One Pennsylvania county official claims his voting machines are unhackable. Another admits hers are old, but the county can’t afford to buy new ones. A third says he’s waiting for the state to tell him which new voting machines are safest for Pennsylvania voters.

At a time of national concern over foreign interference in U.S. elections, 57 percent of the voters in Pennsylvania, including Philadelphia’s, are casting their ballots on machines that are outdated, hackable, and don’t provide a paper record of each vote to safeguard against fraud.

After Texas, Pennsylvania has the most registered voters using machines with no paper trail, according to Verified Voting, a nonpartisan group promoting trustworthy voting systems.

In February, Gov. Wolf and Secretary of State Robert Torres told counties that any voting machines they buy must be able to produce a paper record for each individual vote. The state didn’t include any funding to help counties purchase new equipment and hasn’t yet certified any models.

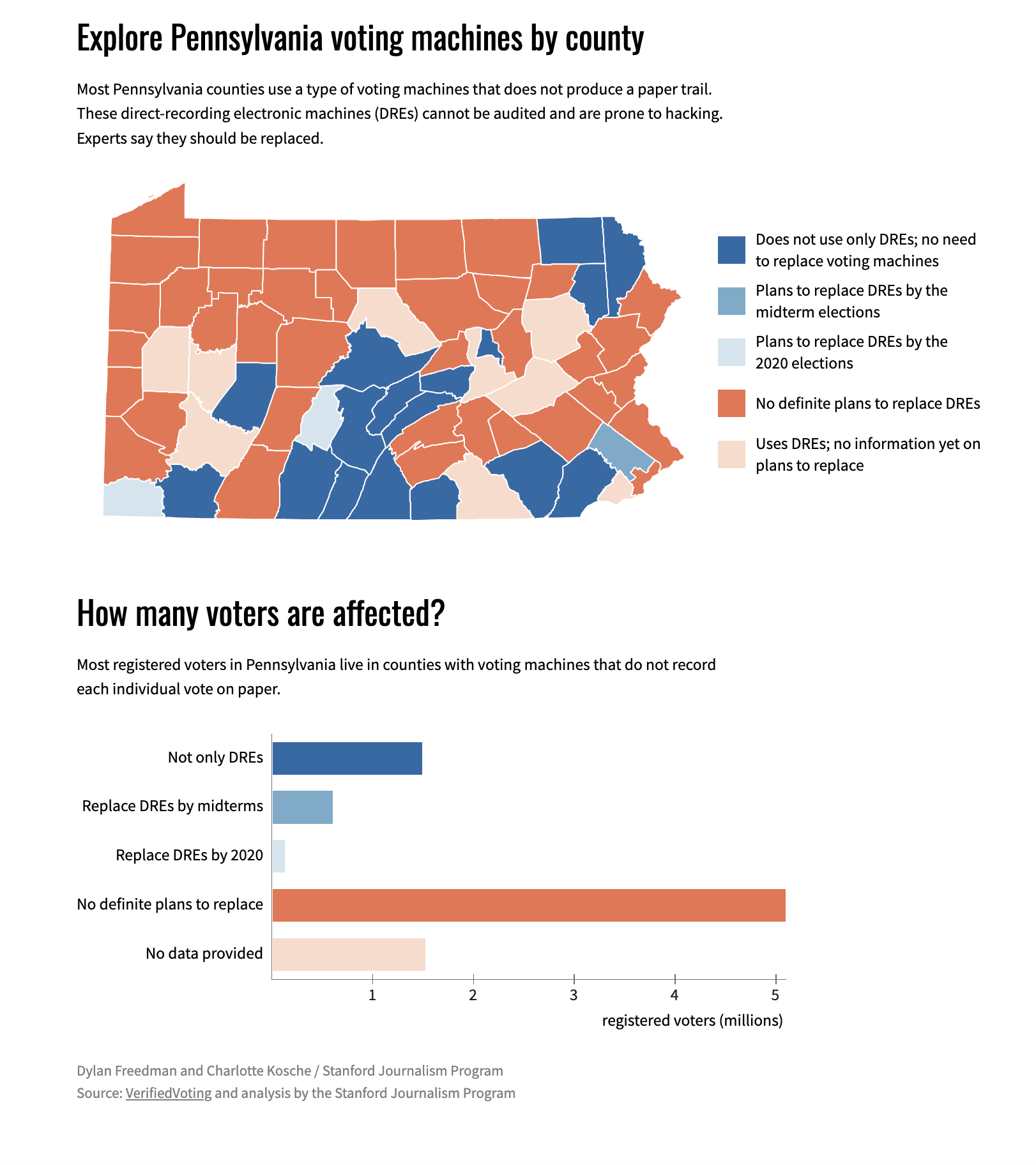

Most of Pennsylvania’s counties — 50 out of 67 — use machines with no paper trail. (New Jersey, Delaware, and three Southern states rely entirely on the problematic machines.)

