For some Marcy Orendorff’s painting, “House of the Broken Hearts,” was eerie. Others found it enlightening. No one had yet called it educational.

Parents physically fighting in the kitchen, sister and brother crying in the foreground: the painting depicted a dysfunctional childhood.

“I saw my father beat my mom. I saw my mom go hang out in bars,” Orendorff said in an interview, “I didn’t know how to say that it was wrong. I just lived that way.”

In her 30s, she began painting at the suggestion of a friend, and her repressed emotions resurfaced.

The painting hung in her open studio in Napa, when it caught the eye of a six-year-old boy.

The child approached the painting, gasped and said: “Oh, does this happen at your house too?”

This incident spurred Orendorff to use her art to teach children basic social and emotional skills that they don’t always learn at home. She is one of many artists and art teachers in the San Francisco Bay Area who endorse Social Emotional Learning (SEL), a progressive approach to education aimed at enhancing emotional intelligence and specifically designed for children.

Social and Emotional Learning-driven art is emerging in districts across the Bay Area.

On Nov. 16, the Institute For Social and Emotional Learning (IFSEL) demonstrated what art and SEL can do when combined, in a one-day workshop at Woodside Priory School in Portola Valley

“The kinesthetic and the visual, the touching, the doing, the molding and moving are very important as we go into this world of social and emotional learning,” said Janice Toben, managing director and cofounder of IFSEL.

Parents and teachers who participated in the workshop were invited to map feelings in Venn diagrams, act them out with body language and nonverbal communication, and shape them into wire sculptures.

Adam Siler, the dean of residential life at Woodside Priory School and a participant at the workshop, used the wire to express his feelings of helplessness and inadequacy at work.

“You guys started working on your wires about seven seconds into this activity,” said Siler turning to face his colleagues. “This is actually how I feel as a first-time manager”.

He then pointed at his zigzagged wire: “Look at this, guys. I’ve accomplished nothing.”

(Photo credits: Daniele Badocchi)

Another activity, “Layers of feelings,” encouraged participants to visualize overlapping and multidimensional emotions with folded black cardstock paper and oil-pastels.

“This is me stepping out of my comfort zone,” said James Pannell, a music teacher at Bentley School, who described struggling recently while judging a musical theater competition.

To visualize the discomfort he felt as a judge, Pannell daubed the cardboard with a penetrating bright green pastel. He then tore the sides of the rectangular piece of paper, to create an irregular, frazzled circle that emphasized that blazing center.

“The tears and the bright sharp colors on the very center and the outside are what’s uncomfortable… It’s not fitting to an 8 ½ by 11. It was torn out of it. It’s out of place.”

Toben said her main goal was to teach participants practical ways to integrate SEL in children’s daily lives.

“I am applying social and emotional learning with my children now,” said Ellen Rosenberg, a mother of three and director of the Manhattan Beach Education Foundation, “I was a tiger mom with my oldest son, but I am no longer.”

The arts “generate thinking that goes beyond routine tasks into other levels of problem-solving and imagination,” said Jamila Dunn, education director of Kala Art Institute in Berkeley, a program that engages local artists and art teachers in SEL initiatives.

In Berkeley, Luna Dance Institute teaches how to channel emotions into body language.

Oakland’s Destiny Arts Center uses art to help young students develop social skills.

Orendorff’s current venture in Benicia, “The emotional ecosystem,” employs simple imagery–such as butterflies and air balloons – to help children associate their emotions to pictures they understand.

However, the arts are just one facet of SEL’s growth.

The Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL), an organization based in Chicago which provides social and emotional leadership across the country, is leading school and district-wide systematic implementation of SEL, said Senior Advisor of Communications Hank Resnik.

SEL is determining new metrics of intelligence and changing the way teachers evaluate students in schools.

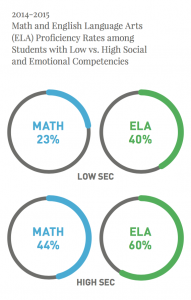

CASEL’s research shows that students with social-emotional skills do better in Math and English Language Arts, and are less likely to experience substance abuse, depression and eating disorders in their adulthood.

On May 18, 2017, California’s CORE districts – Fresno, Garden Grove, Long Beach, Los Angeles, Oakland, Sacramento, San Francisco and Santa Ana – released a set of social and emotional measures they plan to incorporate in Common Core Standards, the curricular academic skills students are expected to learn. .

“Oakland Unified District has been very intentional about its SEL implementation,” said Michael Funk, director of California’s Expanded Learning Division. “Other districts are starting to look at that, and learn from that.”

In Oakland alone, 20 elementary schools and all middle schools provide SEL instruction, following CASEL’s guide: the SELect curricula.

“There is a paradigm shift that is occurring with children,” said Orendorff, “… and I, as an artist, want to do my part.”