On Nov. 9, 2016, the day after the presidential election, 15 Bay Area artists-cum-activists sat down in a kitchen in San Francisco. Some of the younger ones, students at the San Francisco Arts Institute, struggled to find words to encompass their outrage and confusion over the election of Donald Trump. But the more seasoned artists focused on action. Their goal: ten poster designs by the next day.

“This is how revolution starts,” one of the art students said.

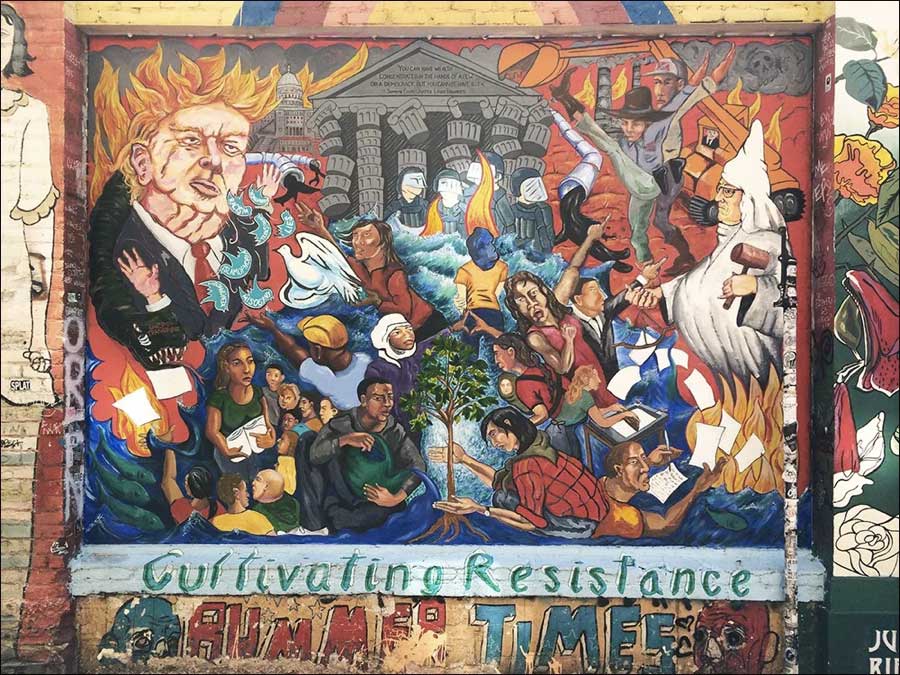

This kitchen gathering was a meeting of the SF Poster Syndicate, which creates and distributes screen-printed political art live in the streets of San Francisco, and the designs they drafted in an act of protest that post-election night have evolved into a full-scale mural. Since December, Clarion Alley in San Francisco’s Mission District has featured an image of President Trump, mouth spewing Twitter-logo birds, accompanied by other bogeymen in the background, all bearing into a huddle of community activists who shelter a sapling with their bodies.

In this moment, “people are really hungry for political art,” said Christopher Statton, a co-director of the Clarion Alley Mural Project (CAMP), which oversees the alley. But political commentary is nothing new for the 560-foot-long walkway, which houses over a hundred murals, large and small, alongside the Trump piece. For more than 20 years, through changing times and gentrification, the Clarion Alley Mural Project has provided wall space for social and political commentary via paint.

Clarion Alley encapsulates San Francisco’s Mission District, a neighborhood that is culturally rich but also rife with tension. Situated between 17th and 18th Streets, it bridges the neighborhood’s two arteries, Mission and Valencia. On the corner of Clarion and Mission, you can buy cream, plastic-looking heels for $6.99 from Footwear City Express/Ciudad de Zapatos. It houses what FiveThirtyEight deemed the nation’s best burrito, and when I visited, it was noisy with the sounds of passing buses and hip-hop blaring from a speaker someone lugged down the sidewalk. Valencia, meanwhile, has a high per-capita number of tungsten bulbs and juice shops.

But both streets, and the entire Mission District, have undergone drastic changes in the last 30 years. According to a report by Berkeley researchers Miriam Zuk and Karen Chapple, the Mission is in a stage of “advanced gentrification.” The average income and rent have increased, while the non-white population in the Mission has shrunk from 71.8 percent in 1990 to only 57.3 percent in 2013. Incidentally, this date range echoes that of CAMP, which was founded in 1992 by two artists— performance artist Aaron Noble and Portuguese muralist Rigo 23— who lived in a refurbished cleaner’s on 47 Clarion.

