This ski season in Tahoe City, Calif., has had the typical indicators of a popular ski town: crisp winter air, thousands of tourists flocking to some of the country’s most famous resorts, and of course, a blanket of powdery white snow. But skiers have been disappointed to find that the usual thick blanket has become more of a threadbare throw.

Due to California’s infamous drought and climate change, Tahoe is experiencing record low snowpack which has drastically affected the ski experience. Both competitive and recreational skiers alike have noticed the negative impact.

“I’ve been skiing Squaw my whole life, and I’ve definitely noticed a decline in snow levels in recent years,” said avid skier Andy Meislin. “Growing up, I remember having contests with my ski team friends over who could sit in the snow longer before needing to run back into the hot tub and jump in. The last few years, you couldn’t have that contest if you tried due to lack of snow.”

James Price, a former member of the Stanford Ski Team, didn’t even join this year due to lack of snow.

“I didn’t join because … the financial cost was just too big an investment if it wasn’t going to snow enough to make the mountain really ridable,” Price said. A season pass wasn’t worth the price either. “Skiing is an incredibly expensive sport so I didn’t think buying a season pass in Tahoe would be worth it with such a meager amount of snowfall.”

Others involved in the ski industry are suffering due to low snowpack levels. To compensate, ski resorts are closing for weeks at a time, opening later, and some are manufacturing artificial snow. Even these solutions might not be enough, however. Instead, resorts are looking to activities unrelated to snow such as zip-lining and mountain biking as a way to draw customers.

“We have to get our heads out of the snow,” Boreal’s general manager, Amy Ohran, said in an interview with The New York Times. “A lot of discussions are about seasonal diversity, and expanding revenues in areas that are not dependent on snow. Our hearts are in skiing and snowboarding, and we want to see that succeed. But we have to cast a bigger net.” Ohran could not be reached for comment.

Undoubtedly, the changes in snowfall are the result of climate change, say those in the ski business.

“I don’t know of anybody in the industry who is saying that climate change is not an issue for us,” said Bob Roberts, president and chief executive of the California Ski Industry Association. “If you’re below 6,000 feet, it’s a real challenge.”

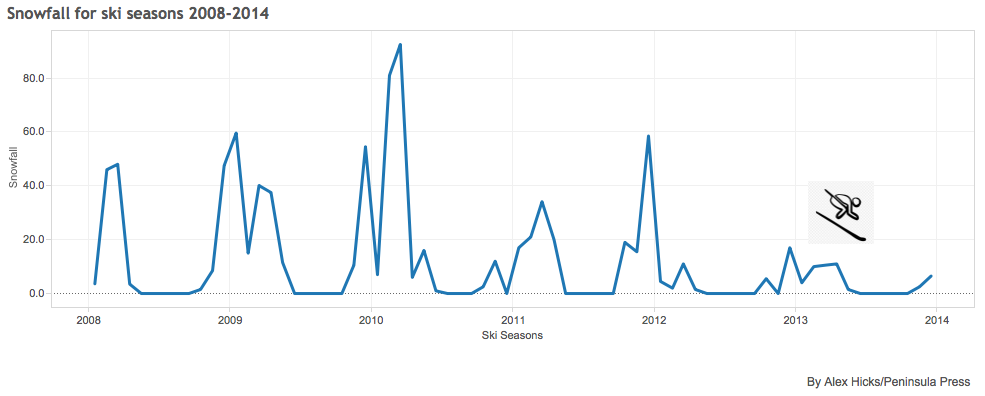

One dry year might not be cause for concern. But over the past three years, snowfall has been on a steady decline in Tahoe. While most yearly snowfall totals have been in the high 100 inches or early 200s, snowfall was a mere 41.5 inches in 2013. Last year was no better, totaling 46 inches in 2014. And with the record-breaking drought, 2015 appears to be following suit.

Snowfall totals have been declining over the last century, according to data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

“The past two winters have set new records for warmth in the Sierra Nevada and much of the 21st century has averaged temperatures higher than the period of record mean,” said Michael Anderson, a state climatologist for the Department of Water Resources.

“Expectations are for this … to continue with more new records being set as climate change progresses.”

Over the course of the last 114 years, just six years — 1924, 1934, 1947, 1976, 1987 and 1991 — had snowfall of less than 100 inches. Of those low years, the lowest level was 54.9 inches of snow, and each instance was at least 10 years apart. Until 2013 and 2014 that is.

The lack of snow is notable, said Georgia Toal, captain of the Stanford Ski Team and a native Oregonian.

“Everyone talks about how great Tahoe is for skiing,” Toal said. “But ever since I’ve been in California, I can barely make it down the slopes without having to hop over a few rocks.”