It’s Monday and TJ Johnston is on deadline. Four days from now, he’ll file his piece, and then spend the next few making tweaks with his editor in preparation for the Feb. 1 edition of Street Sheet, a bi-monthly newspaper covering homeless issues in San Francisco. The final layout will likely extend to the early morning hours of the 1st, but as long as it reaches the printer by 6 a.m., the issue will drop on-schedule.

Along with being Street Sheet’s go-to reporter and associate editor, TJ Johnston has another important priority: finding a place to sleep. He’s been homeless for almost six years.

Johnston looks up from his laptop, his Caribbean-blue eyes peering past the brim of a black ball cap. He’s dressed in a hoodie and jeans, and despite the silver hair that covers his ears, Johnston, who turned 50 last May, retains a boyish quality.

For his article, Johnston plans to interview San Francisco’s four new supervisors about the ongoing homelessness crisis. The latest count estimates the population at nearly 7,000 people. In November, voters shot down legislation that would have raised nearly $70 million for more shelter and supportive housing. Where the funds will come from now remains unclear.

This is what Johnston wants to ask the supervisors about. Along with Mayor Ed Lee, the 11 district supervisors, or “Supes” as he calls them, are in charge of allocating San Francisco’s $9.5 billion annual budget. But the Supes can be hard to pin down. Johnston says it might take four or five emails to aides and other gatekeepers to schedule an interview.

So far, he’s managed to get one on the line – Hillary Ronen, the young Berkeley Law graduate who now represents District 9, the Mission. To meet his deadline, Johnston will need to get a hold of the remaining three by Friday afternoon.

[dropcap letter=”S”]treet Sheet’s newsroom occupies a three-desk enclave embedded within the Coalition on Homelessness, the paper’s nonprofit sponsor, in the heart of San Francisco’s gritty Tenderloin District.

In some ways, it resembles any other newsroom. There are the back issues stacked on over-stuffed shelves, notepads scribbled with shorthand strewn across desks and the dry-erase editorial calendar. On closer inspection, the office’s ramshackle charm extends beyond peeling paint. Ceiling tiles show patches of water damage. Missing doorknobs have been replaced with latches and padlocks.

“I’m basically your typical, mild-mannered reporter,” Johnston replies with self-deprecating wit, when asked about his role at the paper. On any given topic he might quote Ernest Hemingway, Napoleon Bonaparte or the comedian George Carlin. And like a well-seasoned reporter, Johnston chooses his words precisely, careful not to misrepresent himself.

Sam Lew, Street Sheet’s chief editor, is less restrained when speaking of his contributions. “TJ is amazing,” Lew said. “He’s the person I go to when I have questions.” As editor, Lew tries to remain as invisible as possible, letting the voices of people experiencing homelessness speak for themselves.

