With the decision to sit indoors or out, Mark Purdy chooses the latter. Noises of an approaching San Jose spring fill the air: the loud hum of a lawnmower, nearby chitchatters, staccato jingles from a dog’s leash. He wears pitch-black, thin-framed rectangular sunglasses and, beneath a beating sun, sips on a medium hot chocolate topped with whip.

Purdy remembers the first time he saw a webpage in the San Jose Mercury News office in 1995. Now, he posts his columns online and shares weblinks in his tweets that only get clicked on 10 percent of the time. This year, he will turn 65, and, after nearly five decades as a sports writer, he is leaning toward retirement sometime this summer.

“I just never feel the job is over. And I always feel as if I’m doing the wrong thing.”

He’s become, as he says, “the grumpy old guy in the press box.”

The beginning

Purdy grew up on the Ohio-Indiana border in a town called Celina (population: 7,000). Several newspapers were delivered to his childhood home daily. Each morning’s news was discussed over each night’s dinner table.

Purdy wrote for his high school newspaper and played sports. He was good enough to make the teams as backup quarterback or third-string guard, but his feet never saw much field or court. After his junior year, Purdy recalls the sports editor of his hometown paper, the Celina Daily Standard, telling him, “I’ve seen you write. I’ve seen you play. You write a lot better than you play.” He quit playing sports and began making 15 bucks per story that year in 1969.

Nearly 11 years later, in 1980, Purdy would hear Al Michaels ask at the end of the U.S.-Soviet Union Olympic hockey game, “Do you believe in miracles? Yes!” Seven years after that, he would find himself in the presence of the Prime Minister of Australia and Jimmy Buffett at the 1987 America’s Cup. Back then, moments like these were more common.

Wife of the year

Purdy is a young sports writer in Dayton, Ohio in the early seventies. He sits in the dining hall at Miami University interviewing football coach Dick Crum. Crum tells Purdy that, until now, newspapers didn’t give his team much attention. “What’s changed?” he asks. Purdy replies that the team is better this year; what he won’t reveal is that one of his sister’s roommates down the street is a blonde girl named Barb, and she will become his wife.

Now he calls her “Wife of the Year every year,” and they will be married four decades in August. Outside of vacations, they’ve probably spent less than a hundred weekends together in total, Purdy says. “She deserves more of my time.”

In the beginning of their marriage, Barb tried to read all of her husband’s work. Now, she says, she doesn’t. “I sometimes think that sports consumes our life,” she says, but she’s also come to realize that it’s her husband’s job. What frustrates her is that she knows he feels like he’s always behind.

Purdy remembers his early years at the Dayton Journal Herald, then the Los Angeles Times and, after that, the Cincinnati Enquirer. Back then, he produced one story a day, which would appear in the paper the next morning, and probably be forgotten by the following afternoon. At night he would put his head on his pillow knowing that he had accomplished his goal, or, if not, would do better next time.

On nights these days, he lays his head on his pillow and second guesses himself. “I have yet to find a rhythm that makes me feel comfortable. It kind of makes me feel restless, restless and confused all the time.”

When Howie met Purdy

It’s the early 2000s. Bruce Springsteen is playing a concert at the SAP Center in San Jose. Beforehand, Purdy hosts a get-together at his house. In attendance are Purdy’s colleague, Dan Brown, and Brown’s friend and fellow sports writer Howard Beck. They gather in Purdy’s backyard, for hamburgers and beer.

Purdy grew up reading the greats, the New York Times’ Red Smith and Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times, among them. Beck, now a senior writer at Bleacher Report, grew up reading Purdy. “Mark Purdy had been my sports writing idol as a kid,” says Beck, raised in San Jose.

