Mountain View’s plan to develop 412 acres into housing, office space and retail will be put to a Nov. 5 City Council vote after four years of debate over how to start closing the gap between new jobs and new homes in the city.

Leaders of the East Whisman Precise Plan are tweaking the final details to answer concerns of developers, school district officials and the city council.

“We know we need the housing. That’s the overwhelming need,” said Eric Anderson, project planner and environmental safety coordinator for the City of Mountain View.

Housing is the primary goal of the plan, though the project is also described as a “highly sustainable, transit-oriented employment center.”

The project aims to create a walkable neighborhood with 5,000 new units of housing — 20 percent of which will be “affordable” — and 2.6 million square feet of office space. There will be three open space areas created for every 1,000 residents. If passed, it will be implemented as part of the Mountain View 2030 General Plan and work would begin soon.

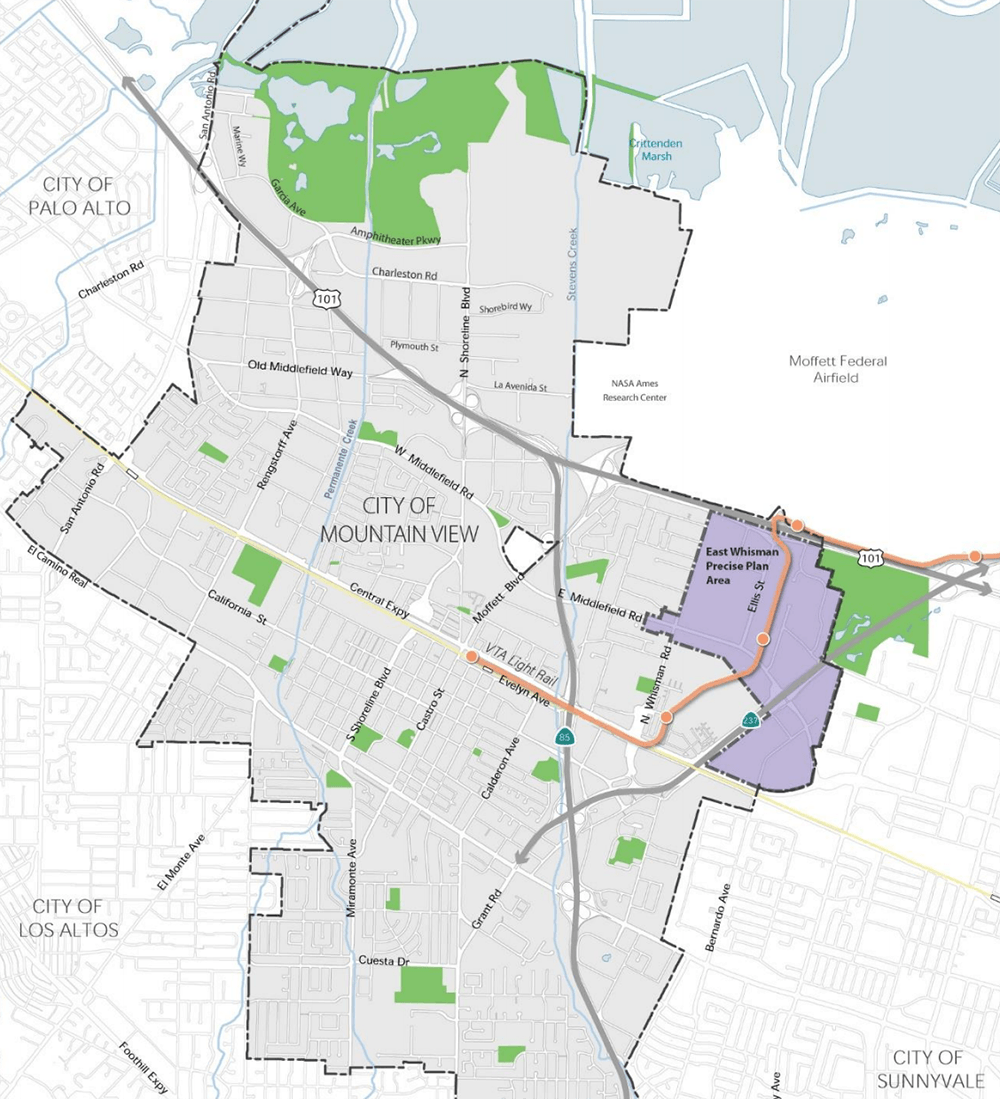

The area is “bounded by the U.S. 101 freeway and NASA Ames/Moffat Field to the north, Sunnyvale city limits to the south, and Whisman road to the west,” according to the plan.

Anderson acknowledged the myriad of stakeholders with investment in the outcome. His team is constantly “trying to find win-win solutions,” he said in an interview.

The main focus is to build more housing in the job-dense area.

