When Parvin Bari bought her house near University Square Park in East Palo Alto 15 years ago, it was not in a floodplain.

So when she got a notice in the mail in late October saying her home was now at risk for flooding and must now purchase flood insurance, she was shocked. “That was the first time I heard about it,” she said.

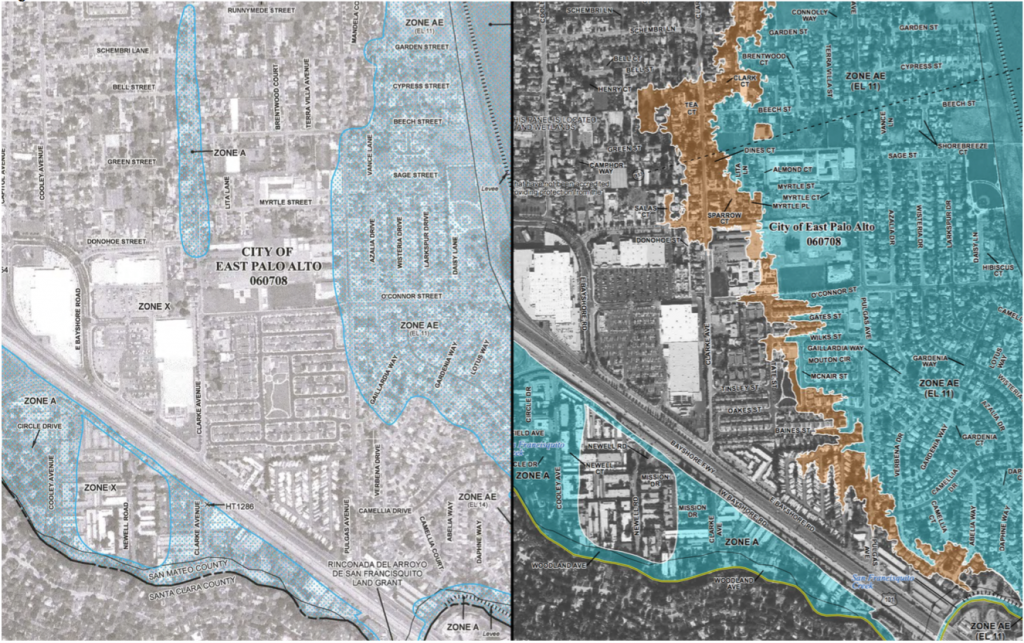

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has released Preliminary Flood Insurance Rate Maps, adding approximately 550 more properties to the East Palo Alto floodplain and forcing property owners with mortgages insured by the federal government to buy flood insurance. In the maps, about one third of the neighborhood surrounding University Square Park is in the floodplain, including Bari’s home.

East Palo Alto is situated on low-lying land between the San Francisco Bay and the San Francisquito Creek and has a history of flooding. Roughly 49 percent of city land is in the regulatory flood zone. The 1997 El Niño caused extreme flooding, and in 2012, when a high tide coincided with heavy rains, the area flooded again.

Notifications sent by the city to affected residents explained that some homeowners were required by federal law to buy flood insurance. These came at a time when anxiety is growing over expected flooding from another forecasted El Niño. Heavy rainfall from El Niño has high potential to overwhelm the existing levees along the San Francisquito creek this winter, and meanwhile, a flood prevention project that experts say would prevent some creek overflows hasn’t begun because of permitting delays.

FEMA maps

After Hurricane Katrina, Congress mandated FEMA reevaluate all U.S. coastal areas for flood risk. Since then, FEMA has been updating its previous flood risk maps using current information and modern technology. Often this means expanding the floodplain (the region at risk for flooding), and federal law requires that mortgaged homes in the floodplain have flood insurance.

In East Palo Alto, the cost of flood insurance for homes ranges from $450 per year to $4,000 depending on the level of risk, according to local flood insurance provider Jeri Fink’s State Farm office.

For most residents, the first notification of the changing maps was a city notice mailed out in mid-October like the one Bari received. Soon after receiving the notice, Bari attended an informational meeting held by the city, but, like many residents, she left still feeling confused. A few days later, Bari and another resident, Stan Jones, went to the city’s Community and Economic Development Department to meet with Project Manager Brent Butler in the hopes of clarifying the situation.

“I have a hard time believing that it is actually going to flood [in the newly added areas]” said Jones. Jones is not obligated to buy insurance because his mortgage is paid off, and despite his property being in the new floodplain he says he doesn’t plan to. “I am going to take my chances,” he said.

For mortgage holders, however, insurance is unavoidable. Different mortgage lenders may take different approaches, but one local lender, Raffi Soghomonian, explained that if a mortgage holder refused to buy the insurance, the bank would order it on behalf of the borrower and charge the homeowner.

However, according to Butler, residents can dispute their vulnerability status by getting an Elevation Certificate that determines a building’s freeboard — the distance between the base of a structure and the predicted flood height. The more freeboard, the lower the insurance costs.

However, Butler said residents should be careful. A certificate could backfire if it revealed that your home is more vulnerable than expected and resulted in more expensive insurance.

Butler also explained that residents still have an opportunity to receive reduced insurance rates. By buying insurance plans now instead of later next year when the preliminary maps have taken effect, residents will receive lower rates associated with their older, low-risk map status.

El Niño

At Jeri Fink’s State Farm office there have been more flood insurance purchases in the area in October than the rest of the year combined as homeowners buckle down in preparation for El Niño, according to Customer Service Representative Daisy Duong.

The city has provided some preparations for the expected flooding this winter, but much has been left to the residents to take care of themselves. Along with free sand bag distribution centers set up around the area, the city has also created an emergency notification system, raised a few sections of the San Francisquito Creek banks and cleared it of debris, and built a 400-foot-long temporary flood wall along Woodland Avenue.

These improvements, however, will not keep a storm comparable to that of 1998 from flooding the area.

Leticia Bullock, a lifelong East Palo Alto resident and parent of two, has been helping her mother Ruby Bullock, a retired senior citizen living alone, prepare for flooding. Ruby Bullock owns her home and has lived in the same flood-prone neighborhood of East Palo Alto for over 30 years.

“Some of the neighbors even have little boats they keep and use to get around when it floods,” Leticia Bullock said.

She recently purchased flood insurance for the first time in her life, paying $1,400 a year for her policy. Leticia Bullock has also helped her mother prepare an emergency flood plan, buy supplies, and soon they plan to get sandbags at a distribution center.

Delayed flood prevention project

A major flood prevention project, The San Francisco Bay Area to Highway 101 Project, could have potentially protected many homes from El Niño-related flooding had it been approved and completed sooner. The project has already been fully funded, and it was designed to bolster flood prevention measures along the flood-prone San Francisquito Creek. Nearly three years later the project still awaits approval and has not yet begun construction.

With funding already secured, the Bay to 101 Project was submitted to various state and federal agencies for approval starting in October 2012 by the San Francisquito Creek Joint Powers Authority, a collaboration of local city governments that heads flood prevention, ecosystem enhancement and recreational projects along the creek. According to Len Materman, the authority’s executive director, the Bay to 101 Project would significantly reduce flooding east of Highway 101 during 1998-scale storm.

“If the project’s regulatory permits had taken even one year to approve, construction could have been completed before the onset of El Niño,” Materman explained. “When implemented, the Bay to Highway 101 Project would significantly reduce the effects of a storm greater than what we’ve ever seen on areas east of the [101] Freeway.”