Fireworks dazzle over the skyline, car horns and music fill the summer air, and teens hang from car windows or cram into the beds of trucks doing laps through city streets in jubilee. Every July, this is how Palestinian teenagers celebrate the results of their matriculation exam commonly referred to as the Tawjihi. This year, however, the coronavirus pandemic has prompted an overhaul of the Palestinian school system in the final months of the academic year, affecting students’ readiness for one of the most important milestones in their education.

The Tawjihi, also known as the General Secondary Education Certificate Examination, is still set to be administered in person to over 75,000 Palestinian 12th graders, according to the most recent announcement from the Palestinian Ministry of Education. The first of ten days of exams on a variety of subjects is scheduled for May 30. Each student typically takes at least three subjects per week.

Minister of Education Marwan Awartani confirmed on April 27 that the tests will be held this year “in accordance with the established criteria from past examinations” but promised an increase in test sites and proctors and that social distancing and sanitation measures would be enforced at all testing facilities.

While COVID-19 infections have soared past four million cases worldwide, forcing the United States to cancel in-person high school standardized testing until September, the Palestinian territories have managed to keep their caseload low. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs reported 605 confirmed cases in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza Strip, with over 54,000 tested and only five deaths as of May 26.

These low numbers are likely thanks to the swift response on the part of the Palestinian Administration, which included curfews, bans on travel between cities, and school closures as early as March 8.

Shortly after, the Ministry of Education created an online platform of Tawjihi resources. Later, they also decided to remove from the test questions on units many classes hadn’t yet covered by March 8. These changes have been helpful to some students who are taking advantage of the extended study period.

Uncertainty early on

“Everyone cares about the Tawjihi,” said Mohamad Abdalhadi, a 12th grader at Deir Dibwan Boys Industrial Secondary School, a government-run school near Ramallah. Abdalhadi plans to take the industrial Tawjihi, one of the various Tawjihi streams students follow through high school that include humanities, science, math and art.

Abdalhadi, who lives in the town of Birzeit and who travels one hour to school each morning by taxi and then bus, appreciates the extra time at home to devote to studying — sometimes 12 hours a day, “especially during Ramadan and this quarantine,” Abdalhadi said.

However, the recent changes have also come with challenges, major and minor, to students who are preparing for the final step in their high school education.

“It’s more pressure this year,” said Basil Hijaz, another 12th grader from Birzeit, who attends Al-Ameer Hasan Secondary School and plans to sit for the science Tawjihi this month.

Hijaz is grateful that the material on the exams will be pared down. However, he’s anxious about whether changes will raise the stakes.

“Everyone is concerned that the exams will be more difficult,” he said.

The Ministry of Education did not provide answers about the specifics of the exam until more than a month into the West Bank’s shelter-in-place policies took effect.

Until mid-April, Hijaz said, “We didn’t know which subjects to study. Do we have to study the curriculum we didn’t cover on our own?”

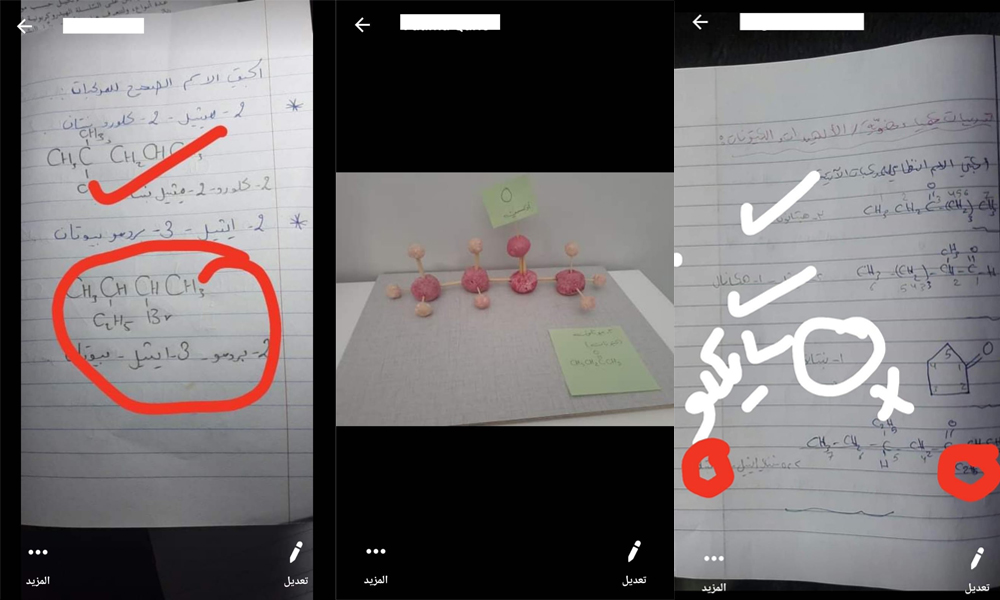

Teachers shared their students’ confusion at first. Sana Jaber, a chemistry teacher at the Orthodox School of Bethany, a private school in the West Bank, said that her pupils were fortunate that they set up an online class schedule right after schools closed, and were thus able to complete the usual curriculum.

