Facing rising operating costs, Caltrain is considering increasing fares and parking fees, a move that transit advocates warn risks worsening inequities in the Peninsula’s transportation system.

The plan would raise ticket prices by 50 cents, and hike daily parking fees from $5 to $5.50. Other passes would see equivalent price increases — a two-zone monthly pass would go from $126 to $137.80, for example. The hikes would raise an extra $8.3 million annually, helping to cover operating expenses that Caltrain projects will grow from $130 million this fiscal year to $163 million in 2021.

The proposal comes as more commuters choose Caltrain as a sustainable alternative to congested freeways. Yet while ridership has grown by 60 percent in the past five years, the train service lacks a dedicated source of public funding. That makes Caltrain heavily reliant on fare revenue to keep trains running — even if those high fares price out lower-income riders.

“To operate our system and provide the service that our customers have come to depend on, we need to explore increasing revenues from the farebox,” said Caltrain spokesman Seamus Murphy. Otherwise, “we’re having a conversation about cutting service at a time when we should be talking about increasing it.”

Most public transit services in the U.S. are largely funded through taxes, keeping ticket prices low. The idea is that since transit provides a range of public goods that benefit everyone — reduced congestion and pollution, increased economic activity, mobility for residents without cars — all taxpayers should contribute to their costs.

