SAN FRANCISCO — When Sean Moore, a 43-year-old with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, was shot twice by a San Francisco police officer on Jan. 6, it triggered a police department investigation, a town hall meeting and months of headlines, as well as serious medical problems and criminal charges for Moore.

The middle-of-the-night confrontation, which took place on the stairway leading to Moore’s front door, was the San Francisco Police Department’s first officer-involved shooting of 2017 and the first ever to be filmed on body cameras.

Handling incidents involving mentally ill people is a growing challenge for the department. Encounters are so common that when two officers were sent to Moore’s home at 3:51 a.m., San Francisco police had already received four calls for people classified as “mentally disturbed” or suicidal, and they would respond to 52 more before the day was over.

Calls labeled mentally disturbed vary widely but can include a person acting strangely in a public place or walking down the middle of street, a family member needing help transporting a mentally ill person to the hospital and someone experiencing a psychotic break.

The department gets about 15,000 mentally disturbed and suicide-attempt calls per year. A tiny fraction result in officer-involved shootings — last year, officers shot and killed two people who showed signs of mental illness. But while incidents like shootings and hours-long standoffs grab the public’s attention, interacting with the mentally ill is a daily, even hourly, duty for San Francisco police.

A 2010 report on the SFPD’s workload related to the mentally ill found that an individual officer averaged 3.5 encounters per shift, and 10 percent of the department’s time in the field was spent handling mental-health incidents. The department and other city agencies continue to grapple with how best to handle those incidents and keep them from getting to the point where officers use deadly force.

“Personally, I had absolutely no idea that this was going to take up such a large component of law enforcement,” 18-year SFPD veteran Sgt. Laura Colin said. “I really thought it was more enforcing laws when I first came in. As you quickly build time in this department, you realize that mental health is huge. And a large component of what we do is dealing those struggling with some sort of mental health, behavioral crisis, things like that.”

5150 holds on the rise

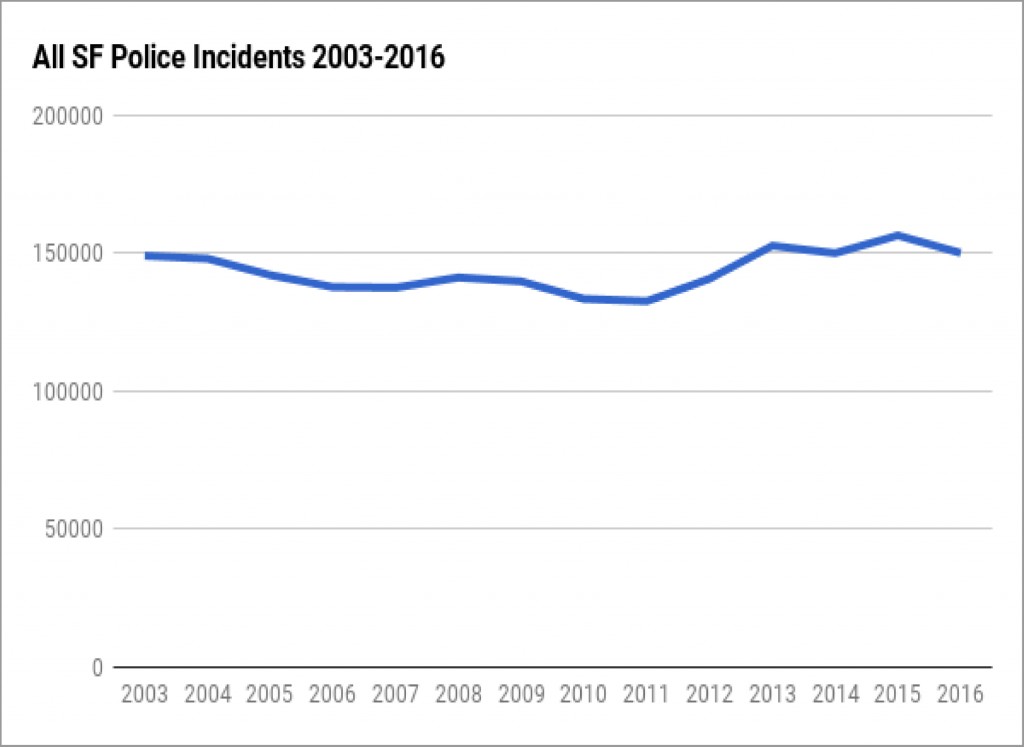

Tallying calls for service doesn’t necessarily capture the full scope of the issue because mental-health calls can be hard to classify. Often, a call will be dispatched as something seemingly unrelated but snowball into a mental-crisis incident. The officers who went to Moore’s Oceanview residence in January were responding to a call for a restraining order violation.

