The evening before the Nov. 8 election, Nisreen Baroudi, a deputy public defender in Santa Clara County, went to juvenile hall to speak with the kids held there. They were nervous about the election, but it wasn’t the same anxiety that gripped much of the rest of the nation. They were closely following Proposition 57, a law that would likely determine a significant portion of their future, if not their entire lives. The kids’ cases were pending direct file — meaning they were being prosecuted as adults — and they hoped that if Proposition 57 passed, they might have a chance to return to juvenile court and ultimately avoid adult prison.

Baroudi spoke with them about the proposition and joked with them, wanting to ease their fears.

“We said, ‘I know you have some anxiety, make sure you don’t get into any fights while you’re here in the hall. It’s going to affect your hearing,’” Baroudi recalled in an interview. “I joked with them that they should make a pact with each other: ‘I’m not jumping into a fight – not cause I’m a sucker – but because, hey dude, I’ve got a lot riding on this.’”

Before Proposition 57 passed, California district attorneys had the power to prosecute youth as adults. When a juvenile is tried as an adult, they are sent to adult criminal court and can end up in prison if found guilty, rather than in the juvenile justice system, which emphasizes rehabilitation.

Proposition 57 took the power to transfer youth into adult court, called direct file, away from district attorneys. The pressing question now is whether the law will apply retroactively — meaning that if a juvenile committed a violent crime before Proposition 57 passed, they would receive the same treatment as someone who committed the same crime after the election. Because the law made no mention of retroactivity, the decision is being made on a county-by-county basis.

In Santa Clara County, the District Attorney’s Office decided that the new law should apply retroactively to cases that are currently being direct filed, which Baroudi estimates will return about 40 youth being tried in adult criminal court to juvenile court. Santa Clara County was the first county in California to decide the law should apply retroactively.

“It’s giving the kids and the families hope, and it’s giving the judges power back to treat these kids as kids, if that’s the right thing to do. I think it’s a huge shift in the culture,” Baroudi said. “I’m seeing all smiles right now when I go to court.”

There is no statewide data as to how many cases are currently pending direct file. But experts estimate there could be more than 500 youth with pending direct file cases who would get the chance to return to juvenile court if every county agreed that the law should apply retroactively.

“The counties right now are all over the place,” Baroudi said. “I hope the other counties follow” Santa Clara’s lead.

Public defenders will need to decide how to use the law to challenge past convictions of youth who are already serving time in prison. In 2015, 492 youth were direct filed and sentenced to prison terms.