In creating CAMP, they had manifold intentions: to beautify and create a safe space, to cultivate community and to provide an outlet for the diversity of voices in the neighborhood.

“The mural project has always been about being a voice for disenfranchised communities,” said Megan Wilson, who currently serves as co-director of CAMP but then frequented her friends’ pancake breakfasts at 47 Clarion.

CAMP took its first steps by getting permission to paint walls from building owners and seeking muralists. “Okay, so check this out,” an early flyer began, detailing how the early Clarion Alley muralists, like Carolyn Castaño, could obtain a $200 stipend for supplies.

In 1995, the same year Scott Winokur of the San Francisco Examiner described the alley as “a shooting gallery for dopers, a urinal for street people and an open invitation to a wrong turn for errant truck drivers,” Castaño, then a student at the San Francisco Art Institute, painted a portrait of salsa legend Celia Cruz on a doorway.

“It just felt really punk-rock or something, painting outside … kind of transgressive,” she recalled.

In 2000, the artists were evicted from 47 Clarion and the building was destroyed. Despite lacking a physical home, CAMP persists, organizing an annual block party and curating the constantly changing street.

This year, the alley hosts art that responds, intentionally or coincidentally, to the Trump administration. In addition to the SF Poster Syndicate mural, I saw a VOTA BERNIE red stencil during my March visit. On a corner by Mission Street, a crosshatched Trump waved a flag of nationalism and religion; the caption read, “Worldwide, there is a dark cloud on the horizon.”

These politicized messages stood alongside many others, like José Guerra Awe’s 2016 commentary on police brutality. “Rest in Power, Brothers and Sisters,” the mural read, in red, old-timey letters. He emblazoned an inverted American flag between the two lines of red text, complete with fifty golden sheriff’s stars. The black-and-white stripes of the flag contain an endless string of all-caps names of the Latinx and African-American victims of police brutality. Some names are nationally recognizable, like Sandra Bland; others are local, like Amilcar Perez-Lopez, shot six times at 24th and Folsom, only a five-minute bike ride from where we stood on the Valencia entrance to the alley.

Born in Belize, Guerra Awe “had never seen public art at this scale anywhere” before his then-girlfriend, now-wife, Alana Glassco, took him to Clarion Alley on a date. Now, he serves on the board of CAMP and told me stories about many of the murals the alley holds, from the oldest surviving mural in the alley (Chuy Campusano’s 1994 Guernica-evoking work) to his own.

As we talked, a red Fiat with a three-tier fake cake strapped to the top drove through the alley. Guerra Awe stopped and tapped at his phone— ever the artist, his thumbnails were covered with linear black and white patterns— to capture the only-in-the-Mission moment on Snapchat.

Directly across from Guerra Awe’s work lay another of the many murals with political messages, this one a 2015 collaboration with the Anti-Eviction Mapping project. Blown up purple circles surrounded a map plotting the city’s evictions. Each circle spotlighted someone evicted under the Ellis Act, which permits no-fault evictions if the landlord intends to stop renting units for a five-year period. The Mission District, per a report in Peninsula Press, has the highest Ellis Act and breach-of-contract evictions of any district in the city; such evictions bolster the narrative of the Mission as a poster child for San Francisco gentrification. Ironically, this anti-gentrification mural sits on the wall of the alley’s newest development, since it provides the nicest painting surface.