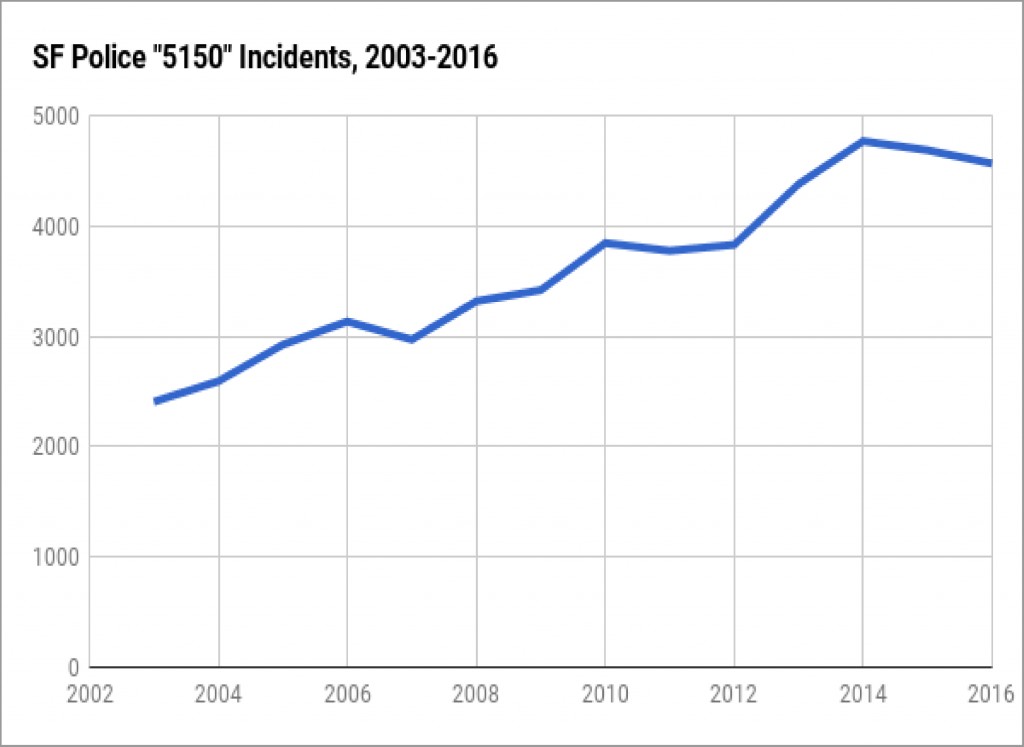

One type of incident that is easier to count, and involves people in a serious state of crisis, has been increasing for years. Incidents referred to as 5150 holds — named after the section of the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act that made them part of California law in 1967 — are when a person is put under a 72-hour psychiatric evaluation because he’s a danger to himself or others or is gravely disabled. According to San Francisco’s police incidents database, they’ve increased 16 percent since 2010 and nearly 50 percent since 2003. In 2016 alone, officers initiated 4,566 holds.

There’s no conclusive answer for why they’ve increased. But a lack of mental health services can lead to mentally ill people encountering police.

“We have in this country, for a long time, been underfunding and cutting services,” said Dr. Giff Boyce-Smith of the National Alliance on Mental Illness’ San Francisco chapter. “So you have a schizophrenic who should’ve been diagnosed by age 16 or 17 and is instead diagnosed at 33 when he’s on his way to a lifetime prison sentence.”

Boyce-Smith pointed to Governor Ronald Reagan’s policy changes in the late 1960s as a catalyst for an increase in what he calls the “criminalization of the mentally ill.”

Reagan signed the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, ending indefinite, involuntary hospitalization of people with mental illness in California. Helynna Brooke, executive director of the San Francisco Mental Health Education Funds, said funding for the care of people released or diverted from hospitals never materialized.

The San Francisco Chronicle reported last year that Mayor Ed Lee said the city needs hundreds more psychiatric beds to meet demand.

Brooke noted that mental illness is often interconnected with another prevalent issue in San Francisco — homelessness. Even mentally ill people who receive treatment may struggle with maintaining housing, and in turn, the trauma that can come with homelessness may exacerbate their mental condition.

Time and distance

Since 2011, the SFPD’s philosophy for interacting with people in mental crisis has been centered around the Memphis Model of Crisis Intervention Team training, which emphasizes de-escalation and “time and distance” — slowing down and giving the mentally ill person space.

Officer Robert Rueca, who is CIT-certified, said the approach includes “trying different ways of talking to people instead of escalating the situation and making the person more aggravated.” He added that officers can be “more effective by showing how you understand, and (trying to) help them through that situation.”

This year, the department is pushing to put all officers through a new 10-hour training course, and it plans to have everyone complete the full 40-hour training in four years, according to CIT Coordinator Lt. Mario Molina. Currently, about one-third of officers are fully trained.

