People were lying on the ground at a park in Palo Alto. Some needed splints, while others needed bandaging. Dan Melick was one of them. Volunteers were going around, doing a triage of the people and helping the injured. It was a scene from a disaster. This time around, however, it was simulated.

Melick recalled the day when he signed up to serve as a “victim” for one of the exercises for the Community Emergency Response Team (CERTs). It was afterwards when he decided to sign up to become a CERT himself.

“I’d rather be not a victim. I’d rather be on the other side, where I’m going and treating people,” he said.

Melick is not the only one interested in emergency preparedness and response. More people are asking how to prepare for emergencies — whether it be the next earthquake, wildfire or nuclear bomb threat. And these are not just the doomsday preppers. Articles on how to pack your own emergency kits proliferate the internet, and online shops sell ready-to-go kits anywhere from $25 to a couple of hundred dollars.

Emergency preparedness and response in Palo Alto

Palo Alto has been quiet in the recent years: no major earthquake has hit the area since Loma Prieta in 1989 and the 1998 flood affected only a small part of the city, and no major crimes, such as terrorism, has been reported. But the city should not be complacent, as preparedness is key to building resilience during crisis and emergencies, according to Nathan Rainey, Emergency Services Coordinator of Palo Alto.

For Dueker, having a network of volunteers and educating the community is important. A volunteer network could fill in the gaps and provide people assistance for less pressing problems.

As listed in the city budget, the Palo Alto Police Department is authorized to have a staff of around 158 full-time first responders (including both sworn law enforcement officers and non-sworn staff who provide support through other services). In addition, 115 full-time first responders who are sworn in can staff the Fire Department and three for the OES.

Dueker has a caveat: “Not all of these positions are filled – recruiting is difficult.”

“The government has limited resources, so first responders have to focus on the most critical problems,” said Rainey. “Folks in the neighborhoods probably will make the most difference when there is a large need.”

The ESVs of Palo Alto

One such program is Palo Alto’s Emergency Services Volunteers (ESVs), which has its roots in the city’s CERT program, Neighborhood Watch and the Palo Alto Neighborhoods (PAN), an independent umbrella group supporting the neighborhoods in the city.

“Some years ago, when I was running the homeland security unit in the police department, I was asked to meet with some of the PAN leadership to see how our then-defunct Neighborhood Watch program and other city volunteer efforts could be aligned,” recalled Dueker. “The output was this partnership between PAN and the city that lead to the ESV program.”

Aside from supplementing the resources of the first responders, ESVs also stay in touch with the people in their jurisdiction, thus providing a framework for neighbors helping their neighbors.

The ESVs encompass all the city-sponsored emergency preparedness volunteer programs: the Block Preparedness Coordinators, Neighborhood Preparedness Coordinators, CERT volunteers, Amateur Radio Emergency Services (ARES) and Radio Amateur Civil Emergency Services (RACES). More than 700 volunteers, including those who work in Palo Alto but live elsewhere, are active members of Palo Alto’s ESV program.

Of the ESVs, 407 are registered as block coordinators, while 39 are in charge as neighborhood coordinators. Block coordinators keep an eye out (and ear open) for the people on their respective blocks. They are tasked with getting to know their neighbors and sharing information on emergency preparedness. On the other hand, neighborhood coordinators are the main point persons for the BPCs and CERTs in the area.

Ann Crichton, the neighborhood coordinator for a portion of midtown Palo Alto, explained, “What I do is, I act as a central spoke for communications and then communicate whatever needs to be escalated to the fire stations or to the Disaster Operations Center.”

While the coordinators organize and report on issues in their areas of jurisdiction, CERTs are volunteers who are trained in disaster preparedness, basic medical treatment and search and rescue. They first respond to problems in their own neighborhoods, as seen fit by their coordinators, but could also be deployed citywide if needed.

According to Rainey, it is the block coordinators and neighborhood coordinators that make Palo Alto different from other cities in Santa Clara County. While other cities rely on their CERTs to coordinate emergency response in their blocks and neighborhoods, Palo Alto found that having coordinators on the ground reinforces the value of neighbors helping neighbors.

These teams in the neighborhoods are supported by 75 amateur radio volunteers from both the ARES and RACES programs. These volunteers help improve communications between the coordinators on the ground and the coordinators with the city, in times of disasters. Mainly composed of hobbyists, radio volunteers help fill communications gaps when networks are not functional.

