If you happen to walk by portable #2 at Cesar Chavez Academy in East Palo Alto, you’ll hear something that’s brand new to the school, and the entire school district: kids practicing the violin. The school began piloting a middle-school orchestra class last year and now 60 kids are learning violin, viola and cello. On a recent rainy morning, a group of eighth graders balanced violins on their shoulders and worked diligently to play scales along with their teacher, Sarah Azevedo.

“Let’s play together, and then we’ll do groups,” she said, lifting up her own violin. “One, two, ready, open G.”

The kids concentrated hard, staring down at their fingers moving along the strings. Sour notes were remarkably rare, considering that the students have only been playing for a few months. Azevedo gave lots of encouragement.

“That was awesome! Do it again!” she said. A transplant from Michigan, Azevedo is the kind of person who wears dangly earrings shaped like saxophones (her main instrument) and likes to add hip-hop drum beats to scales practice to shake things up.

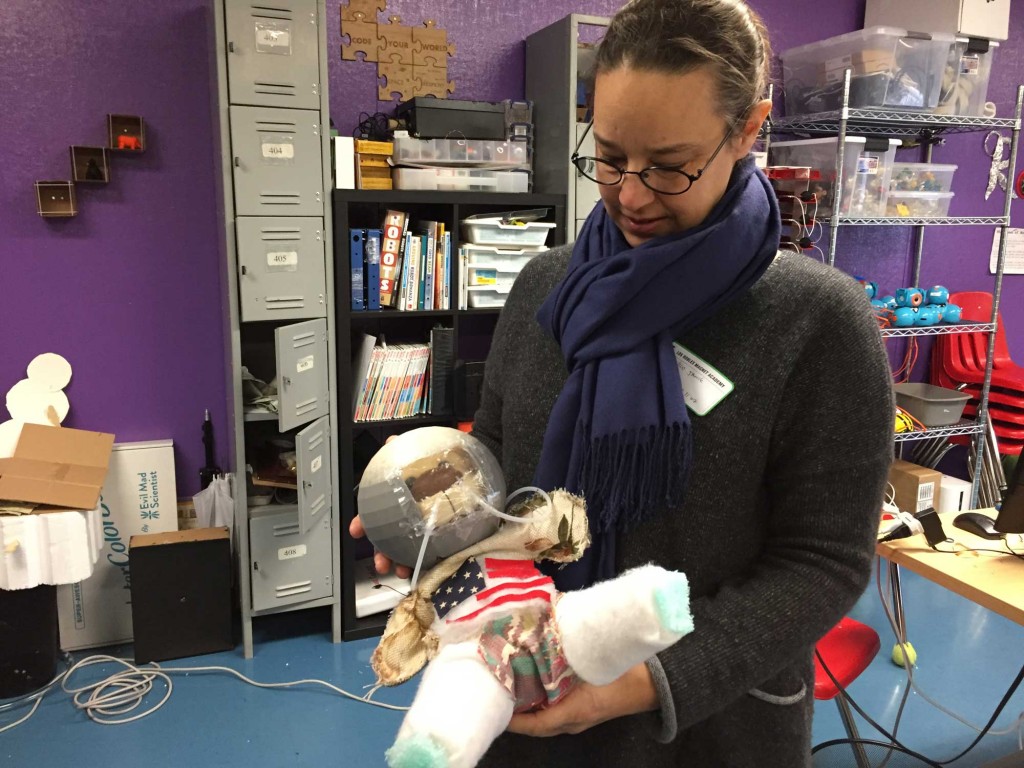

Adding orchestra is a big deal for the Ravenswood City School District, which for many years has struggled to find the funds for everything the district wants to provide. Now, the district has been able to not just add music classes, but also boost teacher salaries and create “makerspace” rooms in each school where kids can tinker and build robots. Roofs in long need of repair finally have gotten fixed.

That’s because more money from the state is coming in, in the wake of a 2013 shift in how California funds public schools. Gov. Jerry Brown pushed for a major change in the state’s school financing system to allow more local decision-making about how districts spend the money and additional funds for students in three targeted groups: kids from low-income families, English learners and foster youth. Ravenswood, which serves about 3,100 elementary and middle-school children in East Palo Alto and East Menlo Park, qualifies for even more money because it has a high concentration of kids in the targeted populations.

Reducing long-standing funding disparities between wealthy and impoverished school districts was one goal of the change. But is it working?

For Ravenswood, the extra money has helped, says Superintendent Gloria Hernandez-Goff. But the additional dollars haven’t been enough to erase disparities with nearby districts. Wealthy neighboring communities such as Palo Alto and Menlo Park raise so much money locally from property taxes that they can spend more than the funding formula set by the state, and they’re able to pay some of the highest average salaries for teachers in California. In 2015-16, the average teacher salary in the Palo Alto Unified School District was $101,408 and in the Menlo Park City Elementary District it was $101,064. In neighboring Ravenswood, the average was $68,730, according to figures compiled by the web site Ed-Data.org.

