“I get overwhelmed,” AJ Cramer talks about his experience as someone with hearing impairment on TikTok. His family of six is hearing, and he often finds himself struggling to keep up with the conversations at home.

“I’m the one who[’s] left out most of my life because I have NO idea what they’re talking about. I love my family and I hate to miss out on anything! Like how they do at school,” he said.

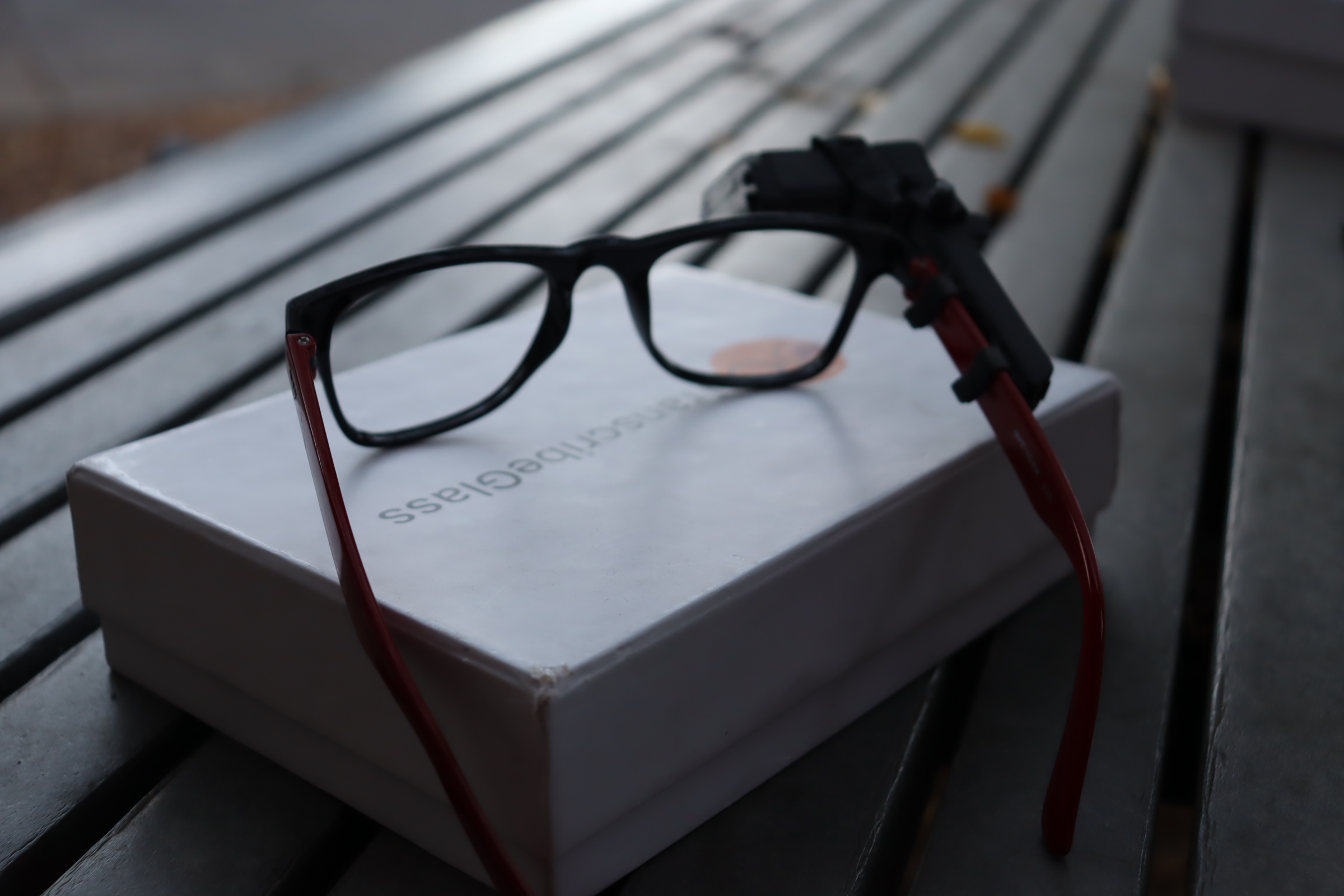

One day, his 16-year-old daughter Novalee sent him a TikTok video that could solve this problem. The video, which has more than 18.1 million views, shows a pair of glasses that provides subtitles for the real world.

While almost 10,000 people are on the waitlist for TranscribeGlass, Cramer created a Tiktok video explaining how the glasses could make him feel more comfortable and able to more easily participate in conversations.

“I’ll be able to go out, have fun, and not be isolated at home. I just want to be ME without depending on people. Or write on a piece of paper with so much waste! I just need this in my LIFE! I’ll be crying if I get it!” Cramer wrote in an email response.

Entering its third year of business, TranscribeGlass plans to first tackle the challenge of meeting the astronomical demand. Co-founder of TranscribeGlass Tom Pritsky’s voicemail and inbox are flooded with questions about how people can join the waitlist and when they will receive their glasses.

“We have been bootstrapped for a really long time, but I think now and in the next year is time to really accelerate. We have such a massive waitlist now, and we really want to meet that demand quickly,” he said.

So far, there have been five prototypes made and over 300 users had the opportunity to try on the product. Starting early next year, the company will send the transcription glasses to a small batch of users on the waitlist, and an even larger consumer batch later in the year.

Commercialization of this scale is not common for startups in the assistive technology space. Research identified the lack of user involvement during the design process as the main reason why people abandon their assistive devices. Even if the product has some benefits that improve quality of life, it often falls short of meeting the user’s needs.