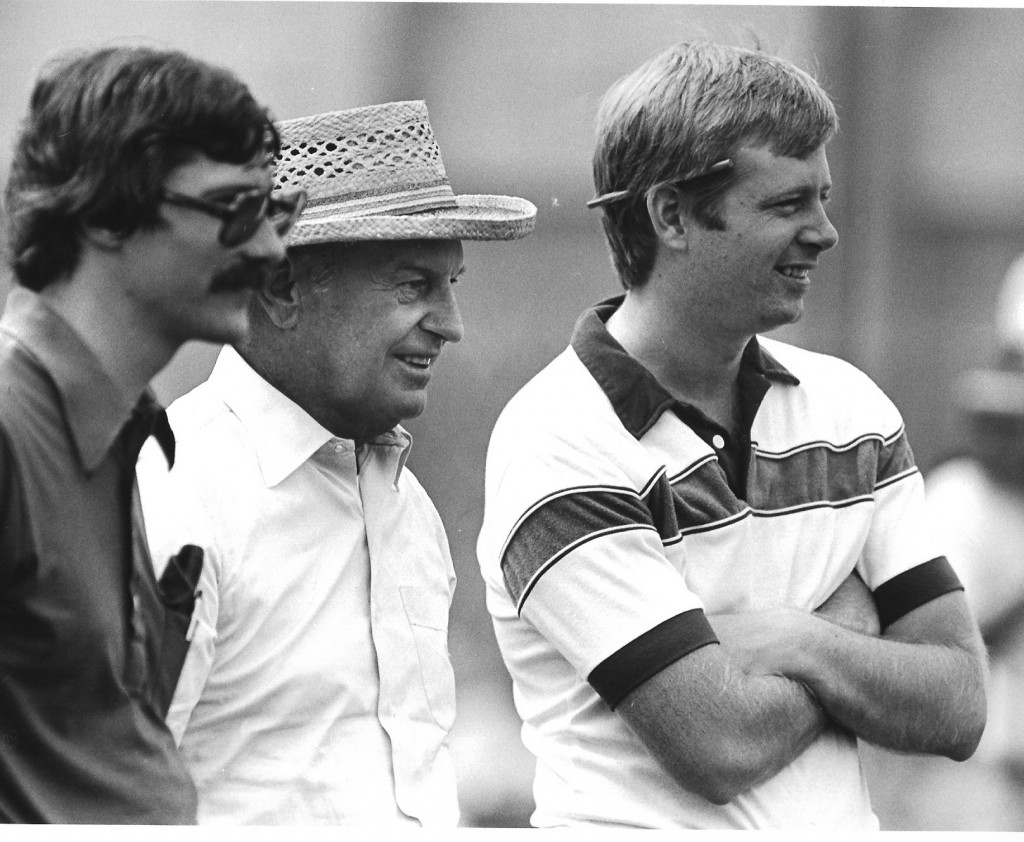

(Photo courtesy of Mark Purdy)

Beck met Purdy in the late eighties or early nineties when they were both working in the 49ers press box at Candlestick Park. They stood in line at a buffet when Beck sheepishly introduced himself. But this wasn’t the introduction that would go down in Dan Brown’s history.

Beck took another moment before the concert to praise Purdy. According to Brown, Purdy was trying equally hard to make Beck stop talking.

Beck had hired Brown at the University of California, Davis college newspaper years before, and Brown said he “spoke the gospel of Mark Purdy” back then. “Introducing him to Purdy was like taking a teenage girl to meet The Beatles.”

“At that point there’s probably less of the wide-eyedness for me,” Beck recalls, “but you never really completely divest yourself of the 15-year-old in your head. And the 15-year-old in my head was sitting there like, ‘This is surreal.’”

Beck remembers the essence of Purdy’s response: I always tell younger writers in the business to just be good to the people who come behind you.

“I’ve always remembered that,” Beck says, “especially every time some young punk is coming up and telling me they grew up reading me.”

Brown, who has worked with Purdy at the Mercury News for nearly 21 years, says Purdy doesn’t write his columns as much as “he crafts them.” Brown, too, admits that he’s still always somewhat aware when he’s talking to Mark Purdy, “sportswriting superhero.”

Bust the deadline

The press box is racing. A big game comes to an end, and writers work furiously to file their stories on time. Keyboards clack and focus takes no commercial breaks.

Dan Brown looks over to Purdy’s screen. On it he sees a Bob Dylan video or an article on the top 25 rock records of all time. This is the way Purdy works.

Tim Kawakami, Purdy’s fellow columnist at the Mercury News, says, “He’s quite unique – when we’re all writing, he’ll be looking at videos, scrolling through different websites, wondering if I want to look at this weird story about some subject that is not at all related to, say, the 49ers game we just watched.”

“It’s not procrastinating. I think he’s just trying to get in his world,” Brown says. Purdy’s advice is to “bust the deadline whenever you can.”

“You shouldn’t teach his process to children,” Brown says with a laugh.

Purdy remembers the 1991 Pan American Games in Cuba. There was a long line to enter, of all things, the bowling competition. “I’m not an idiot; I know a good story when I see one,” Purdy says. He and his two colleagues entered and were told where to sit.

Ten minutes before the game started, the usher approached them and apologized – they were going to have to move. One of Purdy’s friends tried to negotiate with the usher. The other got mad, insisting that they were going to stay in their seats. “And I’m going, ‘Let’s just try to calm down. We’re here at a freaking bowling alley,’” Purdy says.

Just then, applause erupted in the stands, flashbulbs popped, and Cuban President Fidel Castro approached Purdy’s spot. “Well, I got my column!” Purdy said. It was published on Aug. 13, 1991 and began, “Monday, however, Fidel really topped himself. Monday, he took my seat.”

Of this moment, Purdy says, “Unlike those days where you’re like, ‘Should I be doing this?’ you’re like ‘Yeah, I got this. This is exactly where I should be today and this is exactly what I should be writing about.’ That’s what makes it. That’s what makes it.”

Purdy continues to sip his hot chocolate. He looks back on moments like these – some of the greatest he’s experienced as a sports writer – and tries to think of more recent examples. The excitement dwindles in his voice and his knuckles stop pounding the table with excited emphasis, as he half-heartedly lists last year’s Game Seven of the NBA playoffs and the Sharks’ run for the Stanley Cup. It just isn’t the same.

With a laugh, he says, “Maybe I shouldn’t quit.”