“We’re between Menlo Park and Palo Alto, both very highly paid school districts,” Hernandez-Goff said. “As a matter of fact, when they have openings, our teachers just – I don’t blame them – they just go there.”

To be sure, districts in affluent areas such as Palo Alto sometimes face their own budget problems. Right now, Palo Alto Unified School District is trying to identify more than $3 million in cuts for 2017-18 because of a shortfall in property tax revenue.

But nearby East Palo Alto has long been a pocket of poverty surrounded by extreme wealth. In the Ravenswood school district, 89 percent of students qualified for free or reduced-price meals in 2015-16. By contrast, in the Palo Alto Unified School District, where parents drop their children off in Teslas and BMWs and where the median home costs $2.5 million, 8 percent of kids qualified for free or reduced-price meals. Median household income in East Palo Alto is $52,012, according to the most recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau. In Palo Alto, home to companies such as HP and Tesla, median household income is almost three times that much: $136,519.

And an extreme shortage of affordable housing has left many families in the district in crisis, says Hernandez-Goff. She said school surveys show that more than a third of students in the district are homeless, which includes students sleeping in shared housing with other families, in motels, shelters, vehicles or outside.

“Almost on a weekly basis, we get additional homeless families and some of our families that did have a home, lose their homes,” Hernandez-Goff said. “We have kids sleeping in cars. We have kids sleeping in sheds. We have kids sleeping pretty much anywhere people can sleep – tents. I worry about them with the cold and the rain.”

Median rent in East Palo Alto in February was $3,432, according to data compiled by the real estate research firm Zillow. That’s twice as much as a minimum-wage worker in California would earn in a month working full-time.

Hernandez-Goff said that on top of the financial stresses, some immigrant families are worried about possible deportation as President Donald Trump orders increased enforcement of immigration laws.

“The hard part for me and the challenge for me is really trying to engage students in having schools be a haven for them – where they’re safe, where they want to be, where they feel really excited about learning,” Hernandez-Goff said.

So against that backdrop of families coping with multiple stresses, the state’s switch to the so-called Local Control Funding Formula doesn’t go far enough, she said. The switch has helped lift Ravenswood’s current expense of education per average daily attendance, a measure of per-student spending, to $15,578 in 2015-16 from $10,707 three years earlier, according to data from the California Department of Education.

By comparison, Palo Alto Unified spent $17,941 per student in 2015-16 and Woodside Elementary School District spent $25,901. To be sure, there are districts near Ravenswood that spent less per student. For example, Redwood City Elementary School District spent $11,543 in 2015-16.

Ryan Smith, executive director of The Education Trust-West, an advocacy group focused on closing achievement gaps for low-income children and students of color, said the fact that California is directing more money toward the neediest students is a big deal. But he said long-standing disparities between rich and poor districts still exist.

“It’s a good start, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that it washes all that out,” Smith said. “In fact, our own research has shown that it’s gotten closer but it certainly hasn’t erased the inequities we see in funding across the state.”

Test scores are one of the main gauges for assessing whether the state’s move to target more funds to needier students is paying off. So far, there are still big achievement gaps. For example, in last year’s California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP), 35 percent of kids categorized as “economically disadvantaged” met or exceeded the standard on the English language arts and literacy test in California. For kids who are considered “not economically disadvantaged,” 68 percent met or exceeded the standard.

“I would hope to have seen opportunity gaps begin to close after three years of the Local Control Funding Formula and we’re not seeing that necessarily in the research that we’ve done,” Smith said. “I’m hoping that at least in the next couple of years we start to see higher levels of achievement for those students we’re spending the money on. And if we don’t, I think we need to course correct as a state.”

Smith said it’s not just a matter of giving schools more money. He said what’s needed is to figure out a way to create a better system of getting districts to share best practices that have delivered results.

Even with the funding boost, test scores in the Ravenswood school district haven’t budged much. Last year, 19 percent of students exceeded or met the standard in the English language arts and literacy part of the CAASPP test. In 2015, 18 percent met or exceeded the standard.

And in the neighboring Menlo Park City Elementary District, scores are much higher. Last year, 82 percent exceeded or met the English language and literacy standard.

For a district like Ravenswood, the hurdles to overcome can seem daunting. How do you prepare kids for a test that requires familiarity with computers when many kids don’t have computers at home and some don’t have a home at all? How do you get kids to concentrate when they’re preoccupied with stress and upheaval at home?

