John Gierach lives a life most anyone would envy. His occupation is tied to one of his greatest passions: fly fishing. At 74, Gierach writes columns for the Redstone Review and Trout Magazine and is the author of 20 books dating back to the 1980’s. He does a majority of his writing from his home in Lyons, Colorado but travels across North America in search of bigger fish and unique destinations.

Gierach, whose 21st book, “Dumb Luck and the Kindness of Strangers,” is due out in June, has had a passion for writing from the onset of his education, and he had little interest in material belongings.

“Being a fishing writer just doesn’t make economic sense,” Gierach said, “except that you’re having fun and you’re doing what other people do on vacation or when they retire.”

Upon graduating from the University of Findlay in 1967 with a degree in philosophy, Gierach traveled west to the Rocky Mountains to begin his budding career. Gierach took inspiration from Ted Trueblood, a former editor and writer for Field & Stream, for pairing the outdoors with his love of writing.

“He lived, what seemed to me, the ideal life,” Gierach said. “He had a cabin in Montana and he had a little house down in Florida. He, his wife, and his birddog would hunt and fish their way north in the spring, and in the fall, they would hunt and fish their way back south.”

Gierach himself is unmarried without children, but Trueblood’s career path offered him a glimpse into a potentially similar life. In pursuit of this idealistic lifestyle, Gierach worked odd jobs in and around the Denver area. His first job in the summer of 1968 was in the Montezuma Mine, an operation about two hours west of Denver. Gierach said the mine served as a front for “some other shady operation,” and the owners hired anyone with a pulse to do the work. Gierach would bounce around from a logging operation, a landscaping crew, and even installing insulation to sustain himself, but these were relatively short stints. The longest Gierach worked at one place before committing to writing fully was as a garbage man at the Boulder Waste Management Center.

“It was a great job that paid pretty good,” Gierach said. “The guy I worked for was named Stickman; he was an ex-Hells Angel. He didn’t care what you looked like or what you acted like so long as you got the work done. I liked that.”

Gierach enjoyed this job. He was able to work alone and it paid better than minimum wage. Additionally, he would find all kinds of interesting wares in the trash, ranging from acoustic guitars to kitchen utensils to pornography. Heaps of pornography. He and his coworkers would gather up their monthly hauls and sell them at the Denver flea markets.

“We used to piss people off because we never put prices on anything,” Gierach said. “We’d just put the stuff out and somebody would say, ‘How much for that frying pan?’ and you’d say, ‘I don’t know, what do you want to pay me for it?’”

At that time, Gierach was not worried about advancing his career or how much money he was making. He wanted only to live life on his terms. Food and rent were relatively cheap with enough people to chip in, and no one had insurance or other extraneous expenses. Looking back, Gierach admits it may not have been as perfect as he makes it out to be, but it was the life he wanted.

“I used to rent a one-room apartment in Boulder, Colorado for $25 a month, including utilities. And it was a shithole, but it was cheap and it kept the weather out,” he said.

