SAN FRANCISCO — It’s 6:45 a.m. on a Tuesday in early December, and 47-year-old Arlen Arosteguis has 15 minutes to move the home where he, his wife and two young children live. He opens his garage and stuffs in the few of his belongings that remain: a small heater, the trombone he left out the night before, his folding table.

He hasn’t seen his neighbor this morning, so he runs over and pounds on their door. “¡Llegarán pronto, tenemos que irnos!” Arosteguis shouts. “They will be here soon, we have to go!”

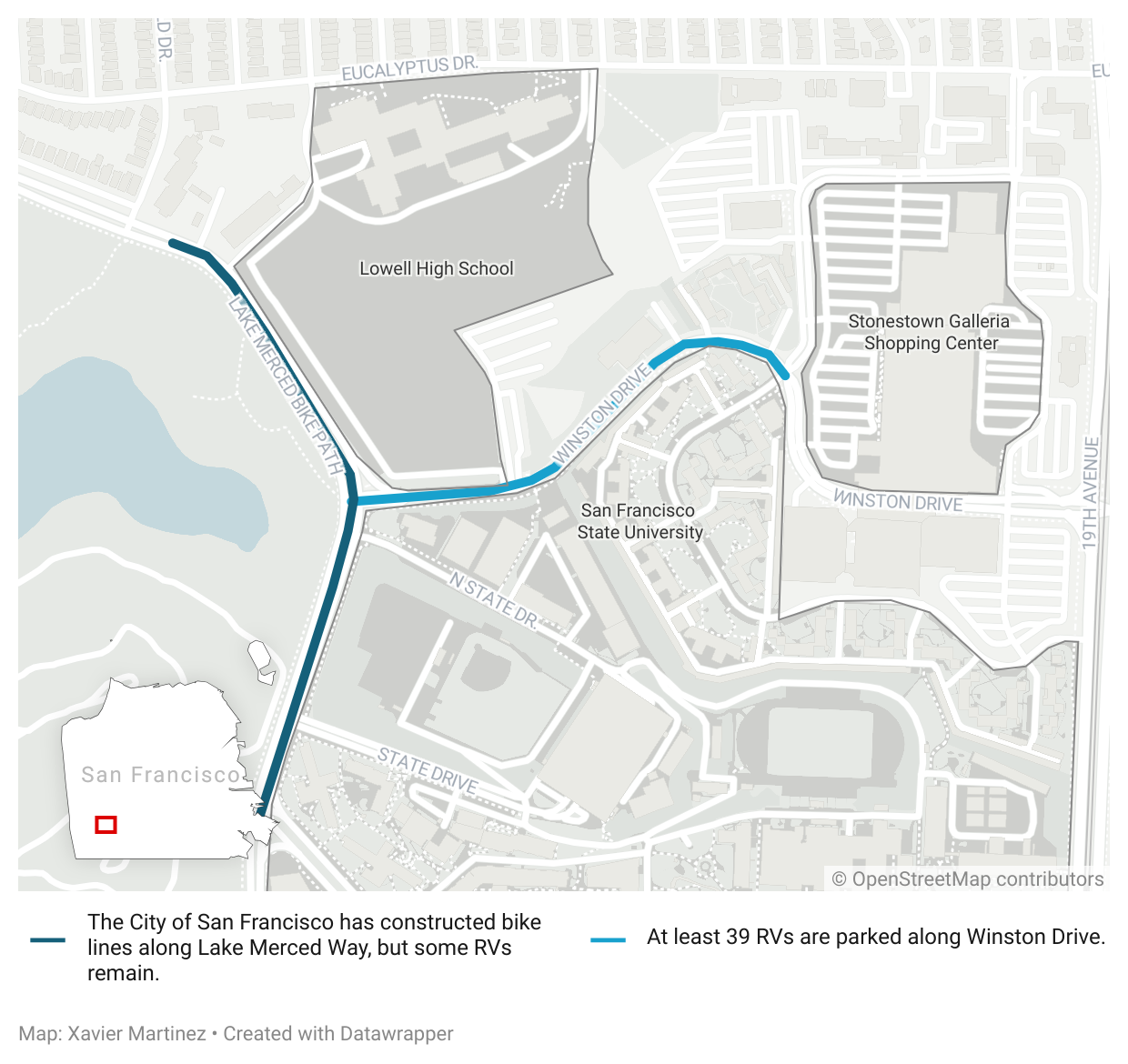

Arosteguis is one of about 100 people who live in RVs parked on Winston Drive near Lake Merced, on the west side of San Francisco. His garage, a small compartment along the left side of his vehicle, holds the portable heater and an electric generator that most residents use to stay warm during cold nights that hover near the freezing point. His patio is a few rectangular chunks of faux grass.

Arosteguis starts his RV at 7 a.m. nearly in unison with the dozens of RVs parked along the street – 19 on the north side and 20 on the south. For the next hour, the residents drive their vehicles around the Stonestown neighborhood, stopping at the large shopping mall nearby or a McDonald’s a few blocks away, as they stay out of the way of the city’s street cleaner. A few people stay behind and stand sentry. They ensure that, once the cleaner leaves, nobody else sneaks into the coveted spots.

An hour later, the RVs return, and Arosteguis glides into the same chunk of curb that he jokes is his property. He has avoided a $90 parking ticket, an expense that he cannot afford. Just as quickly as the community came together to evacuate the block, it dissipates. Residents trickle out of their RVs, walking to bus stops or getting in their cars, and start their trek to work.

These street cleaners come every Tuesday morning, so the predominantly Latino group of around 100 people have built the movement into their routine. But residents are concerned that upcoming changes to city policy means they will lose that community.