“We suffer from the fact that we have too many good jobs,” said Lenny Siegel, former Mountain View mayor and current executive director of the Center for Public Environmental Oversight, a local organization that educates stakeholders on environmental clean-up and protection. “And it’s hard to keep up with employment increases — not just by Google, but by start-ups — with new housing. So I can’t say we’re going to end up with a balance between jobs and housing. My goal is to say, ‘It’s not going to get any worse,’”

But some residents are asking if East Whisman is the right place for more housing. The proposed development is atop one of Santa Clara County’s 23 Superfund sites — land contaminated with hazardous waste. Residents have expressed concern about the potential harm of living near a Superfund site at meetings and on apps like NextDoor.

However, Siegel, who has worked on contamination issues in the area for over a decade, says there is no reason to fear. Mountain View has a uniquely close relationship with the Environmental Protection Agency, with stronger policies surrounding Superfund redevelopment than any other city in the Peninsula. Siegel says that he “feels comfortable” telling anyone that they can move their family into the new development, since all potential contaminants will be closely watched.

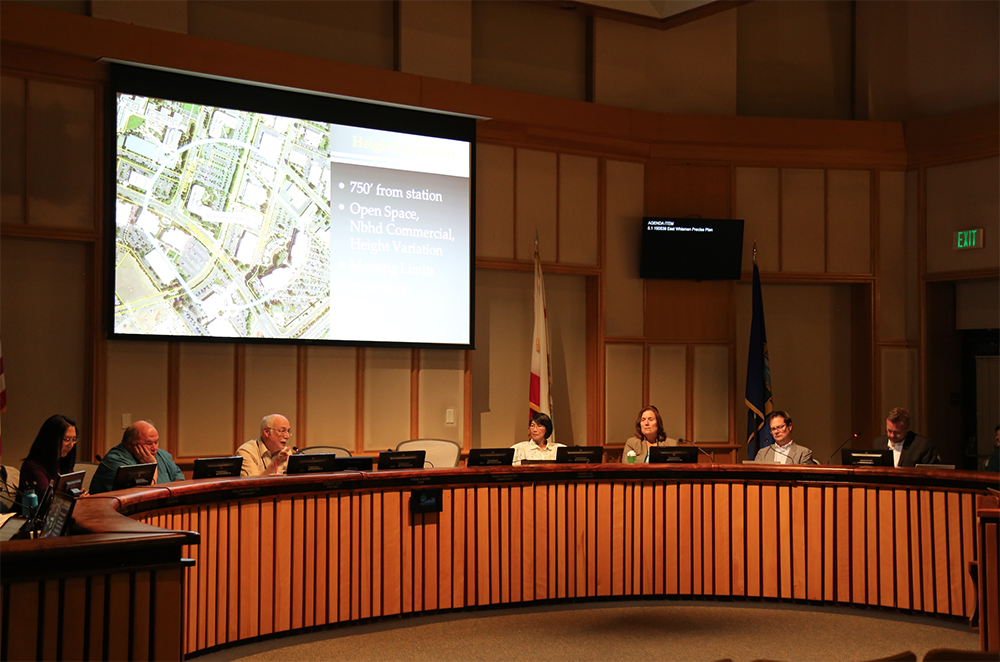

So it wasn’t the Superfund site that concerned the Environmental Planning Commission at this meeting, but instead, the new height allowances for office development.

“After all, this is Mountain View and many people would like to still see the mountains,” Commissioner Margaret Capriles said. Commissioners Capriles and William Cranston spoke in favor of supporting small businesses and keeping the height limit at a maximum of eight stories.

If approved, the plan would demonstrate successful collaboration between multiple stake-holders for wide-scale change. To make that happen, there are some remaining pieces of the puzzle to fit together before the Nov. 5 vote.

First, interested developers have long been a part of the conversation as they navigate how much the city can dictate while still making their projects possible. Real estate developers, Summerhill and Miramar, submitted letters to the Environmental Planning Commission to emphasize their needs. John Hickey of Summerhill presented at the commission that night, saying that as is, the plan’s unequal benefits for developers disincentivizes their involvement and “undermines one of the council’s key goals for the precise plan, which is to support residential development.” He and Miramar representatives are advocating for more standardized benefits for developers.

One such development program directly supports the Los Altos School District. The district owns land in East Whisman, and they will benefit financially to the tune of an estimated $79 million by transferring those rights to the current slated developers, including Summerhill and Miramar. These funds will go towards the district’s plans to buy land near San Antonio for a new school — 11.5 acres of land that costs $155 million in total.

Creative sources of funding are essential for the District these days — not only because their planned new school is on especially expensive land, but because “schools in CA are funded very poorly compared to the rest of the nation. We were at one point in the top 5, now we’re in the bottom 10 percent in terms of funding level for kids,” said Randy Kenyon, assistant superintendent of Los Altos School District.

In the next few weeks, planners will be working hard to balance the precarious number of interests.

“There’s still a lot to do,” Anderson said.