“Nobody saw this year coming,” reports Steve Tobak, a resident of Scotts Valley for 23 years in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Tobak has endured “massive landslides, road outages… everywhere from [his] own private road where [he’s] been blocked in and lost power for five days at a time, to Highway 17, the main freeway in and out of Santa Cruz, which has been out for several days. Traffic has been a nightmare.”

As Tobak explained, this past winter in California was nothing short of exceptional. At least fifty feet of snow above 8,000-feet in Squaw Valley, according to the resort’s weather stations, caused several major closures of I-80 over the Donner Pass. In February, 177,000 people were evacuated from the Oroville Dam area near Sacramento after emergency spillways failed. The worst flood in decades occurred in February in San Jose when Coyote Creek overflowed, due to a failure in the Anderson Reservoir spillway.

The damage of the extreme weather is difficult to estimate, but Santa Cruz County puts its damage to local roads alone at $70 million in the last three months, according to director of public works John Presleigh, who spoke to the Santa Cruz Sentinel in March.

Santa Cruz County’s Department of Public Works has turned the data on compromised roads, landslides and detours into an interactive map so that its citizens can stay informed and plan ahead.

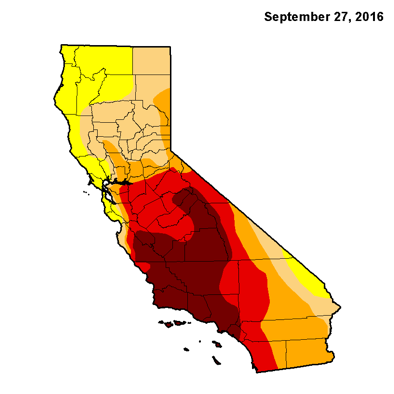

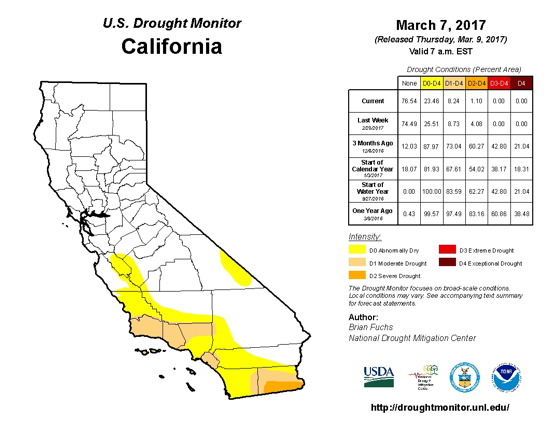

Just a bit more than six months ago at the start of the recorded water year, 62.27 percent of California was at somewhere between severe to exceptional drought status according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, maintained by the National Drought Mitigation Center. One wet winter later, just 1.1 percent of the state qualified for this drought status. On April 7, Gov. Jerry Brown declared the end of the drought state of emergency in most of the state.

Though it appears California’s drought is mostly over, the destruction of homes and property is a high price to pay for the recovery. Climate scientists say it’s not as simple as one wet winter leveling the score with five dry years, and the extreme swing from dry to wet is a preview of California’s future as its climate changes.

Noah Diffenbaugh is a professor in the Stanford School of Earth, Energy and Environmental Sciences and a senior fellow in Stanford’s Woods Institute for the Environment, and he specializes in climate science and its impact on living things. (EDITOR’S NOTE: Peninsula Press is a project of the Stanford Journalism Program in the School of Humanities and Sciences.) “California’s climate is variable, and we get swings from wet to dry just in the baseline,” Diffenbaugh said, but the variation this winter is different from the swings we have seen over the past hundred years.

“The warming climate increases the odds of what we’re having now,” Diffenbaugh said. “Our water system is built around snow. Normally, about 30 percent of our water supply is dependent upon snow pack, but a warming climate will cause snow to melt earlier in the year. Warmer storms produce relatively more precipitation at lower elevations compared to snow. Both of those increase the runoff that then increases the water that goes into our dams and reservoirs.”

The fact climate change makes these extreme events more likely in California means the state must rethink its water infrastructure in order to plan for the next 10, 50 and 100 years.

“It’s clear that our water system was designed and built in an old climate,” Diffenbaugh said. “The snowpack is less reliable now than it was back then, so we’re not going to get the same natural reservoir, not the same natural storage, not the same natural flood control that our water system was built around in terms of snowpack. We’re also much more likely to have hot, dry periods which creates a water deficit and pushes the system.”

To minimize the impact of this new normal, California’s infrastructure has to catch up to technology that works to take advantage of rainwater when it is plentiful. One technique to do so is groundwater recharge, which involves controlled flooding of fields with excess runoff, in order to replenish underground wells that are depleted in times of drought.

“Groundwater recharge will both allow us to store water and replenish groundwater that has been extracted, and to relieve pressure on dams and reservoirs in terms of flood control. That’s a win-win,” Diffenbaugh said. “In terms of ways to increase water supply, it’s been shown that groundwater recharge is quite cost effective.”

For local resident Tobak, the extreme weather forced his personal values sharply back into focus and made him consider the other natural events to which he is subject. “I certainly hope that we don’t end up with extremes like this over and over again. But you know, when you live here in the mountains, we’re well aware of our situation. There is no guarantee.”