Gina Cooper fiddles with the square gold ring on her left pinkie while recounting her and her son’s experience with homelessness. She sits in the day center of Home & Hope, a shelter that supports four to five homeless families at a time in the Bay Area. For five months, this ivory-painted center was the only place Cooper could shower and do laundry. Now, it is her office, where she works as Home & Hope’s program manager.

Cooper’s story is one with a happy ending, but her guilt about having once fallen into homelessness remains. She pauses, blinking back tears, before saying, “It was our little secret. Our lives were reduced to homelessness, and I felt responsible. I felt 100 percent responsible.”

It was our little secret. Our lives were reduced to homelessness, and I felt responsible. I felt 100 percent responsible.

In 2012, Cooper and her son, Dante Walton, then 12, lived in a small apartment in Belmont, California, with Cooper’s mother, Margie Cooper. Though Gina Cooper was only making $9 an hour working as a cashier at Belmont’s Goodwill, her income, combined with Margie’s, helped the small family make ends meet.

But on March 12, 2012, Margie drove herself to the doctor and returned with a cancer diagnosis. She told Cooper and Walton that evening; Cooper arranged to take off work for her mother’s first appointment later that month. On March 21, 2012, before they could attend that appointment, Margie passed away.

On that day, Cooper lost many things — her mother, the emotional stability she had come to rely upon since becoming a single mother, and Margie’s income. Walton, too, lost his Mimi, who had taught him how to cook while his mom worked long hours. But as residents of increasingly affluent San Mateo County, grief became a luxury they could literally not afford.

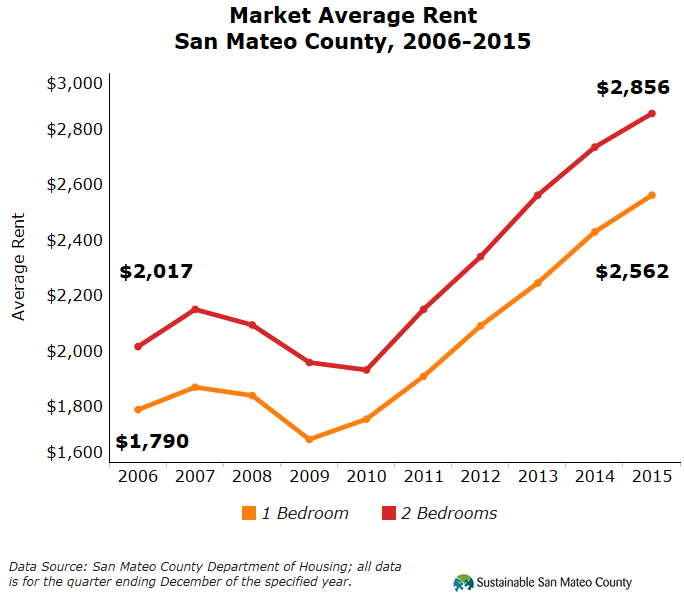

The cost of living in Northern California was rising quickly, especially in San Mateo County. The county’s rental costs were tied with San Francisco’s and Marin’s as the highest in the country, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Cooper’s income wasn’t enough to cover her and Walton’s needs, and they were soon evicted from their Belmont apartment. For three months, they slept on the couches of nearby friends. However, these friends were also struggling; feeding and housing Cooper and Walton grew too heavy a burden.

Having exhausted her support system , Cooper and Walton became homeless. They joined roughly 150 families in San Mateo County living without a home, seeking aid from shelters and nonprofits. Everywhere they went, they found crowded shelters with long waiting lists. Often, they did not qualify for aid because Cooper still held a job.

Eventually, they heard about Home & Hope at a church Cooper and Walton tried to attend as regularly as possible. In the five months they spent with Home & Hope, Cooper and Walton slept in an E-Z UP tent set up in a church for a week at a time. At the end of that week on Sunday between 2:00 p.m. and 3:30 p.m., they, along with the other four families living with Home & Hope, moved to another of the program’s 16 host congregations. Though Cooper and Walton now had a guaranteed place to sleep each night, the experience remained frustrating for both of them.

