The deadly wildfires that ravaged the Sonoma region in October prompted local officials to reevaluate how they issue warnings in times of extreme emergency. But the fires also highlighted another communication problem that officials hope other communities will learn from before the next disaster: inadequate disaster information in Spanish to reach the large Latino population.

Sonoma County leaders are also pointing to fear of immigration enforcement as a key barrier that prevented immigrant communities from seeking aid following the most destructive fires in California’s history.

And as California natural disasters become potentially more damaging in an era of climate change and rapid urbanization, lessons learned during the wine country fires could help other jurisdictions bridge potentially fatal communication barriers during future emergencies, local officials and advocates said.

“I think Sonoma County’s in a great place to understand that language access is the difference between life and death in these kinds of situations,” said Alegría De La Cruz, the county’s Chief Deputy Counsel.

The wildfires, which broke out in the late evening hours of Oct. 8, ravaged over 200,000 acres of land and over 8,000 structures in Northern California, including vineyards, hospitals, hotels, schools and homes in the Sonoma region, famed for its wine industry. In the wake of increasing immigration enforcement under President Donald Trump, many undocumented evacuees camped on beaches and slept in cars rather than in shelters where they feared government agents would round them up.

The county scrambled to publish alerts and information in Spanish. After the fires, the California Department of Health and Human Services published a guide to disaster assistance services for immigrant Californians in both Spanish and English following requests for that information from Sonoma County.

“If no information is provided, that gives the opportunity for misinformation,” said Bernice Espinoza, a deputy public defender and criminal immigration specialist, referring to the spread of rumors that immigration agents were present at shelters and relief centers.

A growing immigrant population

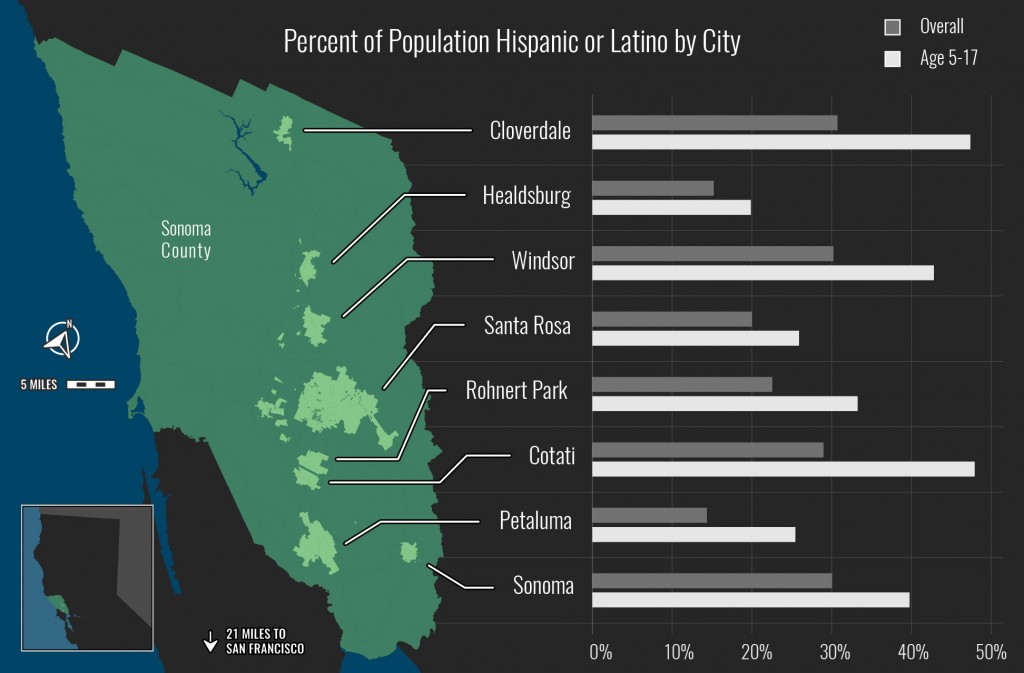

While about a quarter of Sonoma County’s population is Hispanic or Latino, among the county’s youth the proportion is 43.9 percent, according to 2016 data from the US Census which indicates a growing second generation of Latino immigrants. The Latino population grew by more than 60 percent between 2000 and 2015, Reuters reported.

Estimates on the number of undocumented living in Sonoma County vary widely, from 28,000 to 38,500. A 2014 Migration Policy Institute report estimated that 4,000 were eligible for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, a program canceled by President Trump two months ago, which shielded people who had arrived in the country as youth from deportation.

According to Espinoza, the county didn’t anticipate that many people with legal status would fear contacting officials because of undocumented family members they wished to protect.

This lack of “familiarity with who lives in the affected communities” left the county unprepared to communicate information in other languages or attend to the fears of immigrant populations, said Espinoza, who informally stepped into the role of language coordinator when she realized no such position existed in the county’s emergency response plan. She spoke to Spanish-language media, translated documents and interpreted press conferences, while coordinating bilingual staff and volunteers at the county’s emergency-activated Local Assistance Center (LAC). She added that sizable Eritrean, Fijian, Cambodian and Laotian communities might not have received critical information in their native languages.

The county is also home to immigrants from the South of Mexico who speak indigenous languages such as Mixteco, Triqui and Chatino. “I feel that when providers talk about [the] Latino community, they feel that they already covered everyone,” said Mariano Alvarez, an indigenous community worker at a rural-focused legal nonprofit, emphasizing that many indigenous Mexicans can’t speak English or Spanish.

