Robbie Tenerowicz-Byrd isn’t a smoker, he’s an infielder. His summer nights are supposed to be spent covering second base, not restocking the athletic gear section during the overnight shift at the Bellevue Walmart outside of Seattle.

But for Tenerowicz-Byrd, a 26-year-old minor league baseball player in the Cincinnati Reds organization, that shift was his reality three months into the COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns in the spring of 2020.

“In June, July, and early August, there was nothing better than a 3 a.m. cigarette,” he said.

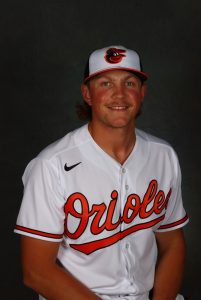

He was not the only one in uncharted waters. Last July, Baltimore Orioles minor league pitcher Griffin McLarty, 22, found himself mostly planted on his childhood couch in Louisville. He and his younger brother Gavin, a senior pitcher at Oldham County High School in nearby Buckner, Kentucky, played catch to stay loose. For about a month and a half, the elder McLarty brother also bussed tables at Barn8, a nearby horse farm with a restaurant and bourbon bar. He had a great view of horses training at their facility while he wasn’t allowed to train at his.

“I think it’s confusing for a lot of people,” McLarty said. “If I tell them that I play for the Orioles, most people will kind of give me a half-second hesitation, like ‘Okay, then why are you here?’”

For a sport that emphasizes routine and repetition on the field, it is surprising how little certainty professional baseball players feel away from it. Unlike the NBA and NFL, where the best players see the premier roster immediately after the draft, in baseball the vast majority of MLB draft picks spend significant time in the minors, where most careers end. Last December, when MLB announced a reorganization of Minor League Baseball that cut the total number of affiliated teams from 163 to 120, the available opportunities shrunk even further. The 43 teams left out represent a little more than 1,000 roster spots lost.

Low wages (a minimum of $500 a week for players in A-ball, or about $10,500 per season), unstable location requirements (players can be traded or reassigned to different teams without notice) and bus travel to small towns across America are constant reminders of how far players are from the glamour of the big leagues.

In early March 2020, when the pandemic first took hold, the little certainty that remained was wiped away. Each of the 5,000 or so professional baseball players across the nation has a different pandemic story. McLarty remembers being in his hotel when he started seeing messages that everything was shutting down.

“There was so much buzz circulating and no one could focus on the task at hand,” he said. “Then we finish the day, go to the hotel, and get an email that night saying ‘Hey, don’t show up tomorrow.’”

For Jesse Franklin, 22, an outfielder selected in the third round by the Atlanta Braves, the really strange part of the pandemic set in after the draft in early June.

“No one could understand why I was still at home, instead of joining the Braves,” Franklin said.

He took online political science classes towards a degree from the University of Michigan while at home in Seattle before attending the Braves alternate site camp, or “taxi squad,” in July. He considers himself one of the lucky ones.

“I got 100 to 150 at-bats between the ‘taxi squad’ and ‘instructs,’ which I’m really thankful for because there’s a lot of guys that didn’t get anything this summer,” Franklin said.

Tenerowicz-Byrd might have had the most uncertain summer of all. On June 1, he received a call from his former organization, the Tampa Bay Rays, telling him that he had been released. At the time, he was working with coaches at Driveline, a sports-performance facility near Seattle. Soon, rent and training costs were due.

From June through August, Tenerowicz-Byrd’s schedule looked a bit different than his usual summer. Hit from noon to 3 p.m. Lift from 3:30 to 5 p.m. Nap until 9:30 p.m., when he had to hop in the car for work. Walmart shift from 10 p.m..to 7 a.m. Another nap, rinse and repeat.

“There I am picking up 45-pound weights at three in the morning thinking, ‘This is not what I want to be doing right now,’” Tenerowicz-Byrd said. Before signing with the Reds on December 14, he considered playing in Japan.

Still, he says, he felt his situation could have been worse. “I just stay focused with what I do,” he said. “I had a gap year basically to get better. It was the best thing that could’ve happened to my baseball career in my life.”

For now, though, the best thing for all these players will be to return to the field. Their parent clubs, the major league teams, would like that as well.

As Oakland Athletics President Dave Kaval said, “COVID created a very challenging situation for the pace of development. That’s why we’re hopeful that we can get beyond the pandemic, so we can get the young, talented baseball players back on their way to fulfilling their dreams.”

Spring training for the Major Leaguers has begun, and the Minor League camps will open in the coming weeks.

Tenerowicz-Byrd has no doubt that he’ll be ready to go. He’s been preparing for seasons for as long as he can remember.

“My mom has photos of me in my diaper with a glove on,” he said. “I always knew it was what I wanted to do.”