The heated backlash over low immunization rates in select California counties has authorities talking heavy-handed legislation.

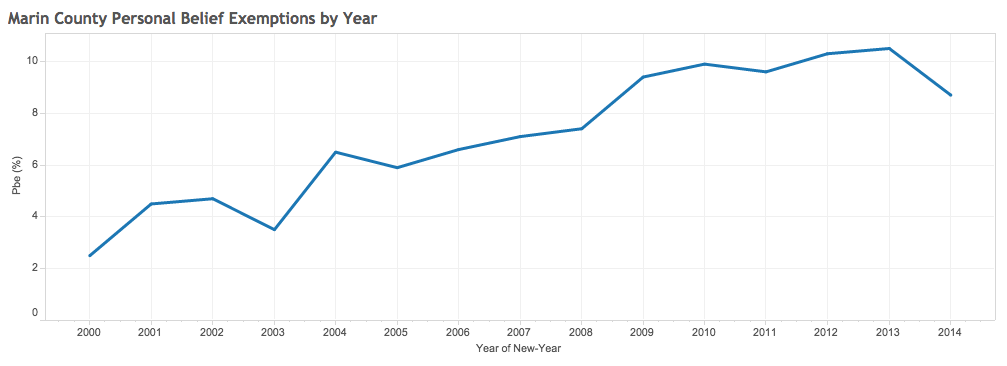

A January study through Kaiser Permanente identified Marin County as one of five “clusters” of high under immunization in Northern California. Contributing to low immunization rates in the county are personal belief-based exemptions. Overall Marin County personal belief exemptions are exceptionally high, averaging over 8 percent compared to around 2 percent for California as a whole.

At San Geronimo Valley Elementary, a small Marin County school, just three kindergartners out of a class of 19 have been immunized for the current school year, according to data from the California Department of Public Health. The school’s personal belief exemption rate is 58 percent, or 11 out of 19 kindergartners.

In response to clusters of high exemption rates across the state, local Sacramento-based Sen. Richard Pan (D) has joined with Sen. Ben Allen (D) and Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez (D), to introduce a bill to end belief exemptions completely.

“When a parent’s decision to ignore science and medical fact puts other children at risk, we can’t as a state condone it,” Gonzalez wrote in a press release introducing the bill.

But some experts caution against extreme legislation that may be emotionally charged. David Ropeik, a consultant on risk perception and risk communication, called the elimination of exemptions for vaccinations “a step too far,” in a February opinion piece for the Los Angeles Times.

“It’s what we tend to do when we’re afraid,” he wrote. “We react with emotion first and careful thought second, sometimes at great societal cost to civil liberties.”

Statistics from the California Department of Public Health suggest extreme legislation may not be necessary. Despite above average numbers, exemption rates in Marin County have come down from highs of over 10 percent across the last two school years.

In addition to personal belief exemptions, parents also opt out of immunizations for medical and religious reasons. Exemption rates are of particular concern when it comes to measles because of the highly contagious nature of the disease.

The “herd immunity threshold,” or the coverage needed to prevent the disease from persisting in the population, is around 93 percent for measles, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. To watch how measles spreads within under-immunized communities, check out The Guardian’s interactive graphic.

Personal belief exceptions are now banned in 32 states. If passed, California’s version of the legislation would also require schools to notify parents of immunization rates at their schools to encourage community awareness of the issue.

Locally, Superintendent of Marin County Schools Mary Jane Burke is championing the cause. She says she is taking “a hard stance on the importance of vaccinations for anyone who is medically able to do so.”

In a letter sent to all parents of children in Marin County Schools, Burke also focused on the effects one parents’ choices may have on “the greater good” of the community.

“While parents may have the statutory right of refusal, they do not have the ethical right to expose others to their children’s lack of protection,” she said. “In other words, having the right to do something does not mean it is always the right thing to do.”

…Having the right to do something does not mean it is always the right thing to do.

James Wheaton, a Berkeley attorney who specializes in First Amendment rights, says the state legally has the power to require every student to be vaccinated in order to attend school, both public and private, without exception. As examples, he points to the state’s right to quarantine sick and infectious people against their will and to require drivers to carry current driver’s licenses.

“Particularly with regard to public health, authorities have a lot of control,” Wheaton said.

(Editor’s Note: Wheaton is a visiting lecturer in the Stanford Journalism Program.)

Despite government’s legal ability to ban exemptions, experts say heavy-handed legislation may only compound matters.

Ropeik believes milder legislation, such as increasing the burden on parents to opt-out, may suffice. In Washington State, he says, exemption rates dropped 25 percent after parents were required to provide evidence that they were educated on the issue.

An existing California law, which went into effect Jan. 1, 2014, requires parents to speak to an authorized health care practitioner about vaccines and diseases before receiving a belief exemption for their children.

Recent high-profile coverage of under-immunization in the midst of a growing measles outbreak has triggered heavy backlash across social media. Some parents (and even doctors) who have defended their choices not to immunize their children in the media are taking a viral beating.

Last month, high-profile blog, The Daily Banter, criticized Arizona cardiologist Dr. Jack Wolfson for his stance on vaccinations, calling him, “a cartoonishly villainous anti-vaxxer who openly admits that he doesn’t care whether his decisions as to how to parent his own child put other people’s children in danger.”

Saad Omer, an associate professor of global health at Emory University, favors higher burdens over bans. “[Heavier burdens] will cost taxpayers money,” Omer wrote in a February opinion piece in The New York Times. “But they will be more effective in the long run, than condemning vaccine skeptics as ignorant and irresponsible.”

In a 2012 study published in The New England Journal of Medicine, Omer found parents were 2.5 times more likely to vaccinate their children in states where they faced exemption procedures that were more time consuming.

Other research isn’t as clear cut. Brendan Nyhan, assistant professor of government at Dartmouth College, evaluated the effect of increased education on measles, mumps and rubella vaccination rates, reporting mixed results in a nationwide study.

Nyhan said he found that telling parents the vaccine doesn’t cause autism did successfully reduce belief in the myth itself. However, it also made parents with the least favorable attitudes less likely to vaccinate, rather than more.

“Our interpretation is that people often respond in a motivated way to disconfirming information. When you’re told you’re wrong [about a reason], you tend to think of other reasons you’re right.”

Still, Nyhan said mandates for additional education in order to get exemptions may still be effective. Although the information provided to parents most disinclined to vaccines may not have the intended result, Nyhan said the additional burden of having to visit a doctor could motivate the majority of the population.

“It’s not to say that education is helpless or pointless,” Nyhan said. “…Even if information has no effect, it may be that making it more costly in terms of time to get an exemption may help.”

(Homepage photo courtesy of James Gathany/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; caption: a 3-year-old boy receives an immunization injection.)