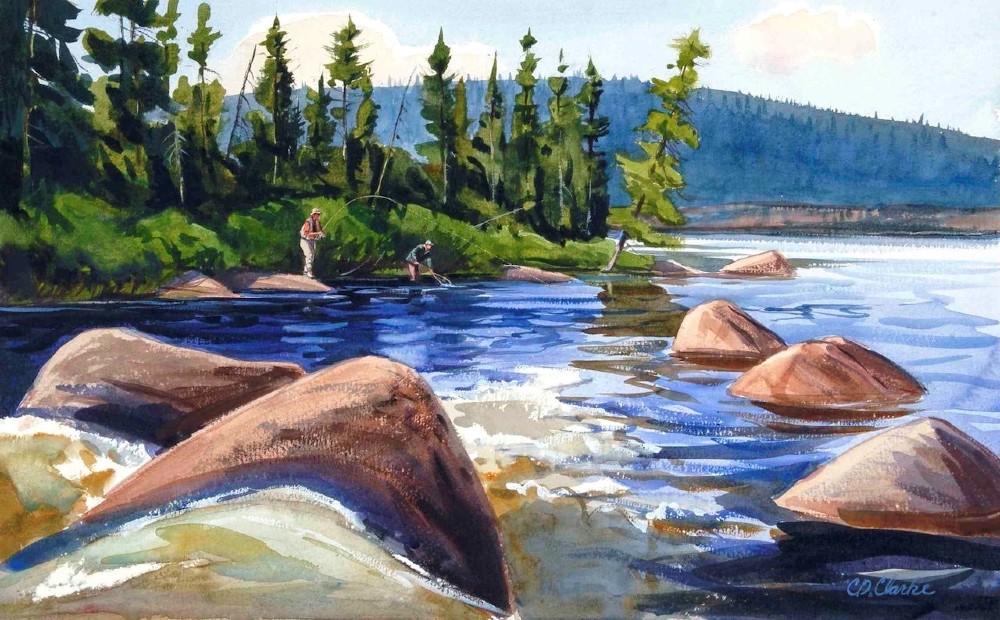

Gierach is genuine and candid. His wry observations make his work pop and appeal to down-to-earth folks like himself. His writing approaches sensory overload in the way he depicts scenes from his outings. Seemingly plopping his reader waist-deep in the river, rod in hand, Gierach is meticulous with his word choice and uses vivid imagery.

In “Trout Bum,” Gierach’s most well-known book, he says, “Trout are wonderfully hydrodynamic creatures who can dart and hover in currents in which we humans have trouble just keeping our footing. They are torpedo shaped, designed for moving water, and behave like eye-witnesses say U.F.O.s do, with sudden stops from high speeds, 90-degree turns, such sudden accelerations that they seem to just vanish.”

Descriptions like these, about a seemingly uninteresting creature, are what draw readers to Gierach’s work. Whether they are outdoorsmen or not, he has an uncanny ability to connect to a diverse collection of people, likely due to the rich life experiences he’s encountered. Gierach is a product of the hippie culture of the 1960’s and the social rebellion that came with it.

“We just thought there was going to be a revolution soon,” Gierach said, “and we would either all be killed or we would usher in a sort of hippie utopia, so there wasn’t a lot of thinking about the future.”

The 1960’s were a tumultuous time in American history, but Gierach made the most out of the situation. The conflict in Vietnam was one reason for this sentiment. Gierach’s draft number all but assured a deployment to Asia, yet he was not called to serve.

“I was opposed to the war. I wasn’t a pacifist, but I was definitely opposed to the war. I supposes if I had gotten drafted, I would have ended up in Canada,” he said.

Gierach put the outdoors, and fishing in particular, on hold during his college years as he explored other interests, both academically and socially. He took full advantage of his surroundings and the opportunities presented to him.

“There were a billion great books to read and women and beer and marijuana and rock and roll,” Gierach said. “A lot of things got in the way (of fishing).”

The graceful art of flinging an imitation fly toward a lurking trout refocused Gierach’s attention to fishing. He had grown up fishing with bait, but it was in Colorado that he first witnessed fly fishing in action. His passion for the sport eventually spilled over into a profession. Realizing other guys were actually being paid to stand in the river all day, Geirach submitted his first fishing article to Fly Fisherman magazine. The story sold and began his writing career.

Gierach could easily tell fishing stories. He could talk at length about landing a giant brook trout or the thrill of pulling a creature up from the depths of a percolating pool, and that could be his niche. But Gierach’s ability to capture the essence of a day on the water, the significance of the event from a greater perspective, is what separates him from other writers.

“Nick Lyons famously said, ‘The best fishing stories aren’t really about fishing,’” Gierach said. “It’s about a guy I met or the history of a little town along the river.”

John Gierach has an inquisitive mind. He is a thinker. However, unlike other writers or English majors, he doesn’t believe there needs to be a hidden meaning in an author’s writing.

“People were always asking, ‘What did the author mean?’” Gierach said. “I always thought, ‘Well, why can’t he mean just what he said? Why does it have to be a secret?’”

A claim like this seems paradoxical coming from a man who wrestles with big questions like the meaning of life. Yet Gierach’s nature is simplistic and straight-forward. One might guess

that the solitude of fishing alone on the river might prompt a person like Gierach to keep up an endless banter of inner dialogue.

But this is not always the case.

“At its best, you don’t think about anything except what you’re doing,” Gierach said. “Like ‘Where’s the fish? What is he doing? What will he bite? Where do I have to stand to get the best drift?’…Stuff like that. At other times, your mind races like your mind always races. It’s a constant feedback loop.”

Gierach knows he has lived a life built on his own terms. He reflects often on his experiences, and cherishes the connections he has made with others.

“I’m in my 70’s, I’ve had a great time, and I’ve made a living,” Gierach said. “And if I got sick and died now, I couldn’t complain. If I got sick and died when I was 30, I would think, ‘Fuck, look at all the stuff I’m missing.’”