Earlier this year, reporters from the graduate journalism program at Stanford University contacted those 50 counties about their plans to upgrade their voting equipment. Of the 41 that responded, only Montgomery County intends to replace its machines in time for the 2018 midterm election. Officials from just three counties — Beaver, Blair, and Greene — said they expect to have appropriate machines by the 2020 presidential election.

Officials in the other counties gave a host of reasons for keeping the vulnerable systems:

- The new technology could cost millions of dollars at a time of stretched budgets.

- The state’s directive was an unfunded mandate they didn’t have to follow.

- The current machines aren’t at peril because they’re not connected to the internet.

- No recounts had been challenged, so why change?

During the 2016 presidential election, Pennsylvania had failures in at least 30 machines in Lebanon, Cumberland, Perry, and Butler Counties.

Dauphin County, which includes Harrisburg, relies on machines installed in 1985, about two decades past the manufacturer’s suggested replacement date. Jerry Feaser, county director of elections and voter registration, said of his vintage machines:

“I could put the machine in the Red Square in Moscow and I would bet that no Russian would be able to hack it unless they came at it with an ax.” Plus, he said, it could cost $5 million for new ones.

His comfort isn’t shared by Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielsen, who warned the Senate Intelligence Committee in late March:

“We recognize that the 2018 midterm and future elections are clearly potential targets for Russian hacking attempts.” She endorsed paper ballots. “If there’s no way to audit the election, that’s absolutely a national security issue.”

In late March, Congress approved spending $380 million to boost the security of election systems across the country, with Pennsylvania projected to get $13.5 million.

But it’s not enough to cover the costs of replacing the machines, said Marian Schneider, former adviser to Wolf on election policy and deputy secretary at the Pennsylvania Department of State. As president of Verified Voting, she urges all states to switch to safer machines by 2020.

She added that Pennsylvania could do three things that would speed replacement of problematic machines: Allocate state funding; decertify the vulnerable machines, which would force counties to replace equipment; and identify acceptable replacement machines.

The secretary of state will announce a handful of certified models in the coming weeks and months, said agency spokeswoman Wanda Murren.

If the state really wants to be ambitious, it could make the changeover by the 2018 midterms, Schneider said.

“I’m not saying it’s going to be easy,” Schneider said. “But I think we should try.”

Surprising turnout

On a rainy Saturday morning in February, officials in Montgomery County invited voters to give feedback about new voting equipment the county was considering buying — all of it featured some form of paper audit for each vote cast. The county expected 100 or fewer attendees, but 300 citizens showed up, including Ayodele Fitzgerald, a resident of Abington.

“As elections become more and more contentious we need bipartisan oversight but also the ability to investigate if necessary,” Fitzgerald said. A paper backup “gives a sense of security that may help people feel their vote, their voice, is being heard.”

Using paper ballots isn’t as low-tech as it might sound. With optical scan systems, voters fill in bubbles indicating their choices and then the ballot is scanned and tabulated electronically. Officials retain the paper ballots in case they are needed.

In a swing state like Pennsylvania, where the last presidential election was decided by fewer than 50,000 votes, safeguarding Montgomery County’s 577,000 voters can make a difference. Officials said they don’t yet know how much the new machines will cost.

At least 13 counties have come up with estimates for the eventual cost of new voting machines: Cameron County, with slightly more than 3,200 registered voters, estimated the tab to be at least $100,000; Dauphin and Berks Counties, with more than 450,000 voters combined, said new systems would cost $3 million to $5 million.

Of those three, Cameron County is waiting for state certification of machines it can install. Dauphin and Berks have no plans to replace their machines. Philadelphia and Allegheny Counties say they are looking at replacing voting equipment but have no timeline or estimates. Northampton County would have to “come up with several million dollars” to replace its paperless voting machines, said David Zawick, the custodian for the county’s voting machines, which were purchased in 2008.

“There’s always complaints every year as far as the paper trail,” Zawick said. The county doesn’t intend to replace all of its old machines until mandated to do so.