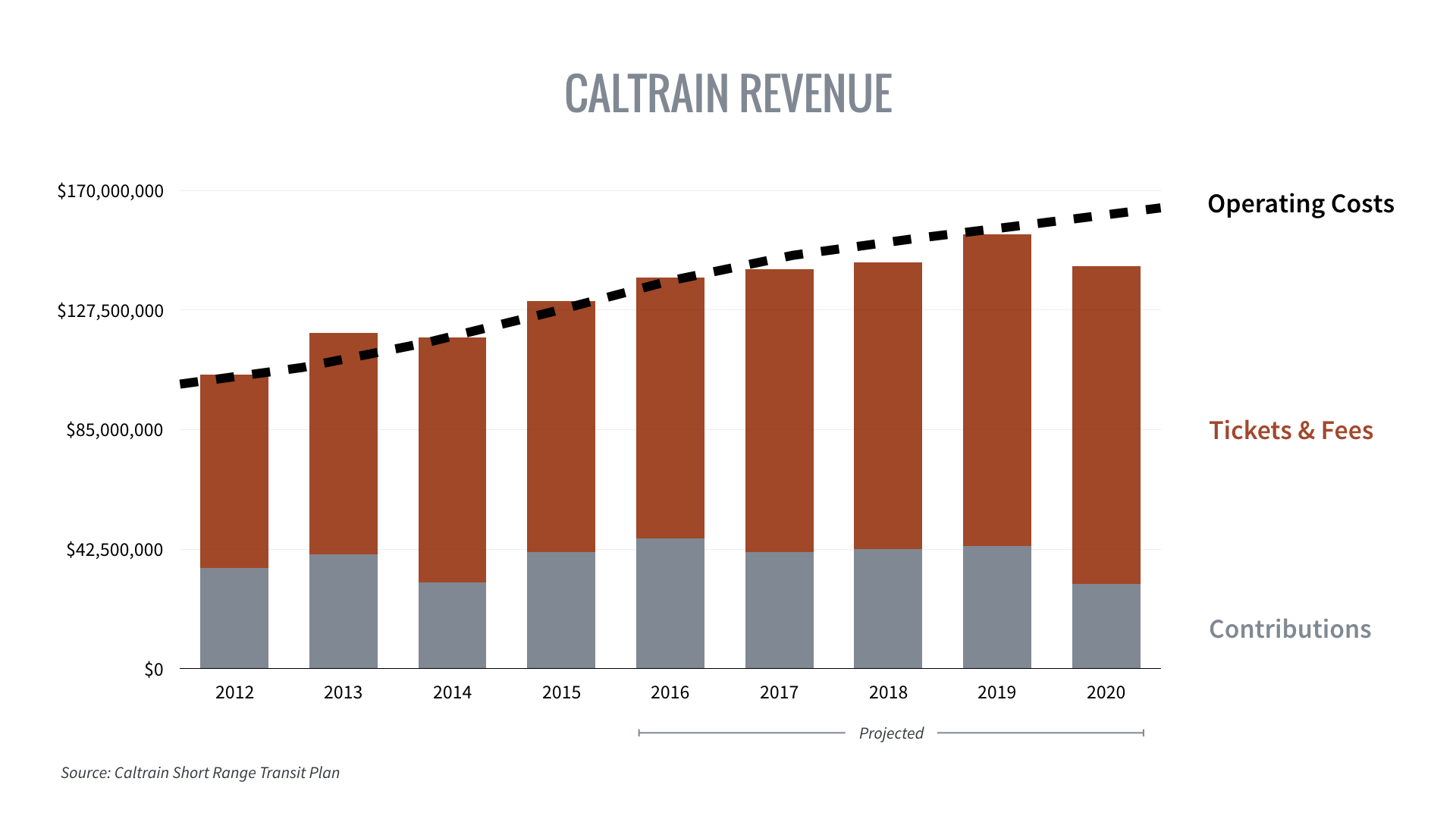

Due to historical legacies, however, Caltrain does not have a guaranteed source of tax revenue. Instead, it typically receives 30 to 35 percent of its operating budget through state and federal grants, and in voluntary contributions from the San Francisco, San Mateo and Santa Clara County transit agencies, who jointly oversee the Caltrain service. That leaves around 65 percent of the cost to be paid by riders through fares and other fees.

Yet relying so heavily on fare revenue makes Caltrain tickets more expensive than other Bay Area transit options, raising equity concerns that the service is unaffordable for working-class commuters. A weekday morning express train from San Jose to Palo Alto costs (before the proposed hike) $5.25 and takes 29 minutes. On the 522 bus run by the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority — which has dedicated funding — that trip costs $2, but it takes more than twice as long. So while the average Caltrain rider had a 2013 household income of $117,000, the typical VTA bus rider’s family made just $39,000.

This funding arrangement “sets up our system to be separate and unequal,” said Adina Levin, with the nonprofit Friends of Caltrain. “People would prefer to have a fast and relatively stress-free commute if it was cost-accessible for them.”

Levin said that high fares combine with other structural factors to push Caltrain beyond the reach of many workers. For example, she pointed to an informal survey of about 200 workers Friends of Caltrain helped conduct. While the survey has some limitations and so should be interpreted cautiously, it found that workers were much more likely to take public transit if they received a free or discounted pass from their employer, university or housing complex.

But Levin said these passes are offered primarily by tech firms and other large organizations to their well-paid staff, while lower-wage workers at restaurants, shops and service businesses have to pay the full ticket price — and so choose not to take the train.

The Epiphany, a small boutique hotel just two blocks from the Palo Alto train station, is one of the few exceptions to this trend. Around 80 percent of its 100 workers are low-income, and until recently, just ten regularly took the train. Then the hotel joined Caltrain’s Go Pass program, paying $180 per employee for annual unlimited-ride passes. Now between 30 and 40 percent of the staff take Caltrain, according to general manager Lorenz Maurer.

“It is actually now cheaper to take Caltrain than to drive,” Maurer said. The Epiphany asks workers who participate in the program to reimburse the hotel for their pass, but $15 a month is much less than the cost of gas and parking permits. Maurer added that for the hotel, offering transportation benefits “helps us retain employees and attract new employees as well.”

For Levin, the Epiphany’s example suggests one way to help lower-wage workers afford Caltrain. Right now, the Go Pass program costs employers a minimum of $15,120 a year, so it’s only cost effective for large companies with many workers. As a solution, Levin proposed that Caltrain allow businesses near a Caltrain station to pool together, so, for example, the various small restaurants and shops in downtown Palo Alto could collectively buy in and offer Go Passes to their cooks, waiters and store clerks.

“If we had a way to provide similar benefits to lower-income workers as to higher-income workers, we would end up with better equity, better environmental performance and better economic opportunity for people who need it,” she said.

Maurer noted, though, that there are also other obstacles that keep some of his workers from taking the train. Many kitchen staffers have shifts that end late at night, after the last train has passed. And poor integration between transit services makes taking Caltrain cumbersome and costly for workers who would need to transfer to light rail or a bus.

If those barriers were removed, Maurer predicted that more of his workers would sign up for Go Passes. “That would help us to swing the needle over 50 percent, I’m pretty sure,” he said.

There are projects underway that could help address some of those issues. Caltrain is preparing to move to electric trains, which would allow it to run more frequently and potentially later into the night. The regional Metropolitan Transportation Commission is considering spending $100 million to improve integration between transit services and is studying the possibility of creating a Bay Area-wide low-income fare program.

Still, those efforts won’t address Caltrain’s reliance on revenue from riders and the need for price increases. Caltrain officials say they’re seeking additional tax revenue, but since the system runs across county lines, they would either need to create a new taxing district similar to the one that supports BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit), run concurrent ballot measures in all three counties or obtain other smaller sources of funding. So for now, Caltrain projects that it will need additional fare hikes over the next several years.

“Finding a dedicated source of funding for Caltrain that can get us out of this situation where we depend on voluntary contributions and then our farebox is something that’s absolutely necessary,” Murphy said, but “we haven’t found a silver bullet.”

The Caltrain board will vote on the increases at its Dec. 3 meeting. If approved, fares would rise in February 2016, and parking fees would go up in July later that year.