While hiking at 8 a.m. on March 7 in Portola Valley, a bucolic town nestled in the hills behind Stanford University, Ted Driscoll suddenly came face-to-face with an adult mountain lion. The large feline bounded within 10 feet of him and stared, growled and roared.

Driscoll, who stands 6 feet 3 inches tall, extended his hands above his head to make himself look bigger. He began to shout and stared directly into its eyes. After a tense standoff, the cat finally turned around and sauntered off.

A five-term former mayor of Portola Valley, 65-year-old Driscoll is an avid runner. He hits 45 miles a week and runs marathons for fun. On the few days he doesn’t run, he walks “five or 10 miles.”

These days, he says he’s sharing his terrain more with the big cats.

“I’ve seen mountain lions at least a half dozen times in the last couple years. They often are 50 or 100 feet ahead of me on the trail. I come around a corner, and there they are,” Driscoll says. “And they always take off. They always run away. They do not like humans. It’s obvious.”

Mountain lions — also known as pumas or cougars, depending on your vernacular — grow to be six to eight feet long. They have a sturdy, muscular frame and a long tail that curves to the ground and often has a blackish tip. The predator is at the top of the food chain in the Bay Area, where it commonly hunts deer and other small prey like raccoons and foxes.

Over the past 30 years, mountain lions have become more frequently sighted in the Santa Cruz mountain range, which peaks above the infamous San Andreas fault line tearing through Silicon Valley. Wildlife experts hypothesize that irrigated lawns attract deer and that, in turn, has brought the mountain lions in increasing numbers over the past decade to urban sprawls. No authoritative scientific study has conclusively demonstrated that the population is increasing, or what other factors could be causing increased sightings in the Bay Area.

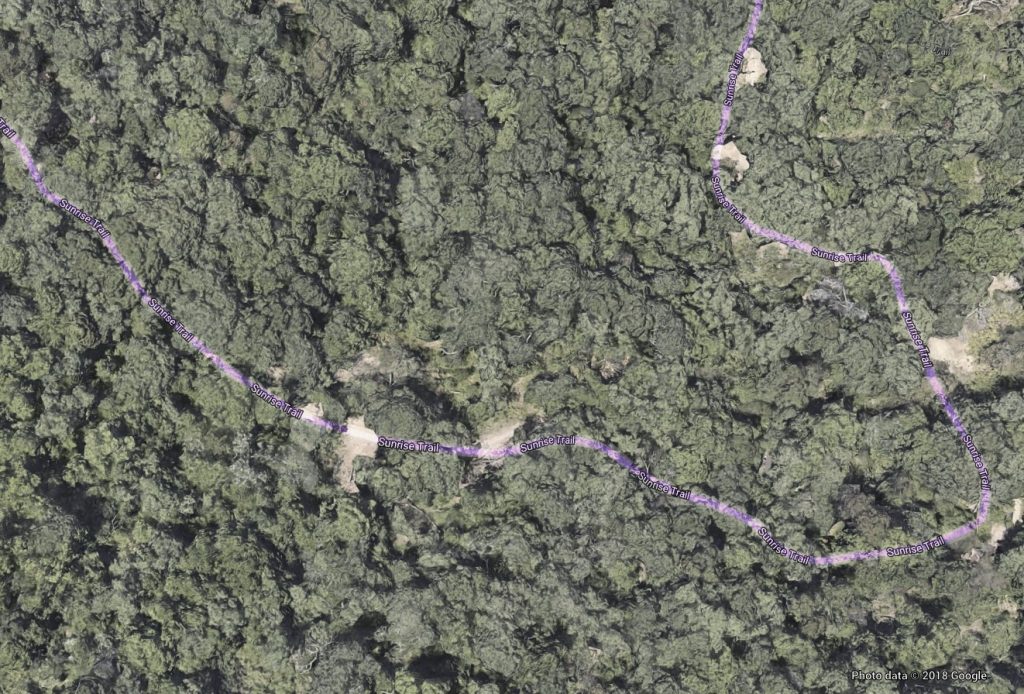

Portola Valley’s winding trail system cycles through lush overgrowth, mysterious ponds and expansive fields. “Peripatetic in Portola Valley,” an essay written by a long-time resident, captures the allure of the casual jog: “To get around and see everything it helps to be able to run intrepidly along trails, through the brush and up and down hills.” The piece is featured on the “About” page of Portola Valley’s website.

Driscoll’s “unprecedented 20 years of service” to the unincorporated town government was the subject of a recent tribute piece in The Almanac, a news publication that covers the area. But what’s less well-known to the community was his cool-headedness in close encounters with powerful felines in the community’s woodlands.

“I was just walking along, and all of a sudden I heard something behind me, and I turned around. And this thing was running up to me and it was making growling noises at me, so it was obviously upset,” Driscoll recalls.

“I put my hands up. I shouted at the thing. It growled at me very loudly, and it stopped about 10 feet behind me on the trail while I was facing toward it. And it kind of stared at me for five seconds. And I stared at it and shouted and it growled.” Driscoll pauses. “And then it just turned around and walked away.

“All I can say is, I was keeping an eye on my back the rest of the walk,” he admits.