Now, she relies on Powerpoints and social networking platforms like Facebook Messenger and Zoom to instruct students remotely and provides outside material like worksheets, assignments and YouTube videos for further review.

In the rest of the West Bank, she said, “most students didn’t get this opportunity” to continue classes immediately online, “because not all teachers were asked to start distance learning [and] were [a]waiting instructions.”

Additionally, only private schools implemented online classes at all. Government-run schools canceled classes entirely, ending the school year prematurely. The vast majority of students in the West Bank attend government-run schools.

Distance learning highlights internet and tech access issues

Distance learning has also revealed and exacerbated existing socioeconomic and educational disparities among students.

“The [Tawjihi] curriculum is not easy,” Jaber said, especially for those who don’t have stable access to the web. According to the Arab Center for the Advancement of Social Media, only two-thirds of Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza used the internet in 2016, and 3G was only made available to Palestinian telecom providers in 2018 due to Israeli frequency allocations. Many communities, especially rural ones, still experience access issues.

Jaber added that often families of four or more children share a single laptop or phone, which further disadvantages them during this time. Another teacher in Huwwara near Nablus agreed that “there is a good percentage [of students] that does not have a smart device.”

“All of this may affect their performance,” said Jaber. Now that students are no longer coming together at school, there’s no way to ensure equal opportunities for the most vulnerable of students who depend on school not only for its resources, but often for meals and social and mental health support as well.

Hijaz said that he knows other students who don’t have reliable wifi or computers to contact their teachers during this time; if it wasn’t for Code for Palestine, a three-year programming camp which gifted him his laptop, he’d have to share a computer with his younger brother while studying for the Tawjihi.

Abdalhadi noted another limitation: Zoom and other online tools are largely in English.

“I’m considered pretty advanced in English,” he said, which allows him to navigate Zoom’s interface easily, “but my classmates are less experienced, so it was a little bit hard for them to get it.”

Disparities in East Jerusalem

Disparities in internet and technological access are felt sharply in East Jerusalem, where 11th grader Raghad Nassar lives and attends Ibrahemiah College.

Palestinian schools and students in East Jerusalem struggle with different problems from those in the West Bank. Much-needed funding from the Israeli government is conditional on their adoption of the Israeli curriculum instead of the Tawjihi system. The student-teacher ratio is much higher than that in West Jerusalem due to inadequate classroom space and teacher shortages resulting from restrictions on movement for professionals coming from the West Bank.

Education for Palestinian children is also much more complicated in East Jerusalem than in the West Bank, with school administration split among different authorities using two different curricula. Most Palestinians attend Tawjihi schools administered by the Waqf (the Islamic Trust Fund affiliated with the Palestinian Administration), UNRWA or private organizations. However, a minority of students attend Israeli public schools and take the Bagrut, the Israeli matriculation exam. This divide exists in Nassar’s household—her sister attends an Israeli public school while Nassar attends El Ibrahemiah and plans to take the Tawjihi next year—so Nassar has a close perspective on the inequities in East Jerusalem that have been amplified by this pandemic.

“We don’t have as quality a [technological] system,” Nassar said of her school compared to her sister’s, the latter of which has been hosting online classes during Israel’s lockdown. “My school does not provide Zoom calling.”

Instead, “most of the classes send YouTube videos to understand our subjects,” Nassar said. “Then we study ourselves, get our own resources. Then the teacher [gives] us a test online.”

This disconnect between the standard curriculum and what she and her classmates are actually learning, she fears, might affect her performance on the Tawjihi next year.

“All our future depends on… the test,” Nassar said. “Of course I am worried. I am very worried.”

Not even the students’ hopeful celebration plans have been spared from the impacts of the pandemic. Karim Ismail, a student in Beit Iba taking the arts Tawjihi this year, said, “I am going to have a simple family party… because [coronavirus] disrupted all my future plans to celebrate the Tawjihi score.”

While Hijaz is bummed that his graduation ceremony—and all Tawjihi parties—were canceled, he said, “The moment the results come out I will be with my family, and they’ll be the happiest.”