In the 52nd minute of the San Jose Earthquakes’ match away to the Seattle Sounders on March 14, starting center defender Victor Bernardez received a red card and was sent from the field. To patch up the defense, Earthquakes’ second year midfielder JJ Koval, who makes $60,000 per year, moved to makeshift center back. His task? Stop Seattle forwards Clint Dempsey and Obafemi Martins. The two earn a combined $8.4 million per year.

With the help of Koval at center back, the Earthquakes secured its first win of the 2015 MLS season. The 3-2 road victory set the stage for the Earthquakes home opener on March 22, the inaugural MLS match in a new home stadium.

“Getting the win in Seattle in front of 39,000 fans was a great early season moment for the team,” Koval said on March 16. “It is always tough to get three points on the road … It’s funny to think that two weeks ago we were concerned we wouldn’t have a season.”

On March 2, negotiations over a new collective bargaining agreement between the MLS Player’s Union and league officials were at a standstill. The union wanted free agency, an increased salary cap and an increased minimum salary. The league did not want to give up ground. A player strike appeared imminent.

“I hoped an agreement would be reached,” Koval said. “Not only did I want to start playing games, but an increased minimum salary is a big deal for players in my situation.” But he wasn’t confident a deal would happen.

That day, Koval, one of five Earthquakes union representatives, was not in the D.C. negotiation room. Instead, fighting for a place in the starting lineup, he spent four hours at Earthquakes practice in the morning. After practice, he phoned in his opinion to other representatives. Then he had a quick burrito lunch and headed back out to his second job.

At 3 p.m. Koval was once again in his orange Adidas cleats. But instead of running around in the shadow of an 18,000-seat stadium, he was on a patchy Stanford intramural field, coaching a 10-year-old boy in an hour-long private lesson.

Koval, who was the ninth overall pick in the 2014 MLS Draft, and who became the 10th player in Earthquakes history to make 20 appearances in a rookie season, started doing private soccer lessons this past spring to bring in extra money. He typically does two sessions a week.

“Most people that come into the league are on a minimum contract. It makes it difficult to live in places like the Bay Area,” Koval said. “Which means that the guys who don’t make a lot of money can’t put all their focus on playing. We have to think about other ways to make money as well.”

Koval, who is getting married in 2016, also shares a room in a two-bedroom apartment in Palo Alto to keep his cost of living down.

“I am about to get married and want to be able to provide and make good money,” Koval said. “It would be nice to not have to live as frugally as possible. I would like to be able to marry my fiancée and choose a community we can enjoy without worrying too much about money.”

Last season, San Jose had nine players earn less than $50,000, according to the 2014 MLS player salaries released by the union. That includes Adam Jahn, a 24-year-old forward, who earned $48,500 last year, and who also found ways to earn a little extra on the side.

“The younger guys on the team like myself do a lot of extra appearances for the club to make money,” Jahn said.

Jahn, who has been on the paleo diet for over a year, has made several appearances at local elementary schools to talk about the importance of maintaining a healthy diet. This is part of the team’s “Get Earthquakes Fit” initiative that seeks to increase physical activity and health awareness for local students.

Not all MLS players are scrounging for extra money.

Some of the league’s top earners — Kaká, Clint Dempsey and Michael Bradley — make more money per year as individuals than the combined rosters of 12 MLS teams.

Team to team, the disparity is also immense.

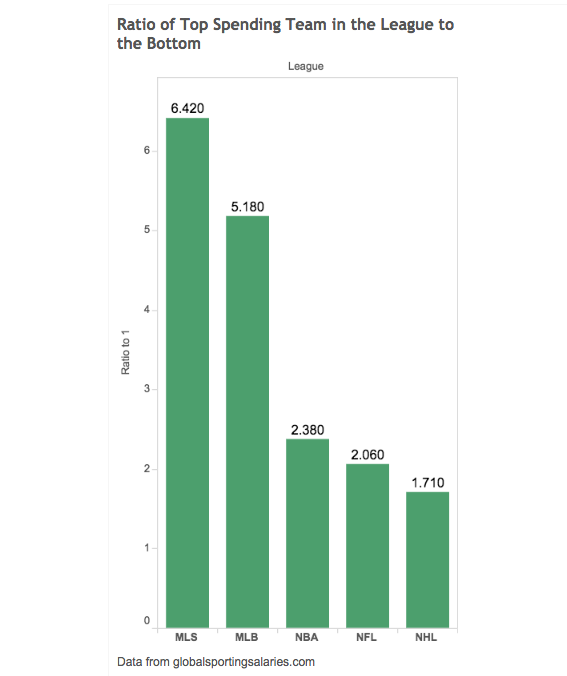

Comparing the five major American sports leagues, the ratio of the top spending team in the league to the bottom is highest in MLS.

This income disparity was one of many reasons that the MLS Player’s Union was on the brink of a strike.

“[Clint Dempsey] brings in a lot of money to the league,” Jahn said. “But for every Clint Dempsey there are 30 guys like me seeing the field, helping grow the league, and not getting justly compensated for it.”