“He went from a warm bed in a home to a cot in a tent,” Cooper recounted softly.

During the five months they slept on a cot in a tent, Cooper worked overtime at Goodwill to cover the $200 “optional” team and equipment fees of Walton’s school football team.

During those five months, Cooper worked until 9 p.m. nightly while Walton did his homework in Margie’s 1996 Cadillac DeVille by the yellowish glow of the interior car light.

During those five months, they woke up in their tent at 6 a.m. every day, including weekends, to eat the church-provided breakfast, pack brown bag lunches for the day, head to the Home & Hope’s day shelter to shower and hide evidence of their homelessness, and then get Walton to school by 8 a.m.

During those five months, Walton became one of 527,000 homeless students in the United States, and he often cried on the drive to eighth grade, saying before he slumped from the car: “I hate this.”

During those five months, Walton, with his big build and brown skin, was told he was not performing well enough in school. Cooper assured his principal that nothing serious was going on at home.

During those five months, Cooper sat as far away as possible from the other football moms on the bleachers, afraid she might reveal something embarrassing about not only her own homelessness but her son’s.

But also during those five months, she and Walton listened on the radio as the San Francisco Giants won the 2012 World Series against the Detroit Tigers. They cheered with fellow Giants fans/volunteers they had just met that night.

During those five months, they merrily celebrated Christmas in the Jewish temple, Peninsula Temple Beth El. The volunteers and four other homeless families made and ate gingerbread cookies, decorated a Christmas tree and opened presents from Santa.

During those five months, Cooper and Walton lived together, fell asleep together and kept their secret together.

He went from a warm bed in a home to a cot in a tent.

Because food, laundry, computers, showers, soap and other necessities were provided at Home & Hope, Cooper eventually saved up enough money to rent an apartment in San Carlos. There, she and Walton draped a San Francisco Giants blanket on the bottom of the queen-sized bed and bought a potted plant for the backyard.

Two months after living self-sufficiently, Cooper took a chance on a part-time job with Soil Engineering Construction. A year later, in April of 2014, she lost that job and immediately visited Home & Hope, the only place she felt comfortable discussing her growing fear of becoming homeless again. There, she talked with friend and then executive director of Home & Hope, Raj Rambob. She came seeking only a shoulder to cry on but left with a new job, as program assistant for Home & Hope.

Now promoted to program manger, Cooper spends her days recruiting volunteers and fundraising for the 15 families on Home & Hope’s waitlist. Since starting work at the shelter, she and Executive Director Meg Clark have seen more families coming from “middle-class income levels,” rather than “more traditional poverty levels.” Most Home & Hope families work two or three minimum-wage jobs, but it would take about four minimum-wage jobs to support a family of four in San Mateo County. Though facing an uphill battle, Cooper is happy to be giving back to the community that loved and supported her and her son.

Walton, too, never forgets how much others helped him and his mother. At age 15, he spoke to the seventh graders at Peninsula Beth El, where he celebrated Christmas while with Home & Hope, about his experience being homeless. He has developed what Cooper calls “a heart for helping” and taught himself how to make skateboards for kids who cannot afford their own. He also carries on his grandmother’s love of cooking for family, often making dinner for Cooper and himself.

Back in Home & Hope’s day center, Cooper fiddles with her ring again as she tells one final story.

Thinking about her homelessness in 2012 reminds her of how carefully she had to watch the gas tank in her mom’s Cadillac. The car would always make obnoxious noises when the tank neared “Empty.” That happened often in 2012, with gas prices averaging $4.67 in Belmont. Then last year, as she was driving to Home & Hope, Cooper jumped at a noise her car had not made in four years. But this time, her tank neared “Empty,” not because she had no other option, but simply because she’d been too busy with work to fill up. Tears came to her eyes, she says, as she whispered a quiet thanks and drove to the gas station.