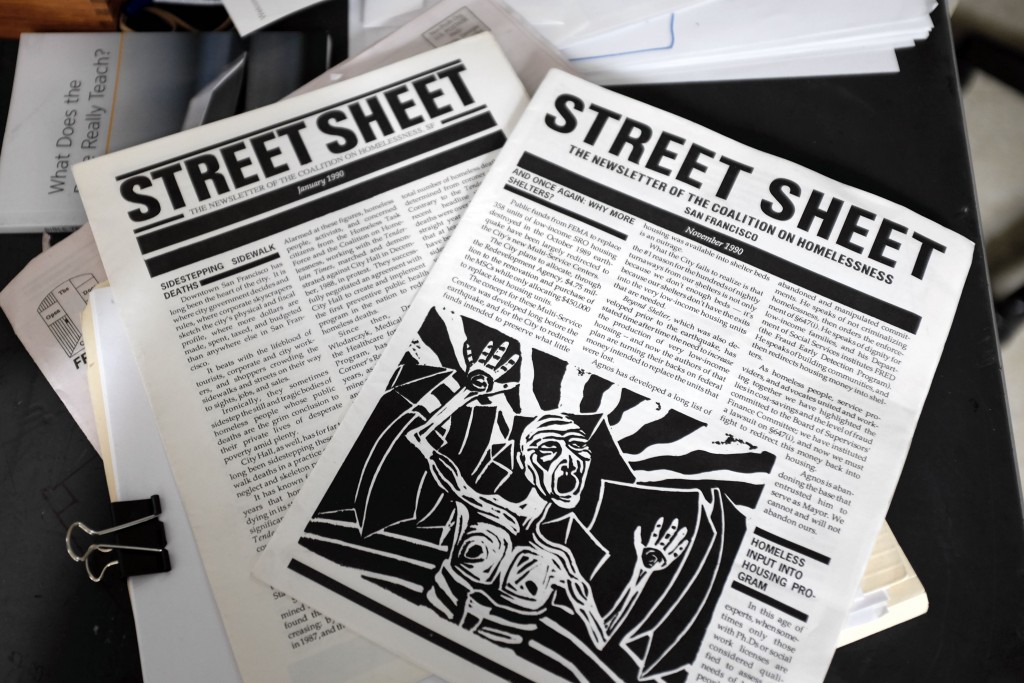

Nearly every aspect of Street Sheet’s operation embodies this philosophy. Most contributors are homeless themselves, as are the 240 vendors that sell the paper on street corners for two dollars an issue. For many, it’s their only source of income. Despite ups and downs with circulation, the model has worked. Street Sheet, which launched in 1989, holds the distinction of world’s longest-running street newspaper.

Johnston hopes his reporting can help dispel pubic misconception about the homeless.

“They shouldn’t be defined by their situation,” he said. “Homeless people have these lives that preceded their loss of housing.” It’s a narrative Johnston knows well. Like many homeless San Franciscans, he lived and worked in the city before landing in the streets.

Johnston describes the descent with a line from Hemingway’s “The Sun Also Rises”: “It happened ‘gradually, then suddenly.’”

[dropcap letter=”A”]fter graduating UMass with a theater degree, Johnston moved to San Francisco. For years, he scraped by with odd temp and office jobs. Then in 2000, he found his calling in journalism at a writing workshop taught by Adam Clay Thompson, a reporter for the San Francisco Bay Guardian. The class’s final project, an exposé on corrupt nonprofits called “Poverty Pimping,” ran in Street Sheet.

Johnston has been a reporter ever since, writing for similar publications around the Bay Area, often with a focus on homelessness. But it wasn’t until 2011 that he experienced it first-hand. A few years earlier Johnston had been laid off from his day job conducting phone surveys. Once his unemployment benefits expired, Johnston could no longer make rent. He was 44 years old.

Since he isn’t a veteran and doesn’t have a disability or substance abuse problem, Johnston can’t qualify for most government services offered to the homeless. He could enroll in the county’s welfare program, but that would prevent him from accepting paid writing gigs. For his contributions to Street Sheet, Johnston receives Safeway gift cards.

For now, shelters are his best option.

At the moment, he’s finishing a 90-day stint at a shelter across town run by Dolores Street Community Services. When the reservation ends, he’ll put his name on the waiting list for another 90-day bed, but it usually takes four to five weeks for one to open up. This means for the next 30 days, Johnston will spend hours waiting in line outside a day-by-day shelter for a cot to crash on for the night. This cycle will repeat itself many times.

The process is dehumanizing and bureaucratic, and makes it nearly impossible for people like Johnston to hold down a job or navigate a permanent exit out of homelessness. Somehow, Johnston musters a little perspective on the matter.

“It’s a lot like going to the DMV,” he said, “Except without the sensitivity.”

[dropcap letter=”A”]t the shelter, Johnston keeps his head down. To get by, he compartmentalizes: it’s a place to shower and get some sleep. His real life is lived during the day, in the offices of Street Sheet.

Over a cup of coffee on the morning of his deadline, Johnston reveals how he spends the Safeway cards he earns working on the paper. Instead of groceries, he buys Starbucks gift cards so he has a place to write when the Coalition’s doors are closed. He even carries around an empty coffee cup in case he runs out of cards and needs to prove he’s a customer.

Despite the economic challenge, Johnston remains committed to educating the public on homelessness. “I want to continue fighting the good fight,” he said. As Johnston sees it, journalism offers him his best shot.

There are signs that Johnston’s efforts are paying off.

In July, The San Francisco Examiner commissioned him to write two articles as part of SF Homeless Project, a collaboration of 70 media outlets to help find solutions for homelessness. Sick of hearing from city officials and so-called experts, Michael Howerton, the Examiner’s editor, reached out to Johnston for the perspective of a working journalist who was also grappling with the issues.

“I wanted to get someone from the front lines into the pages,” Howerton said. “I thought that his work was some of the best of the whole project.”

Back at the office, TJ Johnston sits down at his desk and opens his laptop. His deadline is 5 p.m., and he’s managed to line up an interview with another supervisor – Jeff Sheehy, the former HIV activist turned District 8 representative. The Supes haven’t told him much. But it’s enough for Johnston to go on.

CLARIFICATION – Editor’s Note (4/17/2017): This story is updated to clarify the chronology of Johnston’s biography and to include the full name of Dolores Street Community Services.