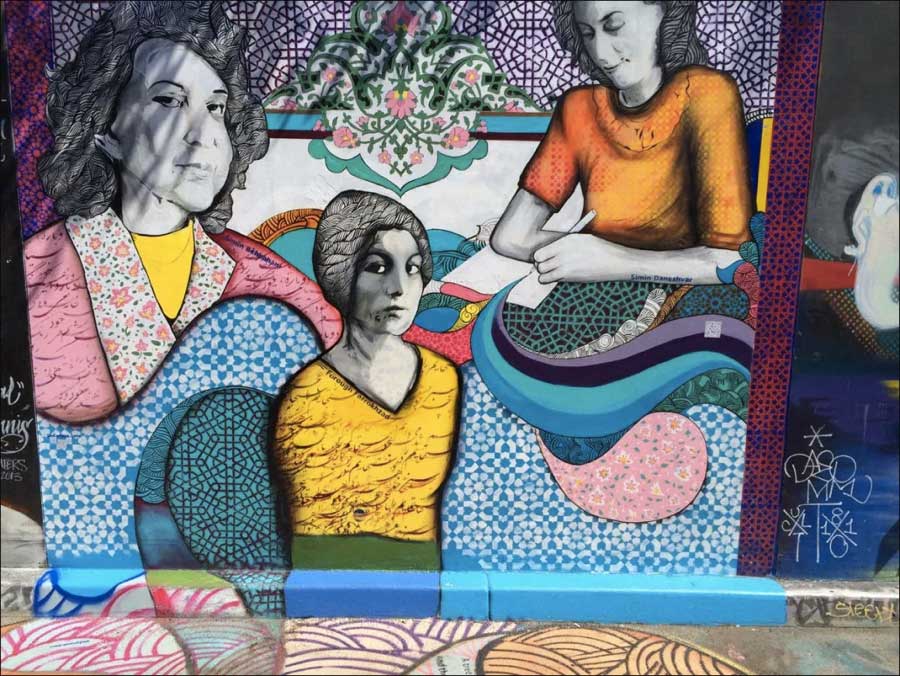

Further down Clarion, Keyvan Shovir, or CK1’s, 2015 mural depicting three Iranian female wordsmiths gained new political resonance in the wake of the election. Shovir is currently working toward an MFA at the California College of the Arts, but he’s also a foundational graffiti artist in Iran, where police took his street art designs as a signal of dissent. At 23, they arrested and jailed him for three days after catching him painting. After his fourth arrest and the Green Revolution of 2009-2010, he left Iran for America.

Shovir gained access to the Clarion Alley space after two years on the waiting list. Once he did, CAMP gave him and his partner Shaghayegh Cyrous a stipend of $120 — they spent it on falafel and then ended up paying around $500 out of pocket — and then began working with cardboard stencils and spray paint. His aim: to show his country in a positive light.

In the wake of the travel ban President Trump imposed through executive order, “My situation is exactly like a bird who left his house but his house is destroyed,” Shovir said. CK1 does not consider himself particularly political; he recognizes how here, his identity politicizes how others perceive his art.

With its plethora of politically and socially engaged murals, CAMP aims to spark conversation, but that doesn’t come without occasional conflict or misunderstanding. Self Edge, a jean shop down Valencia, uses the alley as a backdrop for photos of products like its 666 Devil’s Fit jean, which retails for $320, despite CAMP’s request they refrain from doing so. When asked for the rationale, employee Eugene Hood, working the antique-looking sales table, explained that there’s a “lot of history in Clarion Alley, and it fits our aesthetic with what we sell here.”

Another case of missing the message: Jose Guerra Awe recounted that people will point to a name on his wall — Michael, for instance — say, “hey, that’s me!” and then clamor for a photo. He tells them to look at the artwork as a whole, and asks, “let me know if you really want your name to be on this wall.”

Of course, not only hapless tourists illustrate the ethical quandaries Clarion Alley presents. For instance, artist Christina De la Cruz works at Apple and seeks to give back to the community and grapple with the privilege that allows her to do so through the process of creating her mural, a tribute to the city’s diversity that will include a quote from Black Lives Matter leader DeRay Mckesson. Guerra Awe’s wife Alana is a Stanford grad who works at YouTube, and her salary allows them to live in the Mission.

“I consider myself a gentrifier,” he said, even though often people think, “I get a bye because I’m brown.”

And, as Wilson and Statton pointed out, the social media apps that spread the murals’ message far and wide come from the tech firms many of the murals indict in the Mission’s gentrification.

While Clarion Alley and its sociopolitical context have evolved since a ragtag team of artists first decided to fill the street with color and message, the impact of the art remains profound. Statton, the co-director, has a favorite story. He was working on the recent “Housing is a Human Right” mural when someone approached him astride a bike. They asked about the mural (“Title unknown,” 2012) of the Compton Cafeteria Riot, a landmark in transgender history. The mural shows trans women leaders of the movement haloed, rendered as if the wall were stained glass in a church. The artist, Tanya Wischerath, was out of town and unable to repair it at the time, Statton told the biker.

At this point in the story, Statton’s voice broke. The biker, crying, had told him they passed the mural every day on the way to work. They were transgender, but coming out wasn’t an option at their workplace. They said the mural gave them strength to continue.

Christina de la Cruz, the Alley’s newest muralist, seems to have latched on to this truth quickly too. “[The alley]’s such a colorful thing, literally and figuratively,” she said. “It really does bring people together.”