to keep pushing for governmental action.

“Overall, we’re grateful that it happened, but now we got to continue with the policy changes,” Hernandez said. “And I think COVID-19 has a lot of opportunities to influence policy.”

“We’ve got to do a lot more in Sacramento, we’ve got to do a lot more at the local level, to ensure that we’re providing these resources and expanding opportunities for the incredibly vulnerable families and workers in our state,” Rivas said.