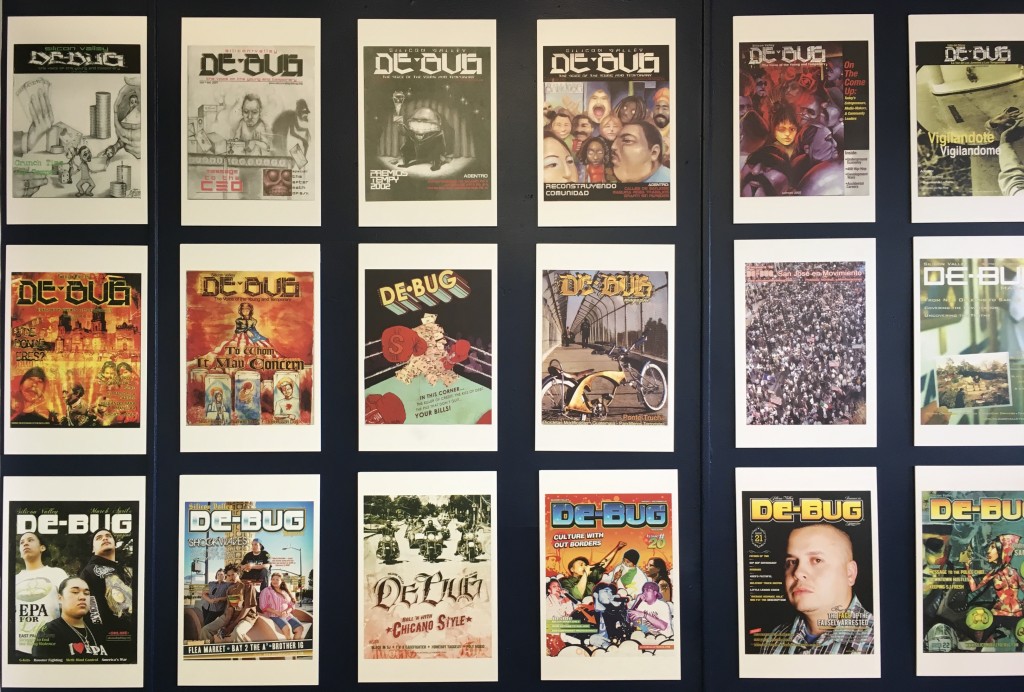

Charisse Domingo is a community organizer for Silicon Valley De-Bug, a media and activist organization based in San Jose. Domingo and De-Bug help the families of youth being direct filed navigate the legal system.

Domingo and De-Bug have been working with the family of Joseph, a 19-year-old being tried in adult court and facing up to 28 years in prison. Joseph was direct filed when he was 17. Joseph’s family was excited that Proposition 57 would help prevent other youth from facing time in adult prison, but they didn’t know if the proposition would help their son. But because the law is retroactive in Santa Clara County, Joseph is now back in juvenile court and could receive a juvenile disposition, which would mean that the longest sentence he faces is six years.

When Domingo called to tell Joseph’s father that he would be brought back to juvenile court, she could hear him start to cry over the phone.

“That was really exciting to be able to tell the families,” Domingo said. “It was everything they had really hoped for, and more,” Domingo said.

Every Sunday, the families that they work with meet in the De-Bug office. The families say the name of the loved one they are trying to help and then write the name on a list. When those individuals are released from prison or juvenile hall, they go to De-Bug and erase their own name off the list. They use what Domingo calls “the Eraser of Justice.”

“That erasing really represents the family being able to rally support around their loved one to bring them home,” Domingo said. “We always cry when we see it — everybody cries. But it’s really significant for the family that first walks in, because then they see there’s a finish line.”

Domingo said they have already seen the effects of Santa Clara County’s decision in other counties. The mother of a youth being direct filed in El Dorado County called De-Bug, asking if the retroactivity would apply to her son’s case. It didn’t apply directly, but De-Bug suggested that she tell her son’s attorney about what was happening in Santa Clara County.

De-Bug is working with her to create a social bio video of her son to present in court, which will include collected letters and photos from his family to show that his prospects at home would be more beneficial to him than being sent to prison. His public defender was able to point to Santa Clara County as an example of where Proposition 57 was being applied retroactively. The argument convinced the judge, and her son was granted a hearing to be considered to go back to juvenile court.

“It’s pretty exciting that the decision of this county can really affect a lot of people,” Domingo said. “People are excited. Because they know that the organizing and the support they did for their loved ones is affecting other people in an exciting way.”

Christopher Yuen is an adult public defender in Santa Clara County, representing a juvenile client who was direct filed into adult court. His client is 17 years old, and anxiously followed Proposition 57 through the election. The retroactivity of the law means that his client will be returned to juvenile court.

“I think it gave everybody a huge, huge glimmer of hope that maybe I can get a juvenile disposition,” Yuen said in a phone interview. “Maybe I can go to juvenile court. It’s a drastic difference between adult court and kids court.”

Yuen and Baroudi say that just because the youth are being returned to juvenile court, it doesn’t mean that the district attorneys won’t try to transfer them back to adult court. But even if this is the case, they would receive a full transfer hearing with a juvenile justice judge, which they were denied when they were direct filed.

“They’re not all going to be found fit [for juvenile court], and some of them will end up back in adult court. And my kid may end up back in adult court, but I would at least like the opportunity to fight for him to stay where he is,” Yuen said.

This story was updated at 3:55 p.m. PT on Dec. 16.