The Navy is struggling to retain its top fighter pilots due to low pay, extended deployments and fiercer competition for their skills from the commercial airlines.

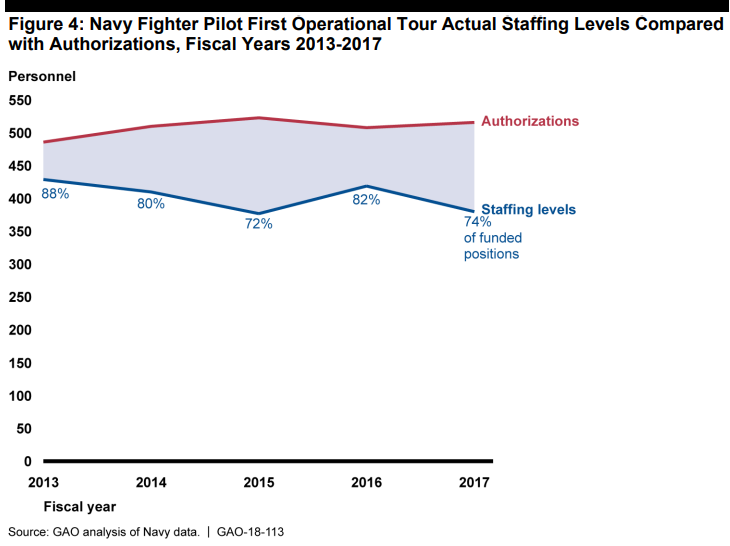

Through creative accounting and by shuffling personnel around, the Navy has been able to achieve their retention goals on paper. But for a decade the Navy has had only half the fighter pilots it hoped to retain.

According to the Government Accountability Office, Navy officials define a shortage as being unable to “fully staff deploying squadrons,” or having enough pilots to operate aircraft onboard carriers out at sea.

For now, the Navy still has the personnel to staff an increasing number of deployments. In October, the U.S. sent two carrier strike groups to the Middle East. They have done so while maintaining the same operational tempo and carrier posture in every major body of water as they did during the ‘War on Terror,’ which ended over two years ago.

The Navy manages to get by with pilot shortages by extending and forcing back-to-back deployments and asking those on non-deployable “shore tours” to work more shifts.

The Navy has also leaned more heavily on reserve pilots to fill gaps in staffing. These reserve units are mostly comprised of pilots who recently left the service, took a job flying for the commercial airlines, and when asked to do so, put on a Navy uniform to train new jet pilots.

Several current and former military members spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of retribution in a small aviation community that includes active-duty, reservists and commercial airline pilots.

Military pilots and experts say this isn’t sustainable, and that readiness will decrease unless the Navy makes changes.

“You can’t do this job well without giving either your health or your relationships or something else. They ask for more every year with less and less people and resources,” said a Lieutenant Commander fighter pilot who shared that their passion and commitment to the Navy almost ended their marriage. Two years ago, they were staying in naval aviation forever. But after a deployment that was scheduled for five months was extended to nearly ten months, they requested to resign.

Commander Kristen Hansen serves as the commanding officer of VFA-122, a squadron that trains new pilots for carrier operations. Her unit is operating with 50% of its pilots at any given time, resulting in longer workdays.

“After you’ve given a decade plus to the Navy, at some point, you and your family have to come first too…You can totally say ‘for God & Country,’ but that goes only so far when you have, you know, people at home that are constantly having to watch you go away,” said Hansen.

U.S. Navy/Defense Visual Information Distribution Service)

An instructor pilot stationed in Lemoore, CA, who plans to resign from active-duty for an airline job, has worked so many extra hours that he said, “I did the math and I make less per hour than most Chick-fil-A employees.”

Another said he was sent on 40 missions away from home, resulting in “being gone 15-20 days out of the month during the time I was supposed to be ‘resting and recovering’ from increased deployments.”

Hansen explained this as an accordion effect. The Navy shuffles pilots into squadrons that will deploy, meeting their retention requirements, while the other squadrons “definitely do more with less.”

Vice Admiral Robert Burke, chief of Naval Personnel from 2018-2019, testified before the Congressional Subcommittee on Military Personnel in July 2019 that, “While mid-level officer retention represents our greatest challenge, resignations have also increased among junior and senior aviators due, in part, to intense competition from private industry.” He cited this trend beginning since 2009.

The 2019 Department of Defense Report to Congress acknowledged that a global supply and demand imbalance for commercial pilots means the airlines are hiring at increased rates. While the military estimates needing more than 75,000 pilots in the next 20 years, commercial airlines will need to hire 206,000 over the same period.

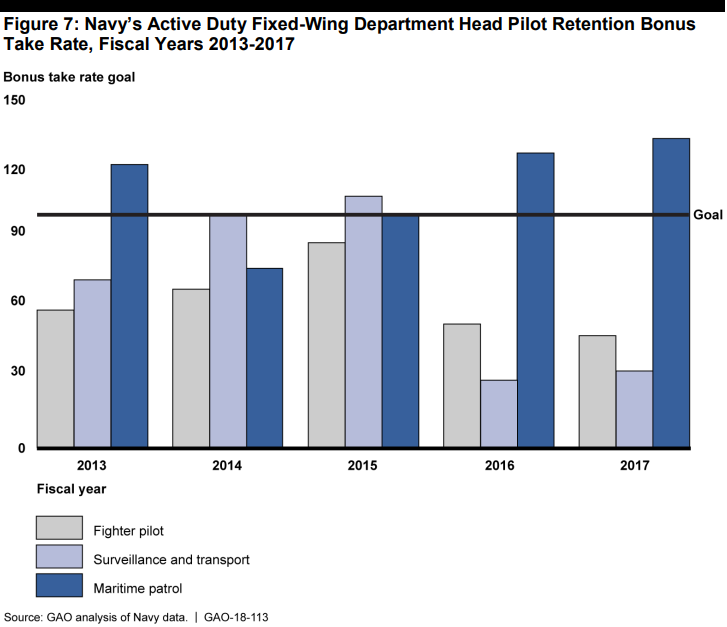

The Navy jet bonus for fiscal year 2023 is $35,000/year before taxes and requires an additional five to seven years of service, an amount pilots say is inadequate to convince them to stay.

“The bonus pay is a laughable sum,” said a Navy pilot who is contemplating taking a job as a commercial airline pilot next year, which he says will allow him to make three times the pay with better quality of life. No more long hours without additional compensation, long deployments, unpredictable schedules, being asked to fill roles that are above pay grade, not taking care of his health, and most importantly, not spending time with his family.

A fighter pilot who departs naval aviation after 10 years of service would start as a First Officer for a commercial company. At United Airlines that salary is approximately $109,000 per year. Based on their Navy training and capabilities, they can promote to Captain within a year and earn $312,000 or more annually. A Navy jet pilot stationed in Lemoore with 10 years of service makes $104,000.

Each pilot shared the same love and passion for flying jets. The TOPGUN pilots reveled in being at the peak of their tactical prowess and fulfilling childhood dreams. Yet, many stories ended the same – “burn out.”

“I enjoyed it being my whole life and letting everything else kind of fall by the wayside. I am getting out after this tour because I am incredibly burned out and four [deployments] in two years, isn’t going to help,” said a Lieutenant Commander approaching her end of contract who is currently onboard a carrier out at sea.