Espinoza and other officials say the county needs to gather more detailed demographic information and to include more bilingual staff in their emergency plan.

But this may be difficult, according to Ronit Rubinoff, director of a Sonoma legal aid nonprofit. “We know there’s always a certain number of people in this county that are invisible,” she said.

“We have already driven underground those folks with the hostile immigration rhetoric,” Rubinoff added, describing undocumented individuals who were “un-enrolling from public benefits from the county” out of fear of having their names recorded, even before the fires.

Fear, rumors and information delays

During the first week of the fire, county officials struggled to organize timely evacuation alerts and disaster information in Spanish. Several Spanish-language radio stations filled the gap. KBBF, a bilingual community radio station, stepped up to provide round-the-clock coverage of the fires in Spanish. But, this was out of necessity, according to one of the show’s contributors, Rafael Vazquez, who said that “the county wasn’t prepared to translate anything.”

However, soon the county translated California Fire Incident Reports twice daily and hosted a Spanish-language fire incident press conference, both firsts in CalFire history, according to county affairs analyst Hannah Euser.

The county’s LAC, where dozens of government agencies and nonprofits set up disaster relief booths, also saw a conspicuous lack of Latino aid-seekers, according to De La Cruz.

“From the start, I think the LAC was set up for the citizen population and not [the undocumented],” said Rubinoff, pointing to a lack of interpretation services.

But even with timely and sensitive communication in Spanish, convincing undocumented immigrants that local government is there to protect them is an uphill battle, according to County Supervisor Lynda Hopkins.

“There’s so much fear in the undocumented community right now that they don’t even trust local government to provide for their needs in the evacuation shelters,” Hopkins said.

Exacerbated fears

Ten days into the fire, an ICE press release incorrectly implied that an undocumented immigrant may have kindled the deadly fires and called the county an “uncooperative jurisdiction,” prompting the Sonoma County Sheriff to publicly denounce the statement as “inaccurate” and “inflammatory.”

Then, as impacted residents began applying for aid from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, people took notice of a clause on registration forms which states that personal information “may be subject to sharing” with ICE. While undocumented adults are not eligible themselves, they can apply on behalf of members of the household who are documented minors.

But De La Cruz, the chief deputy county counsel, believes many have chosen not to apply, fearing they may expose themselves to immigration agents in the process, despite promises from the county that it would do its best to defend such cases.

Grassroots efforts step up

From the moment the fires broke out, Sonoma County residents mobilized to provide informal alerts, aid and shelter for residents who feared government-run emergency programs.

At Windsor High School, hundreds of large boxes of donated food, clothes and toys were dropped off at a grassroots evacuation shelter run by mostly Latino college students. “The evac center’s built from just community members,” said volunteer Omar Santiago, 22, alongside other volunteers as young as ten.

“We’ve been taking clothing, especially warm clothes, tents, sleeping bags, and everything else to several locations by the beach,” added Vazquez, who helped coordinate the effort. National Guard officials stationed at shelters in the interest of public safety deterred many without legal status, he said.

During the second week of the fire, three local nonprofits launched UndocuFund, a crowdfunded effort to provide ongoing aid to undocumented individuals who are ineligible or too scared to apply for FEMA. As of November 13, UndocuFund had raised about $1.8 million of its $5 million goal and over a thousand families had begun to apply for aid.

On Saturday, Oct. 21, a coalition of nonprofits, organizers, and county officials assembled the county’s first ever Spanish-language town hall to discuss the path forward for the Latino community. About 150 people attended the event that brought together affected families, police, fire chiefs, county officials, Santa Rosa’s mayor, and state senators and congressmen — but several thousand watched the live video on Facebook.

“This is the moment for us to begin to think about how we are going to rebuild with the Latino community in mind,” said Ana Lugo, president of the grassroots nonprofit North Bay Organizing Project, at the event’s start.

While Supervisor Hopkins saw the town hall as a stepping stone, she wished it had been better attended. “People are nervous to be inside a building because they’re worried that it’s going to be a trap from ICE,” she added.

Rising from the ashes

While the disaster laid bare the fears of undocumented residents, it also revealed opportunities for better emergency preparedness that keeps even the most vulnerable residents in mind. Some local leaders see the fires as a critical opportunity to establish better dialogue and trust between local government and the immigrant community.

One such initiative is “Sonoma County Rises / Sonoma County Se Levanta,” a collective of nonprofit and elected officials that has created a website to solicit feedback from those affected by the fires to rebuild a more resilient, equitable community.

Hopkins, who’s on the collective’s board, envisions a series of town halls in local communities, because “all of those decisions being made and all of those initiatives should ultimately be guided by community voice and community representation.”

Before the fires, Sonoma County “already had tremendous income disparities, tremendous educational attainment disparities, a huge lack of affordable housing and a lot of people who felt silent because they were undocumented,” Hopkins said, but she’s optimistic. The “silver positive lining,” according to Rubinoff, is that fires have helped push local leaders to action.

De La Cruz and Espinoza hope for more Spanish speakers at future press conferences and town halls. “To see somebody in uniform speaking in Spanish and addressing your concerns as an undocumented person in the community” is very meaningful, De La Cruz said.