Hernandez-Goff said she’s trying to tackle all of these things. The district has added laptops and improved Internet access in classrooms, boosted teacher salaries and added professional development and mentoring opportunities for teachers. Kids now have more access to music, art and science instruction. The district even serves warm dinner to kids in the after-school program. Hernandez-Goff plans to add washing machines at schools so parents can do laundry and take time to meet with other parents or volunteer in their kids’ classes.

“Our kids need a place that they can engage and be around adults and get help that they need and feel safe,” Hernandez-Goff said.

To achieve what she wants to achieve, Hernandez-Goff needs buy-in and participation from parents. California requires parent involvement in the budgeting process under the Local Control Funding Formula system, and every year since the change, Ravenswood has been holding meetings with parents to get their input on how they want the money to be spent.

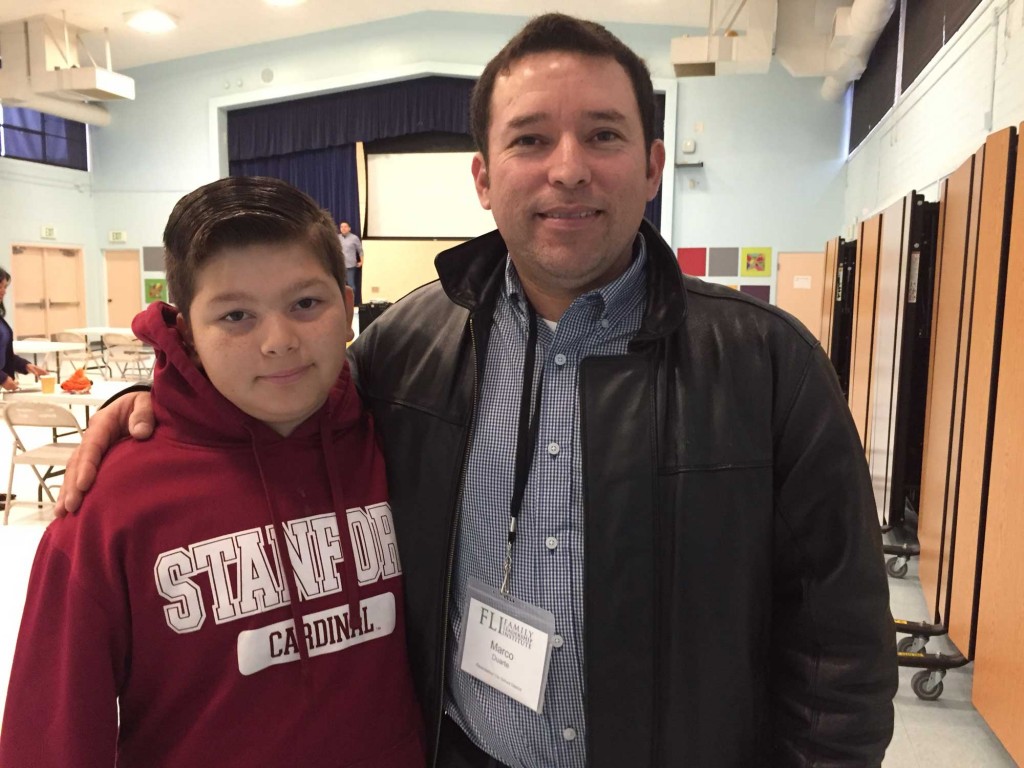

Marco Duarte, president of the District Advisory Committee and father of three kids in the Ravenswood district, said he’s seen an increase in parent involvement. From a personal standpoint, he said he’s pleased the district has added classes such as orchestra. His son, Noel, is in sixth grade and taking violin. Noel says proudly: “I’m at the top of the class.”

But Duarte says the extra money still isn’t enough – especially when it comes to teacher salaries.

“We have really good teachers that said, `I cannot live here because the rent is too high,’” Duarte said. “So they have to move out. And that’s a shame for us.”

Duarte said he knows parents who opt to send their kids out of the Ravenswood school district. More than 1,200 students from the Ravenswood district choose to attend school in other districts in San Mateo and Santa Clara Counties under a long-standing court settlement known as the Tinsley Voluntary Transfer Program intended to reduce racial isolation.

Hernandez-Goff said she initially wanted to end the transfer program but decided she first needs to concentrate on improving outcomes for kids in the Ravenswood district so parents want to send their kids there. And yet, she said it’s an uphill climb in part because of continuing financial disparities between her district and surrounding communities.

The state’s switch to the Local Control Funding Formula “is doing a lot to bring us out of that, but we’ve been in a hole. It’s not like we’ve been on the level playing field,” Hernandez-Goff said. “So it’s bringing us up, but we’re not really on the field yet. And I think it will take some time.”