When officers can successfully de-escalate a situation, they have limited options from there. Those who don’t qualify for a 5150 hold and haven’t committed a crime can be taken to the city’s Dore Urgent Care Center for treatment, but only if they’re willing to go.

Jim Dudley, who retired after 32 years with the SFPD, said when he couldn’t take someone for treatment, he was often “left with the awful feeling that I was going to get a call to go right back, and it could be worse when I get back.”

‘They’re escalating the situation’

Officers Kenneth Cha and Colin Patino, who responded to the call at Moore’s home in January, were not CIT-certified. Moore’s lawyer, Deputy Public Defender Brian Pearlman, said that led to the shooting.

In police body camera footage, Moore appears irritated when the officers arrive at his door, and, standing behind his closed gate, he repeatedly tells them to leave, frequently using profanities.

At one point, after Moore told them to get off his stairs, one officer asked, “Or else what?” Moore said, “Or else I’ll remove your a__,” and the officer responded, “Are you threatening us? You just threatened us.”

About four minutes later, Moore opened the gate, was pepper sprayed and grabbed paperwork from an officer. Eventually, there was a physical altercation, and Cha fired two shots.

“You can see in the video, they’re escalating the situation constantly,” Pearlman said. “They’re not minimizing it. And if an officer showed up that was Crisis Intervention trained, there would have been a very different response that would’ve occurred.”

Pearlman asserted that after initially speaking to Moore, the officers had no reason to arrest him or remain on his property. He added that audio picked up by a body camera some time after Moore was shot shows an entirely different interaction with an officer. Pearlman said a CIT-trained sergeant arrived and calmly tried to convince Moore to leave the house. Moore was calm but still didn’t want to come out, so the officer gave him some space.

“It’s just, you saw the huge disparity in how someone who is Crisis Intervention trained dealt with the situation and someone who wasn’t,” he said.

First contact: dispatchers

Before any officer shows up at the scene of an incident, emergency dispatchers must quickly gather information and help decide who should respond. When the U.S. Department of Justice conducted an assessment of the SFPD in 2016, it found the police needed to improve protocols for dispatching CIT officers and collect more data about mental-crisis incidents.

Robert Smuts, the deputy director of the Department of Emergency Management’s Division of Emergency Communications, said his staff collaborated with the police department on policy changes that were introduced this March.

When a dispatcher answers a call involving mental health issues, he or she can dispatch it as a crisis response call — meaning a team of four to five CIT-certified officers respond — if it meets specific criteria.

Operations Coordinator Janice Baldocchi said a dispatcher must receive detailed information about the situation, such as “my child is psychotic, off his meds, pacing and saying he wants to kill people.”

If the information is more general and less urgent — someone is depressed or a passerby reports a person acting erratically but not threatening anyone — Baldocchi said it would be dispatched as a mentally disturbed call. The responding officer may or may not have CIT training.

The decision doesn’t just fall on dispatchers. A crisis response can also be initiated by a sergeant at the scene.

Last year, a crisis response was dispatched 568 times — 556 for calls labeled mentally disturbed and 12 for suicide-attempt calls. Through the first four months of 2017, there was a total of 108.

As with the Moore shooting, officers don’t always know the person they’re dealing with has a history of mental illness. Baldocchi and Smuts said dispatchers can look up call history for an address to see if there was a previous crisis response or mentally disturbed call.

But there’s no database of addresses or people involved with past mental-crisis incidents or system that would automatically alert a dispatcher to a past incident.

Molina, the CIT coordinator, said the department is working toward more complete and efficient data collection. NAMISF has been assisting with that process, and Boyce-Smith hopes it leads to data that can inform the department’s operations.

‘There’s a commitment’

Molina said the department is committed to getting to the point where every interaction with a mentally ill person will involve a CIT-certified officer, because all officers will be certified.

“It takes a lot of planning on how we’re going to to do this, but there’s a commitment that we’re going to get it done,” he said.

Pearlman, the lawyer who defended Moore, insists it’s not happening fast enough.

“I feel like they’re not making it enough of a priority right now,” he said. “I mean, people should not be on the force if they’re not trained. There’s just too much ability for these situations to go really bad really quickly.”

Pearlman also criticized the way the department investigated the shooting, saying the main goal was to protect Officers Cha and Patino.

Moore originally faced 10 criminal charges, including assaulting an officer and battery with injury. He was released from custody in early May, and all charges were dropped soon after. He expects Moore’s family to file a civil suit.

“Mr. Moore’s mother’s big concern is she doesn’t want this to happen to anybody else,” Pearlman said, adding Cleo Moore “doesn’t want to see other people get hurt because of police officers’ lack of training.”