It was as simple as walking down the hall.

Before COVID-19 shut down school campuses, if a San Mateo County student felt anxiety welling up in her chest, she could slip out of class and find the school counselor’s office just down the hallway. If a student was hurt by a friend’s put-down at lunch, he could show up unannounced, knowing a mental health professional was on the other side of the door willing to talk it out.

With the shift to online instruction, students are saying that they took for granted their ability to get on-campus, immediate counseling support. “Now you have to make an appointment, and they might be unavailable for weeks,” said Milagros Benitez-Cibrian, a sophomore at Aragon High School in San Mateo.

Many schools are struggling to respond to heightened levels of student anxiety seven months into the pandemic. In one national study, 60% of students said they find it harder to get support.

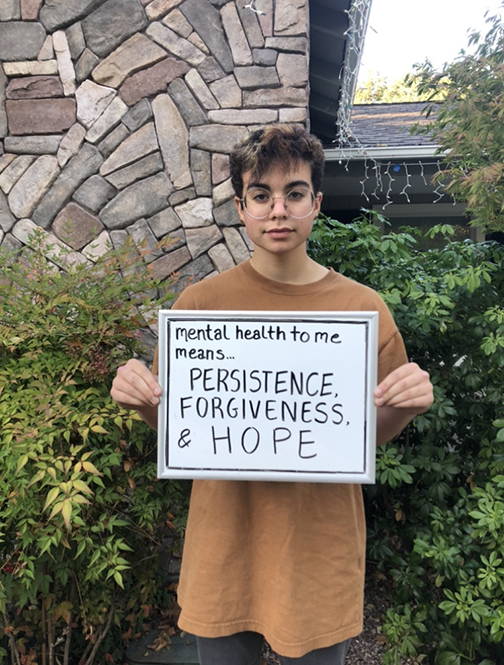

“Virtual school has presented barriers to getting help, for myself and other students,” said Novak Chernesky, a senior at Crystal Springs Uplands School. “There’s the problem of not having reliable internet access and not having the privacy or space to talk to a therapist.”

At his private school in Hillsborough, Chernesky leads a student group dedicated to spreading awareness about mental health and well-being. He agreed that the experience of being able to walk to the counselor’s office can’t be re-created online. “Now there’s this added degree of separation, and it’s much easier for students to talk themselves out of reaching out,” Chernesky said.

The pandemic has contributed to an increase in loneliness and anxiety, according to a recent Kaiser Family Foundation study. About 45% of the teenagers surveyed indicated they felt more stress than usual.

At San Mateo High School, Counseling Department Chair Andrea Booth noted that “there was already a pretty high level of stress among our students and the pandemic has only amplified mental health issues.”

“I’m seeing academic pressure, anxiety, depression, and family conflict, and all of that is exacerbated because we’re far away and there’s no in-person connection,” Booth said. “It’s put an unprecedented burden on our students, families, and our faculty.”

April Torres, mental health manager for the San Mateo Union High School District, sees students and families reaching out more than ever. At the same time, she said, there has been an increase in reports to the county’s Child Protective Services and Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children agencies. Torres attributed this to a “unique combination of the public health crisis, social isolation, and the economic recession.”

In addition to the challenges of virtual care, schools must determine what providing care entails in the face of budget cuts. Although San Mateo County has one of the highest median household incomes in the San Francisco Bay Area, it is not immune to financial pressures.

“We are facing long-term budget effects from this pandemic,” Torres said. “Grants and other means of support for mental health services are on the forefront [of cutbacks].”

Some school departments lack the resources they need. At most of the public high schools in the county, there are four or five counselors for a couple thousand students. At the private Crystal Springs Uplands, one counselor manages the care of over 400 students. “She not only is a counselor but also teaches part of wellness programming to various grades,” Chernesky said.

“We do have a diverse student body but our mental health resources cater to a specific type of students,” he said. “We’ve never really had conversations around culturally conscious mental health resources in response to incidents of racism or homophobia that occur.” The national conversation over racial justice has led some students to seek support around identity and inclusion, Chernesky added.

With limited personnel and great demand for services, under-resourced and under-represented students are affected the most. While some students in the county access mental health care through outside providers, low-income students are more likely than their counterparts to be uninsured and unable to afford therapy and other services.

“School closures can be especially disruptive for children from lower-socioeconomic families, who are disproportionately likely to receive mental health services exclusively from schools,” Torres said.

Benitez-Cibrian said it’s been much harder for her to access support during the pandemic due to the more structured nature of online services and lack of privacy at home. “Even if you get an appointment, you’re at home with your parents and don’t want them to be aware of your mental health,” she said.

Despite relying so strongly on the school system, many low-income students and their families don’t have access to online resources or the tech support to get teletherapy, Booth said, adding, “There are families who don’t know how to navigate the system online, and there are families who are moving around or who are homeless, so getting regular help is not feasible.”

She said San Mateo High School and other schools in the district simply do not have the resources to account for these barriers.

The burden of responding often falls on teachers.

Sophia Olson, a senior at Crystal Springs Uplands School, said that her teachers play an integral role in supporting her.

“I’m grateful to some of my teachers who were there for me throughout high school and especially during the pandemic,” she said, “but they definitely took that burden of what I was experiencing and how I was dealing with my emotions.” She said many students at Crystal rely on their teachers because the lone school counselor has a multitude of responsibilities for so many students.

Natalie Hilderbrand, a student at the private Menlo School, echoed Olson. “I think that’s a lot to ask of these teachers who aren’t mental health professionals, and ideally doing everything through more counselors would be better,” Hilderbrand said.

Torres said her school district trains staff to be aware of common causes of mental health challenges and to recognize signs of distress, but does not “expect teachers to replace trained mental health professionals.”

Booth said, however, that teachers really are on the frontlines because they’re seeing students everyday.

“This is a work in progres,” Booth said. “We have to be more innovative in supporting our students, and that innovation can definitely be exhausting. It takes a village, and right now it will take a virtual village.”