In the basement of Stanford’s Jen-Hsun Huang Engineering Center, through double bamboo doors, nearly 160 eyes are fixed on an auditorium screen, primed to see Adam Boies’ magic. The seasoned mechanical engineer, mic clipped to his chest, finishes a sentence and pivots toward the slides. Onscreen, a video shows tiny filaments of pure carbon—called carbon nanotubes—transform themselves from a conglomerated mess to a series of perfectly aligned geometric beauties, thanks to the introduction of an acid. The nanotubes’ movements are so intentional, they seem conscious. A moment of shared awe settles across the room.

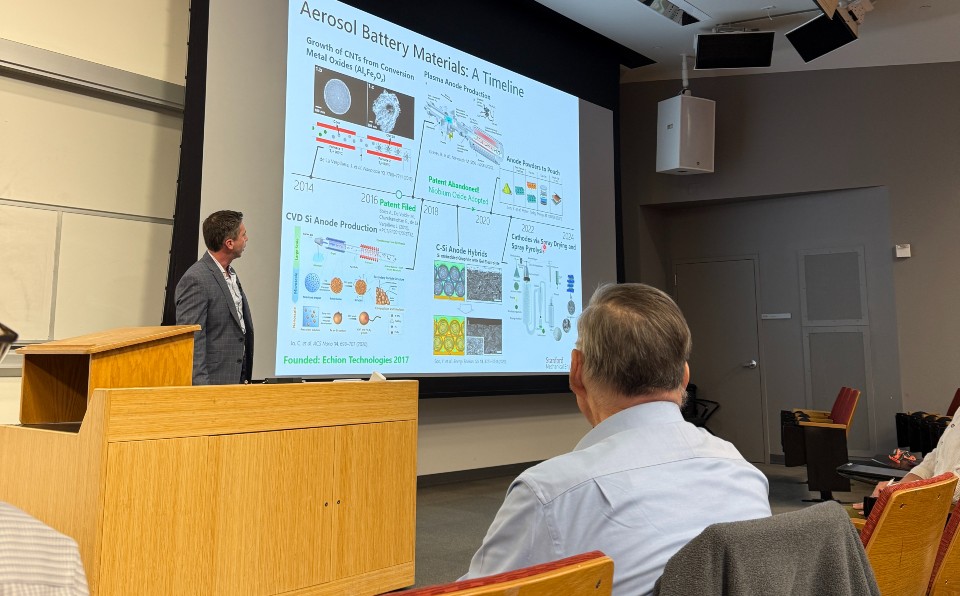

It’s a Monday afternoon, and Boies is presenting at the Stanford Energy Seminar — a 20-year-old speaker series beloved by students and faculty alike—about the work his lab does. His talk is titled “Can Innovations Scale? Production at the Materials-Energy Nexus.” This talk too is a nexus: of professors, startup CEOs and undergraduate and graduate students spanning myriad disciplines, all curious about Boies’ work.

His envirotech research asks questions that tug at the borders of structural and chemical engineering as well as new ways to counteract climate change. Can we convert carbon emissions from fossil fuels into useful materials for building large structures? Boies emphasizes that the answer will require a two-part solution: not just materials that can encase climate-damaging carbon in the very structure of our roads and buildings, but ones that are as inexpensive and easy to use as the asphalt, steel and concrete currently dominating construction.

“We’re seeking to make carbon a resource for, ultimately, the built environment,” he explained, the built environment being the human-made surroundings where we live and work. Through the serendipity of physics, carbon nanotubes are stronger than steel, are lighter than concrete, conduct electricity better than copper, and can bend without breaking. And through the hard work of Boies’ lab, they are now easier to produce, align and shape into strong, lightweight materials that could one day replace traditional materials in major structures—and keep the carbon they are made of out of the atmosphere for the life of the material.

Anders Luffman, in his third year as a Stanford BS and MS candidate, attended the lecture because he’s enrolled in its accompanying class. “CEE301: The Stanford Energy Seminar” offers “a lay of the landscape in energy” for Luffman, useful for both his Energy Science and Engineering undergraduate and his Management Science and Engineering graduate programs.

John Weyant, in his forty-eighth year at Stanford, is similarly energized by the Energy Seminar. He is a Professor of Management Science and Engineering and a Senior Fellow of the Precourt Institute for Energy—the seminar’s sponsor. For Weyant, Boies is special for “working not only on the basic science, as he put it, in the test tube, but the scale: being able to scale up those processes so they’ll actually make a big difference in terms of reducing our dependence on carbon and carbon-based fuels.”

Just as Boies was exiting the auditorium, surrounded by a flurry of teaching assistants, lab members, and undergraduates, we posed him one last question: why give a talk like this? Why take time away from the lab to be here? “You know, really it is just meeting people, like you! And people that don’t come to engineering lectures, right?” he answered, continuing, “it’s being able to speak to a broader audience. You write an article and then somebody reads your article and they ask me questions.” Human connection is how ideas transform from conglomerated messes to perfectly aligned geometric beauties—and in the search for climate solutions, that might be the most important magic of it all.