5 quick things you need to know about the conflict

CATALONIA — Almost half of Catalonia wants to secede from Spain. Catalonia, a region the size of Maryland, was in the news late last year when police beat protesters in Barcelona — the region’s capital — after what the Spanish highest court said was an illegal vote for independence.

After the referendum, Catalonia’s regional government declared independence. The Spanish central government — which vehemently opposes all secession moves of its most wealthy region — said the move was unconstitutional, stripped the local administrations of their powers and called early elections.

The former regional president Carles Puigdemont left the country and is fighting extradition from Germany after refusing to be prosecuted in Spain on charges of rebellion and misuse of public funds. And in late May, Catalonia’s parliament elected separatist Quim Torra as president.

On June 2, his new pro-independence regional cabinet was sworn in, regaining control of Catalonia from the central government. Only a few hours earlier, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez replaced Mariano Rajoy, who was voted out amid a corruption scandal affecting his conservative party. Sanchez, a socialist, says he’s more willing to talk to pro-independence forces than his predecessor.

Here are five things you need to know about the most important Spanish political crisis since the country transitioned to democracy after the death of dictator Francisco Franco in 1975.

1. Why does Catalonia want to be independent?

Catalonia is one of Spain’s 17 autonomous regions, which have their own regional governments but still depend on the central government for budget allocation and federal regulations. Catalonia is one of the wealthiest regions, accounting for 16 percent of the national population and almost 19 percent of Spanish GDP. The region’s capital city is Barcelona, the number one destination for tourists in Spain. More than 19 million international tourists visited Catalonia in 2017 — the same number as visited Canada.

When the 2008 financial crisis hit Spain, Catalonia was especially affected after the central government raised taxes. Since the region is wealthier than others, they had to pay a higher portion of the total taxes, pro-independence forces said. The regional government said the wealthy region was propping up the poorer rest of Spain.

Separatist forces have been lobbying for independence for decades.

But the key moment came in 2010. Spain’s Constitutional Court declared a 2006 Catalan statute that granted more powers to the region unconstitutional. Among other things, the ruling struck down attempts to place the Catalan language above Spanish in the region. It also defined references of “Catalonia as a nation” as incompatible with the Spanish Constitution, which states that there’s only one nation: Spain.

From that point, experts say, separatists decided to use a more direct way for independence: a referendum.

2. Why did police beat voters in October? Why did public officials get arrested?

According to the 1978 Spanish Constitution, the country’s territory is indivisible. In October, pro-independence political parties went ahead and held a referendum in the region to secede from Spain, a move declared illegal by the Spanish Supreme Court.

The Spanish central government sent police to try to stop people from voting in this referendum. Police used force, and hundreds were wounded.

After the vote — in which 92 percent supported independence but partly because those opposed to secession boycotted — the regional government decided to unilaterally declare Catalonia’s independence, in violation of the Spanish Constitution. This caused some of Catalonia’s leaders to be jailed for disobedience. The region’s former president, Puigdemont, along with other regional leaders, fled Spain.

The central government dissolved Catalonia’s parliament and called an early regional election for December 2017. Between December and May political parties tried to negotiate and form a government. After months of political uncertainty, Torra was sworn in as regional president on May 15, and his cabinet took office on June 2.

3. Who are the parties involved?

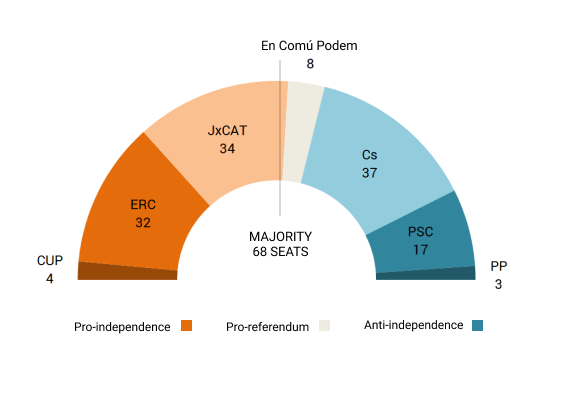

Pro-independence political parties — Junts per Catalunya, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya and Candidatura d’Unitat Popular — won only 47.5 percent of the popular vote in the regional elections. However, because of the distribution of electoral districts, that translated into 70 seats in the 135-seat Catalan parliament, which gave separatists a slim majority.

Separatists attract voters of all ages, social groups and political beliefs. The three parties, each one with a different ideology (from center-right to anti-capitalist left), use independence as their main point of agreement. That’s why they decided to form Catalonia’s government together, even though they don’t share many economic and political beliefs.

Other parties include anti-independence political parties — Ciutadans, Partido Socialista Obrero Español and Partido Popular — and an intermediate option, En Comú Podem, which argues that the region should have the “right to decide” through a legal referendum.

4. Who’s winning?

Around 48 percent of Catalans would be in favor of an independent Catalonia, and 44 percent would be against, according to an April survey conducted by Centre d’Estudis d’Opinió, an organization that reports directly to the regional government.

Even though a majority of the voters in the regional election chose anti-separatist political parties, pro-independence forces rule the parliament and hold the presidency.

At the same time, separatists are trying to win international attention and sympathy for their cause. Some of their leaders left the country after Spain issued extradition orders for some separatists, charging them with rebellion and misuse of public funds for holding the illegal referendum.

In early June, a German court applied for the extradition of former regional president Puigdemont to Spain.

5. Will Catalonia become independent?

Maybe, but not for now. There are two possible options in the medium to long-term, according to experts.

Making concessions

The first solution would involve the central government making efforts to accommodate Catalonia’s distinctive features. This would likely involve a Spanish Constitutional reform or the writing of a new, legal and consented statute for the region.

A negotiated and legal referendum for independence

The second option would revolve around the holding of a constitutional referendum for independence of Catalonia. Pro- and anti-independence forces would participate in a political campaign that would result in a legal vote, similar to the referenda held in Scotland in 2014 and Quebec in 1995. In both cases, voters decided to remain part of the United Kingdom and Canada, respectively.