The mountain lion, in Driscoll’s estimation, was between 150 and 180 pounds and had an extraordinarily long tail. Driscoll is unsure why the creature approached him so aggressively, but he speculates it was looking out for its cub.

Portola Valley closed Sunrise Trail, where Driscoll’s encounter occurred, on March 8.

“This aggressive mountain lion encounter was out of the ordinary for Portola Valley,” spokesperson for the town said. “That is why out of an abundance of caution the Town took the extraordinary step to close the Sunrise Trail for a week.” A news posting on the town’s website on March 8 speculated that the mountain lion may have been “protecting her young cub.”

San Mateo County issued a wildlife alert in response to the incident as well, also using the word “aggressive” to portray the mountain lion. Driscoll seemed less fazed by the incident.

“I personally think that the SMC alert and closing the trail is a bit excessive, because there are so many trails in town, and the mountain lions are crossing these trails all the time,” Driscoll said.

The issue prompted the town to contact the San Mateo County Sheriff’s Office for assistance in determining if a potentially aggressive mountain lion was still present in the area. A sheriff deputy contacted a warden from the California Department of Fish & Wildlife, and they combed the one-mile trail together looking for any signs of mountain lion activity.

The cat left no sign of its presence. Absent conclusive evidence it remained in the region, and because mountain lions are by nature roaming creatures, Portola Valley reopened the trail one week later on March 15.

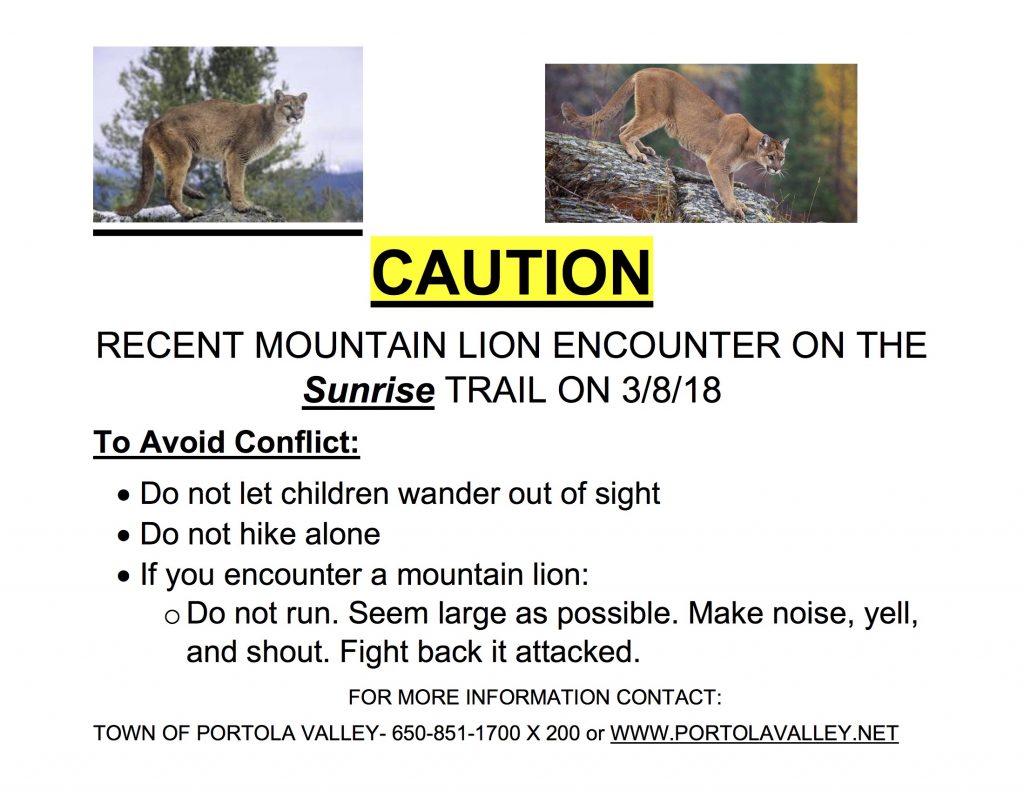

The reopening of the Sunrise trail was accompanied with a caution sign outlining what to do in a mountain lion encounter. A news release on the reopening of the trail on Portola Valley’s website outlines the steps:

- Always be aware of your surroundings.

- Do not hike, bike, or jog alone.

- Avoid hiking or jogging when mountain lions are most active during dawn, dusk, and at night.

- Keep a close watch on small children and pets when on the trails.

- Don’t feed deer; it is illegal in California and it will attract mountain lions.

- Do not approach a mountain lion.

- If you encounter a mountain lion, do not run; instead, face the animal, make noise and try to look bigger by waving your arms; throw rocks or other objects. Pick up small children.

- If attacked, fight back.

In a rapidly urbanizing area coming to grips with the wildlife it displaces, Driscoll’s experience provides a real-life lesson in how to survive an encounter with a mountain lion. Though Driscoll admits he was scared, he remained in control of the situation and avoided harm.

“It was definitely a surprise, a major shock. I was stunned. I never expected to see this,” Driscoll recalls. “I think it was just a unique experience. It was just a little surprising to suddenly be shouting at a mountain lion, and the mountain lion growling at me 10 feet away.”