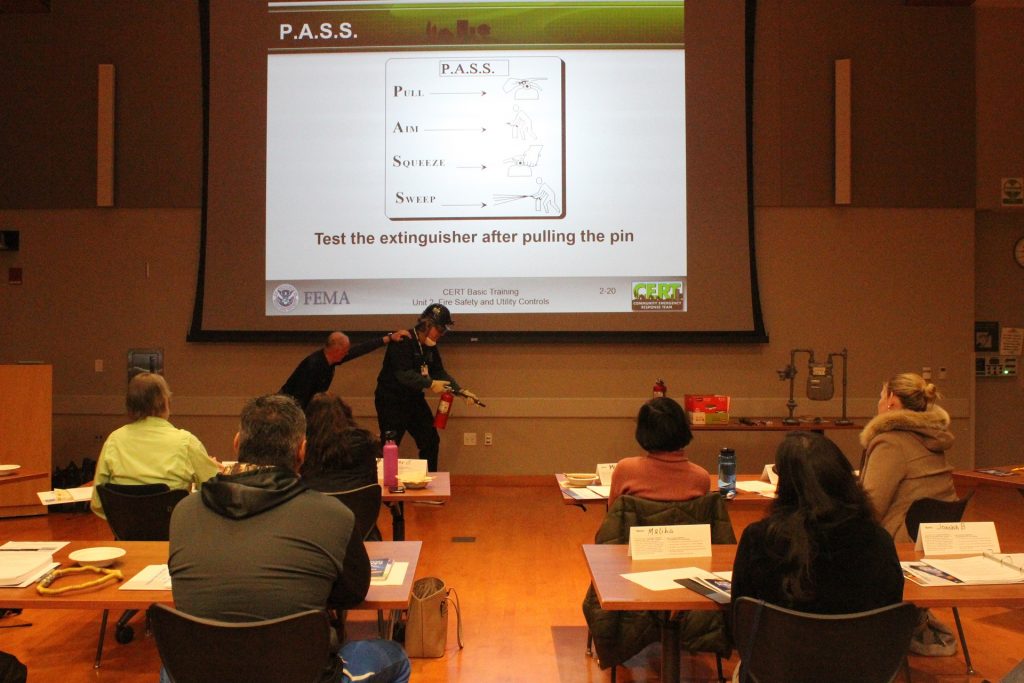

Skills: Learning and using, instead of losing

Anyone over 18 years old, who either lives or works in Palo Alto, are encouraged to serve as volunteers. The city offers training courses for people who want to serve as either block coordinators or CERTs. A block coordinator certification class is usually three hours long, and is held once every quarter, according to Rainey, while CERT classes are held over the course of three weeks, with a final culmination activity at the end of the course. The spring classes were held at the Mitchell Park Community Center during Monday and Wednesday evenings last March 5 through 21. Twenty-one students graduated the course at their culminating exercise on March 24. Fall classes for this year will start September 4.

Exercises, both neighborhood-wide and city-wide, are also regularly scheduled to make sure the volunteers get to practice what to do in case of disasters and how they should communicate with one another. Without practice, volunteers are more prone to forget what should be done. Melick, one of the four CERT instructors in Palo Alto, is a big believer in practice.

“You learn a skill, you use it or you lose it,” he said.

Crichton recalled before she became an ESV, when they had to put out a fire in her friend’s kitchen. Neither knew where the fire extinguisher was – it turned out to be outside their apartment door.

“I really know from personal experience, that if you don’t practice, you really don’t know where stuff is in an emergency,” Crichton said.

For her, just having a sense of what people would do in particular circumstances could make a big difference.

It is not only the volunteers who need to know what to do during an emergency. According to Rainey, coordinators also have the task of looking out for their neighbors and informing them about emergency preparedness. The block coordinators are essentially seen as the eyes and ears in the small communities, thus capitalizing on the local people, since neighbors are usually the first ones on the scene is something happens.

With the establishment of the ESV program, the city was able to manage the volunteers and set up a chain of command to be followed during disasters and emergencies. CERTs, who always operate in teams of at least three people, appoint team leaders. These leaders along with the block coordinators report to their respective neighborhood coordinators. The ESV Division Operation Center coordinates efforts in the neighborhoods and reports back to the city’s Emergency Operations Center manned by the OES.

The ESV Policy Manual does point out that: “ESVs are always subordinate to any sworn officer (police or fire) who arrives on scene.”

Forming an ESV program in Palo Alto and beyond

Annette Glanckopf, co-founder of PAN and also a neighborhood coordinator, has been involved in emergency preparedness in Palo Alto for many years. She recalled that 9/11 largely served as the catalyst for the formation of a group of volunteers to assist the neighborhoods in the city. In 2004, Palo Alto declared emergency preparedness as one of the key city priorities and remained so for a couple of years afterwards.

The city’s OES wasn’t established until 2011, when the city decided to put the CERTs (which had been under the Fire Department), PAN and the amateur radio volunteers under one office and one program. So far, many of the comments regarding the program have been positive.

Melick said, “We in Palo Alto, I think, have done a really, really good job compared to a lot of the other cities. We have one of the most complete and well-documented programs.”