Four-hour weekday parking limits that were announced last September by the San Francisco Metropolitan Transportation Authority are set to go into effect on Dec. 19, less than a week before Christmas.

The restrictions are the latest in a months-long process by San Francisco to identify the residents, search for other parking sites, and find permanent housing for the community. Winston Drive is one of several corridors where RVs have recently found a place to park in groups, only to be pushed out by parking restrictions. In early November, the SFMTA removed RVs on the east side of Lake Merced Boulevard.

For families like Arosteguis’, who lived in an apartment before the pandemic struck and money dried up, the parking changes feel like another eviction – another embarrassment.

“We have our little children,” Arosteguis said in an interview. “It’s almost Christmas, and even though we’re living on the street, we have a dream for our families.”

The planned parking restrictions would effectively put an end to that dream, Arosteguis said.

Despite setbacks, residents advocate for safe parking sites

Supervisor Myrna Melgar, who represents the area, requested in July that SFMTA enforce parking restrictions along Winston Drive. Two pedestrians have been killed by motor vehicles in the area in the past two years.

“We have let the situation persist for many, many years,” Melgar said in a Sept. 19 SFMTA meeting. She added that besides restricted pedestrian visibility caused by the large RVs, their use of gas-powered generators pose a fire risk and inconsistent disposal of sewage poses a public health risk.

For months, residents, government officials and advocacy groups have searched for solutions. In a Dec. 8 presentation to the Homeless Oversight Commission, Executive Director of San Francisco’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing Shireen McSpadden noted that the city has been looking for a safe RV parking site for nearly two years, and that the city was close to locating a viable location. San Francisco has used pop-up safe parking sites in the past at the Balboa Park BART station and in the Bayview neighborhood, but some – including residents of those sites – have criticized them for being poorly managed and dirty.

In 2022, Mayor London Breed cut $6 million in funding that would have gone to a safe parking site, using the money instead to support some of the 4,397 people who were homeless and unsheltered.

“We have been very clear [to the SFMTA] about needing more time to work with the families that are out there,” McSpadden said during her presentation, suggesting that residents could be allowed to park along Winston Drive for longer than anticipated.

Comments like McSpadden’s give hope to organizers like Javier Bremond, who works with the Coalition on Homelessness, that enforcement will be limited.

Kiko Suarez, who has lived in an RV along Winston Drive since the beginning of 2023, believes that the city won’t enforce the Dec. 19 decision, but will evict the residents at some point.

“There’s a lot of people who are anxious about the move,” Suarez said in an interview. “We’re feeling a little bit more comfortable that it’s not going to happen soon…but I think we’re going to lose at the very end of the day because that’s what the city wants.”

As of Dec. 11, no city official has indicated whether the SFMTA will enforce the Dec. 19 restrictions as planned.

Many of Winston Drive’s residents can’t attend city commission meetings and miss government outreach events, which often happen during the workday. Some work odd hours, others ride public transportation for hours per day, and most have families to take care of back home at Winston Drive. Victoria Oliveras, a 21-year-old Brazilian immigrant, leaves at 5 a.m. to catch the bus that takes her to Marin County, where she works. When she returns home, she applies to other jobs, or goes to sleep in preparation for another early morning.

But a group of the RV residents attends monthly transportation and homelessness meetings, encouraged by advocacy groups like the Coalition on Homelessness and the Glide Foundation.

Deisiene Pereira, who only speaks Portuguese and lives with her two children in an RV on the South side of Winston Drive, asked for empathy.

“I’m asking you to put yourselves in our place,” Pereira said to the Commission on Dec. 8. “What if you were living in a motorhome and you were told to leave? What would you do?”

Another resident, who identified himself as Leandro, said that he had lived in an RV on Winston Drive for a year and a half. Originally from Brazil, he said that the stability had allowed him to adapt to the region.

“It’s not the most comfortable situation to live in a motorhome at this moment, but that’s all we can do,” he said through a Portuguese translator. “We’re happy there.”

And Arosteguis, who works full time as a tow truck driver, drove to San Francisco City Hall, parked in the lot, passed through the security line, and asked for a hand.

“We are looking for help to find a parking spot. That is all,” Arosteguis said.

One night on Winston

Kiko Suarez returned to his RV around 6 p.m. after a long Monday practicing his art. With his income reduced while on workers’ compensation after a head injury at a construction site, Suarez had decided to learn to become a tattoo artist— a lucrative business that can pay more than $100 per hour, his friends in the industry told him. These days, he spent most of his time at Peet’s Coffee drawing designs or practicing his technique on synthetic skin.

It felt colder inside than the December air outside. Suarez wedged his way through the vehicle, past the table and between the two chairs, until he got to the passenger seat. He had left his window open throughout the day, and the generator he used to keep RV warm enough to sleep in was out of gas. He sighed, got on the motorcycle that a friend lent him after his RV had broken down, and left for the gas station.

The sound of the motorcycle caused Arosteguis and his brother-in-law, Miguel Espinosa, to turn their heads. The brothers – also next-door neighbors – often sat in lawn chairs after a long day of work, resting their feet on the turf that they had turned into their lawn as they smoked cigarettes and sipped wine.

Arosteguis rarely felt proud of his vehicle, which he described as a “simple, thin aluminum sheet.” But, after a long day, he was glad he had the RV for his children to rest before school the next day. For him to be off his feet after a day of driving tow trucks, if only for a few hours.

He wasn’t sure if these nights – when the family could relax without thinking of where they’d park the next day – would continue. Arosteguis knew that he and his wife were too busy to move the RV every four hours to comply with the new parking restrictions, and he didn’t know of another spot where they could park for multiple days.

But his brother reminded him of their philosophy. “Do not stay idle. Have a positive attitude and move forward, Espinosa said. “See the future; see it for your children.”