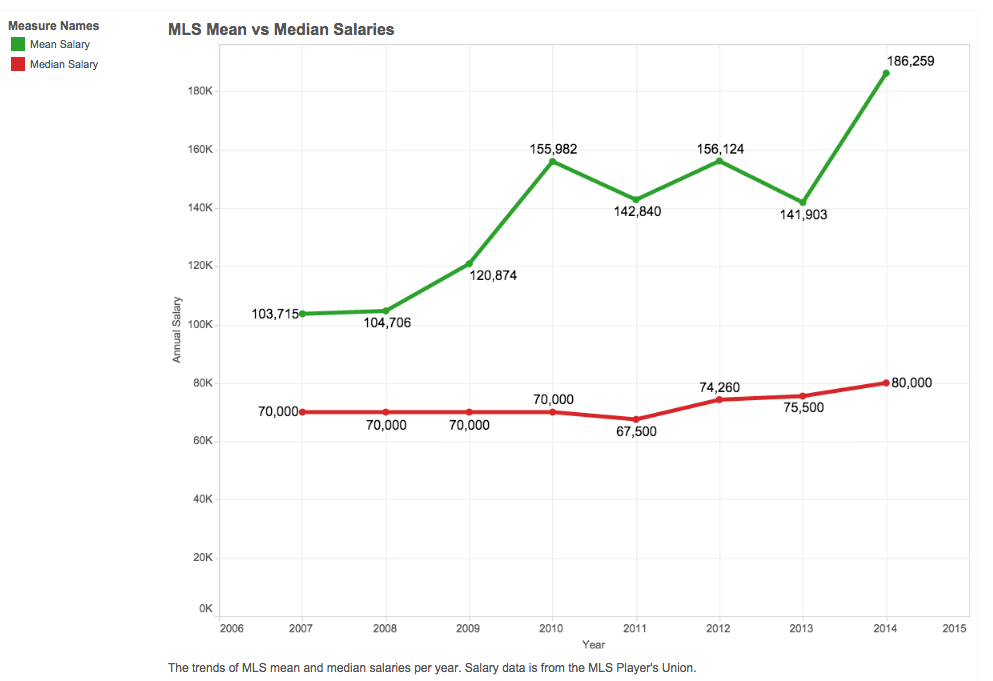

As the league has continued to grow, data shows that money has been allocated to players at the top of the earnings scale, instead of to the league’s majority.

Over the past seven years, the gap between the league’s mean and median annual salaries has increased dramatically. League money has been poured into designated players at the top of the earnings chart. The designated player system allows a maximum of three players per team to make over $387,500. This allowed the league to attract big names with contracts that lured talent away from bigger European leagues.

“The original point of the designated player was for big ticket draws,” said Bobby Warshaw, a former MLS player for FC Dallas, who now plays in Norway and writes about soccer as a freelance journalist. “From a soccer perspective, I think designated players are extraordinarily overvalued. There is not overwhelming evidence that they help you win.”

The designated player system is one reason the mean salary has increased by over $82,000 while the median has only increased by $10,000. The player’s union hoped that, with a new agreement, more revenue would be allocated to the league majority instead of just designated players. That way, players like Koval and Jahn could focus solely on being the best soccer player possible and not basic things like food.

“Healthy food is not cheap. I take home a double portion of lunch after training to eat later in the day because I don’t want to spend money on food,” Koval said. “As an athlete you should have optimal food for your body. Ideally, I shouldn’t have to worry about this. But if I don’t, all the little things add up.”

On March 4, Koval and Jahn both earned a $15,000 pay raise from their $45,000 salaries. An agreement was made two days before the MLS season opener. As part of the new deal, the league minimum salary was increased from $36,500 to $60,000.

The player’s union also managed to emerge with limited free agency, a seven-percent annual increase in salary cap for the next five years and reduced the time commitment for this agreement to five years. But critics say the deal could have been even sweeter.

“It’s not the deal they could have gotten based on the situation. It’s not good enough,” Warshaw said. “They had leverage to get more than they got. They didn’t get a major gain in anything.”

For example, it is estimated that only 10 percent of the league will meet the requirements for free agency, according to ESPN. Players have to be at least 28 and have played in the MLS for at least eight seasons. For young players, they can easily get stuck somewhere they do not want to be. That is a tough reality for a player who can be cut at any moment up until July 1 and not receive any compensation.

If there was any modest win, says Warshaw, it is the increase in minimum salary.

“An extra $15,000 does a lot for me,” Koval said March 16. “It gives me more room to find a place as I embark on this new stage in life with my future wife.” Koval and his fiancée have started scouting neighborhoods to live in near San Jose for 2016.

The new collective bargaining agreement reflects a league that is grappling to maintain financial control in the face of rapid expansion.

“The MLS has been very deliberate about their growth and expansion,” said Rick Burton, a professor of sports management at Syracuse University. “When the league first started, the league owned the teams. They dictated who went where.”

League officials used this control to make sure owners did not overpay for talent and stayed within the salary management system, Burton said.

But as the league grows, the structure is changing. Although the players did not get the free agency they hoped for, a limited version of it marks progress. And as salaries inch upwards, the league hopes to attract more talent.

“As the league gets better, you will have kids in America who think they can make big money in pro soccer,” Burton said. “Kids will think they can be a millionaire by playing soccer in the U.S. That will drive people to the league.”

The day when a majority of MLS players make millions — like they do in the top European leagues — is far away. And the gap in competition level remains daunting as well. That is why some are critical of the new MLS agreement.

“The more money put into the league, the more attractive it is for players,” Warshaw said. “It sounds like the negotiation was a monetary battle and not a how-can-the-soccer-be-better battle. It’s a difference of philosophy.”