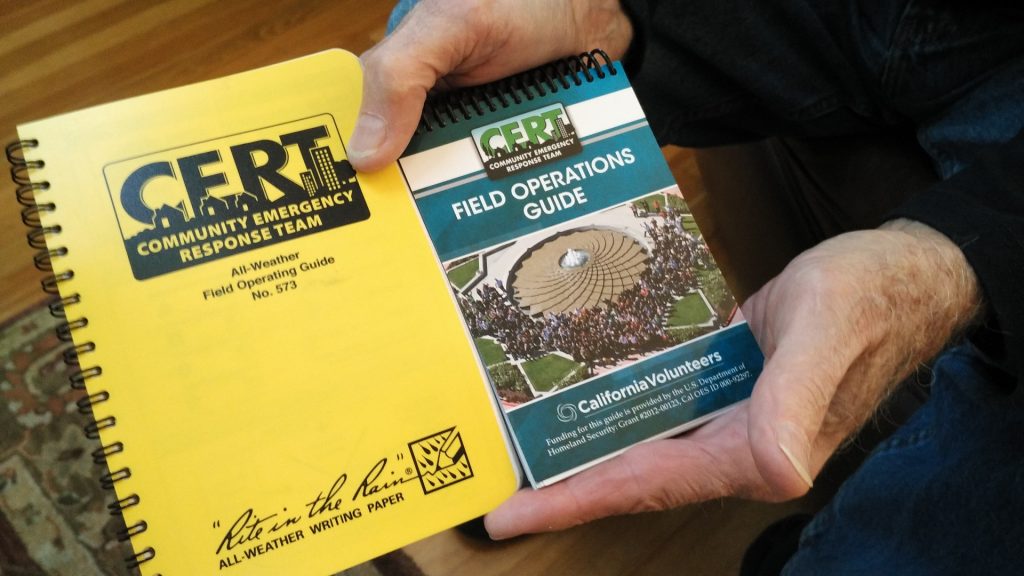

He and Glanckopf had drafted the field operating guidelines for the Palo Alto ESVs.

Glanckopf, who still came across as passionate about emergency preparedness over the phone noted that the ESV program is “probably the best program that you can do structurally”. It is to Palo Alto’s testament that other communities in Santa Clara County are looking to develop similar programs.

In 2014, the neighboring city of Los Altos started training volunteers under their Block Action Team (BAT) program, according to Sherie Dodsworth, the volunteer program manager.

“People that know each other will take care of each other in times of emergencies,” said Dodsworth. Inspired by Glanckopf and Palo Alto, and the best practices from the cities of Burlingame and Cupertino, the BAT program also aims to support city-employed resources in times of major disasters.

Santa Clara County’s OES also acknowledges the importance of having neighborhood-based volunteers in times of major regional disasters. The Federal Emergency Management Agency recommends that residents should plan to fend for themselves for the first 72 hours, as the first responder teams would be needed to attend to the more critical emergency situations.

“By having volunteers in the neighborhoods, if someone does need first aid or another type of assistance that a CERT volunteer can provide, then that would be immediately available to them,” said Patty Eaton, public information officer of the county’s OES. “I think it is a really important part of the chain of response services. The volunteers are close, they know the neighborhood, they’re organized, they’ve practiced, trained, so they’re tremendously valuable in an emergency situation.”

Keeping volunteers involved and improving

Having a well-structured ESV program, which grows by about 100 volunteers per year, is not without its problems though. For Rainey, getting volunteers to prioritize ESV trainings and exercises is one challenge, especially since volunteers need to maintain their skills. Knowing and remembering what to do during an emergency is important.

“Neighbors helping neighbors is a proven best practice,” said Rainey, during one of the CERT classes this March. He then went on to explain that local neighbors are usually the first ones on the scene, and it is therefore important for them to know what to do if they ever wanted to help in cases of emergency.

For Rainey, a worse thing that could happen during a crisis is when volunteers who do not know what to do, get into trouble themselves and create more problems.

“Don’t become a victim but become a resource – and you can become a resource by training,” he said. As the OES is able to provide the right training, volunteers are highly encouraged to participate in the exercises and refresher courses.

Melick agrees with him. “That’s probably what I would say is probably the biggest challenge is keeping all the people that you’ve trained active,” he said. “That’s the one thing that I’m hoping will get better. And we try to teach that in all the classes: stay involved.” There will never be enough registered volunteers, since every hand helps, according to Rainey.

At the end of the day, the ESV program not only helps communities prepare for disasters, but also builds relationships within the communities, as noted by both Crichton and Glanckopf.

“I guess I just love the program because you get to know your neighbors. That’s like the best part of it,” Crichton commented. “This is a topic that resonates with almost everyone,” Glanckopf also said. “Everyone says emergency preparedness is important, but less than 10 percent are actually prepared, according to a Red Cross report.”

Crichton does have some tips for those who want to start doing something: “Don’t try to do too much too fast. It’s super easy just to sit down and say what would I do in an emergency and write down telephone numbers. Start there.”