Replacing all 700 of Lehigh County’s machines would take $3.5 million, said Timothy Benyo, the chief clerk of voter registration and elections. He suggested that most counties would have to raise local taxes to cover the cost.

“There’s not a surplus of money anywhere to fund the machines,” Benyo said.

Securing funding to help counties replace machines is a priority this year for the County Commissioners Association of Pennsylvania, a lobbying group that represents Pennsylvania counties, said executive director Douglas Hill.

“Almost all of our counties are ready to move forward, \[but\] some of them have it as a higher priority,” Hill said. “I think that for many of them it really is a matter of affordability.”

Hacked in minutes

In 2007, Princeton University computer-science professor Andrew Appel obtained access to a 1996 Sequoia AVC Advantage, a type of voting machine in use today in Montgomery and Northampton Counties. He wanted to see if he could hack it.

It took him only minutes. With no paper record, the AVC Advantage and others like it have little chance to show failures, deliberate or otherwise. The AVC Advantage is a “direct-recording electronic” voting machine, or DRE. Widely used, DREs feature push-buttons, touchscreens, or dials to record a voter’s vote directly into computer memory.

In 2006, many Pennsylvania counties installed scores of the DRE machines using federal funding from the Help America Vote Act (HAVA). The law was enacted after the 2000 presidential recount in which incompletely punched holes in paper ballots — “hanging chads” — caused confusion in Florida over which candidate was selected by the voter and forced the disqualification of thousands of votes.

In Dauphin County, its DRE machines “predated the internet,” election official Feaser said. “The only outlet is the electrical switch. The machines are self-contained computers.”

Feaser said the county tests each machine before use and audits each machine by printing a randomly generated representation of each individual vote cast.

‘A lot of flaws’

Even so, DRE machines are computer systems, at risk to system crashes or hacking, the Brennan Center for Justice reported in March.

Computers used to program election machines may have previously been connected to a network and can pose a risk, said Daniel Lopresti, a computer science professor at Lehigh University.

“Even if it isn’t connected to the internet now, it might have been connected to the internet two years ago,” Lopresti said. “And even if it was never connected to the internet, it’s still running software that has a lot flaws in it because it’s running a standard operating system.”

From 2006 through 2008, Lopresti and several students acquired four types of DRE machines, took one apart and analyzed all of the machines’ electronic circuitry to see how they could be manipulated. The answer: easily.

“That would just probably take about 15 minutes to take the back off the machine and insert new firmware chips and close it back up again,” Lopresti said.

Lessons from New Mexico

Pennsylvania could look to New Mexico as an example for how to replace its voting machines. The state’s 33 counties all use a combination of optical scan paper ballot systems and ballot marking devices at their polling places. Both systems count votes electronically, but they leave a paper trail that is stored for 22 months to verify the accuracy of the results.

New Mexico election officials had issues with DRE machines back in 2004, when the machines’ inability to produce an audit trail complicated recount efforts in swing precincts, said Joey Keefe, communications director for the

New Mexico Secretary of State. The New Mexico Legislature passed a plan requiring the use of paper ballots in its election systems in 2006. Keefe said that the state replaced its machines again in 2014 again due to aging memory cards and machines, but he is “confident that our current system is very secure.”

New Mexico was one of 11 states to receive a B grade from the Center for American Progress in a recent survey of election security, largely owing to that use of paper ballots and its ballot accounting and reconciliation procedures. No states received an A, Pennsylvania received a D and five states received an F.

A ‘no-brainer’

There are also lessons to be learned from the 13 Pennsylvania counties already using voting machines with a paper trail.

Montour County, for instance, switched in 2006 from using punch-card ballots to optical scan machines.

Director of Elections Holly Brandon said it cost the county of about 20,000 residents less than $200,000 to make the switch to optical scanners. It was an easy decision, she said.

“It kind of seemed like a no-brainer to us,” Brandon said. “We were concerned about integrity in the process. And with the optical scan, I can actually hold the entire election in my hand — because we’re using paper.”

This story was written by Katlyn Alo and Jackie Botts and reported by Alo, Botts, Amy Cruz, Christina Egerstrom, Marnette Federis, Dylan Freedman, Charlotte Kosche, Noemie Levy, Michael McLaughlin, Anthony Miller, Jacob Nierenberg, Marta Oliver-Craviotto, Isha Salian, and Simone Stolzoff.