David L. Jaffe, adjunct lecturer teaching “Perspectives in Assistive Technology” at Stanford, explains the challenges of commercializing assistive technology.

“Companies who are making devices want to make millions of them, sell them to millions of people, make them all the same. But, people with disabilities are individuals. And each person with a disability has very specific challenges and preferences,” he said.

When Jaffe asked a professor (now retired) with hearing impairment if he would like to try out TranscribeGlass, that professor refused. After living a life using all the hearing aids that didn’t work for him and the progressive disease, he preferred not to deal with assistive technology anymore.

Rachel Kolb, a deaf and disability advocate and junior fellow at Harvard University, underscores the challenge for assistive technology to universally address accessibility issues. She’s used various assistive technologies for her entire life, including hearing aids, cochlear implants, and teletypewriter.

“Technology isn’t a panacea or a silver bullet for accessibility, meaning it won’t provide ‘full access’ to every situation for every person who decides to use it. The situations we place ourselves in are so complex and variable, and we’re all so different,” Kolb said.

TranscribeGlass has attended two Assistive Technology Fairs hosted by Jaffe. Despite the variety of preferences individuals have concerning assistive technology, Jaffe sees the device’s potential to benefit a lot of people.

“It’s pretty neat. Having more choices out there is always better, right?”

To meet the increasing demand, the company needed additional funding from investors. The consumer hardware sector presentsa challenging climate for startups because the iteration cycles are longer. It’s a capital intensive process. Still, Pritsky is not concerned about the funding.

“We have gotten agile funding today, which has been helpful. In addition to supplementing the grants, we really want an investor who understands the mission,” he said.

Additionally, there is the reality that hearing loss is ubiquitous. It’s a disease of old age that many people would experience in their lifetime, like diminishing vision. About 15% of adults in the United States have some trouble hearing.

“Everyone has someone who has a hearing loss in their family, friend. They’ve been touched by it. Finding that resonance of ‘I get what you’re trying to solve’ has really helped us strike a chord more quickly,” Pritsky said.

Other factors contributing to the success of TranscribeGlass include categorization and price. On average, it takes 3 to 7 years to bring a medical device to the market through FDA approval. Instead of labeling TranscribeGlass as a medical device, it’s labeled as a technology product, and they don’t have plans to seek FDA approval in the near future.

“It’s not a hearing aid per se. It’s an accommodation that gives you subtitles for the real world. The primary driver for us to get FDA would be to get insurance to pay for this. And since insurance doesn’t pay for hearing aids, it doesn’t make sense to go through that effort,” Pritsky said.

Medicaid, a joint federal and state health coverage program, for instance, covers hearing aids for mostly individuals under the age of 21. The policy might differ for adult residents of Alaska, California, Connecticut, Florida, and Hawaii.

For individuals with severe hearing loss, the absence of insurance could mean paying on average $2,500 for prescription hearing aids. For those with mild to moderate hearing loss, over-the-counter hearing aids range between $300 to $600. TranscribeGlass, on the other hand, has a starting price of $55 for its beta model and estimated price of $95 for the final model.

The affordable price stemmed from how TranscribeGlass started. It was designed for someone who couldn’t afford hearing aids. The person didn’t enjoy looking down at an app on his phone because he wanted to engage with the person speaking. The user-friendly nature also reflects on its durability.

Mark Zuckerman, one of the first people who tried on TranscribeGlass in its prototype stage, reflects on his experience.

“I had a piece that came off and Tom just talked me back into gluing it. It’s very fixable. You can bang it around. When I first got it, I was super delicate with it, but you don’t really need to be.”

At work, Zuckerman uses the auto caption feature on video conference platforms for transcription. When he’s with family, he finds opportunities to use TranscribeGlass. While doing the dishes with his phone connected to the transcription glasses, he can see what his partner, who is physically in another room, is saying.

Data collected by the World Health Organization suggests that globally over 30% of people have trouble affording assistive technology. Another barrier to accessing assistive technology on the list of reasons is social stigma.

Pritsky, who has had bilateral hearing loss since 3-years-old, relates to the struggle. He is currently taking a leave of absence from his master’s program in biomedical informatics at Stanford to focus on the company.

When he started studying at Stanford as an undergraduate student, he would wear his hair long to hide the hearing aids and wouldn’t tell people about them. Social stigma is a blocker for hearing aid adoption for some people.

“I realized that’s not a great idea,” he said. “I’m fairly confident that there is significantly more acceptance of glasses based form factor than a hearing aid form factor, just socially for some reason, likely because that vast majority of people already use glasses.”

TranscribeGlass isn’t the only one receiving large amounts of acknowledgement in the smart glasses business. Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, and Google have similar products with assistive features.

Back in October, Meta released its collaboration with eyewear brand RayBan. Their smart glasses allow users to listen to music, live stream, and take calls. And about a year ago, Google’s augmented reality translation glasses exhibit the possibility of breaking down language barriers. However, the product is allegedly on freeze as the company puts more focus on their software products.

Companies on a smaller scale like XRAI and Xander also offer transcription glasses, yet at a higher cost, up to $4,999.

Amid the competitive landscape, TranscribeGlass pays attention to bettering the user experience and meeting the demands of 10,000 people. Its user-friendly nature throughout the design and pricing fuels the business’s ongoing growth. In the end, optimal outcomes in the assistive technology business thrive with an abundance of choices.

“As long as we don’t lose sight of the maxim ‘one size doesn’t fit all,’ and as long as we keep on learning new ways to engage with each other, including through ASL, all of this is a potentially very exciting tool to have in a larger toolbox,” Kolb said.