A waxing gibbous occupied the night sky, providing two skippers just enough visibility to sail without lights. The third boat, was lit up and sailed directly in front of the Coast Guard. As patrol took notice of the obvious vessel, the other two boats, slipped into an alternate route and approached the island from behind.

Members of varying tribes drove from around the Bay Area to meet in Sausalito and prepared for their short, yet historic voyage. Although their destination was an abandoned prison without provisions or proper bedding, they packed sparingly and moved quickly. All 89 soon-to-be occupiers and their food and supplies fit onto two sailboats. Using the third sail boat as a decoy, they embarked in the early hours of the night to reclaim Alcatraz.

It has been 50 years since the 1969 occupation of Alcatraz, a historical 19-month long protest that fueled indigenous activism around the country and inspired legislative changes that still benefit Native Americans today.

The Bay Area is coming together to celebrate the occupation and pay homage to those who fought — and continue to fight — for indigenous rights. Four days of events are scheduled on the island, starting Nov. 20, with smaller pop-outs around the Bay that will run for 19-months (the length of the original occupation). Activities will include prayers, musical performances and talks by the original occupiers.

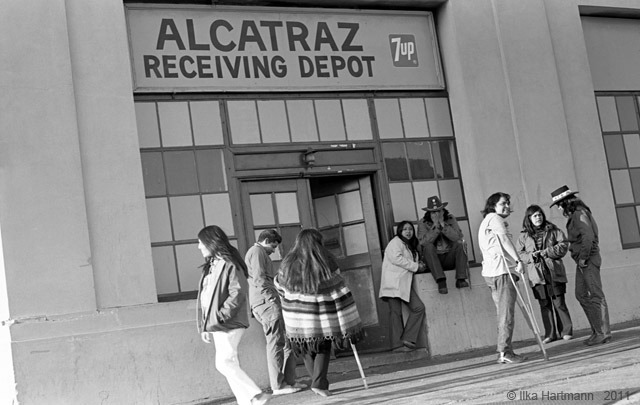

On Nov. 23, the public exhibit Red Power on Alcatraz: Perspectives 50 Years Later opens. The exhibit will feature photography from the occupation by Ilka Hartmann and Stephen Shames, as well as original materials from the collection of Kent Blansett and contributions from the community of veteran occupiers.

“I am so proud to be included,” Ilka Hartmann said. “I remember the support in the Bay Area at the time was enormous…it was very intense.” Hartmann’s experience covering the occupation is a story in itself: She arrived on the island by chance, shot with cameras she had never used before, became renowned as a result of the pictures she made, and developed lifelong friendships with many of the occupiers.

Although Hartmann is German, she says that the Native Americans always made her feel welcome and often greeted her camera with a “peace sign,” which was “a sign of the times that we were from the same ilk.” In large part, Hartmann’s photos became the visual record of the occupation and have been featured in countless books and exhibits.

According to past occupiers, they hoped to convert the island into a cultural center and due to a 1868 treaty they claimed, surplus (or abandoned) federal land belonged to them. Because the government rejected this claim, the protesters felt it was their duty to take the island back.

The Indian Termination Act of 1953 also motivated the uprising. The act devastated many Native American communities by stripping them of federal recognition, a move that allowed for their land to be bought and sold without their consent.

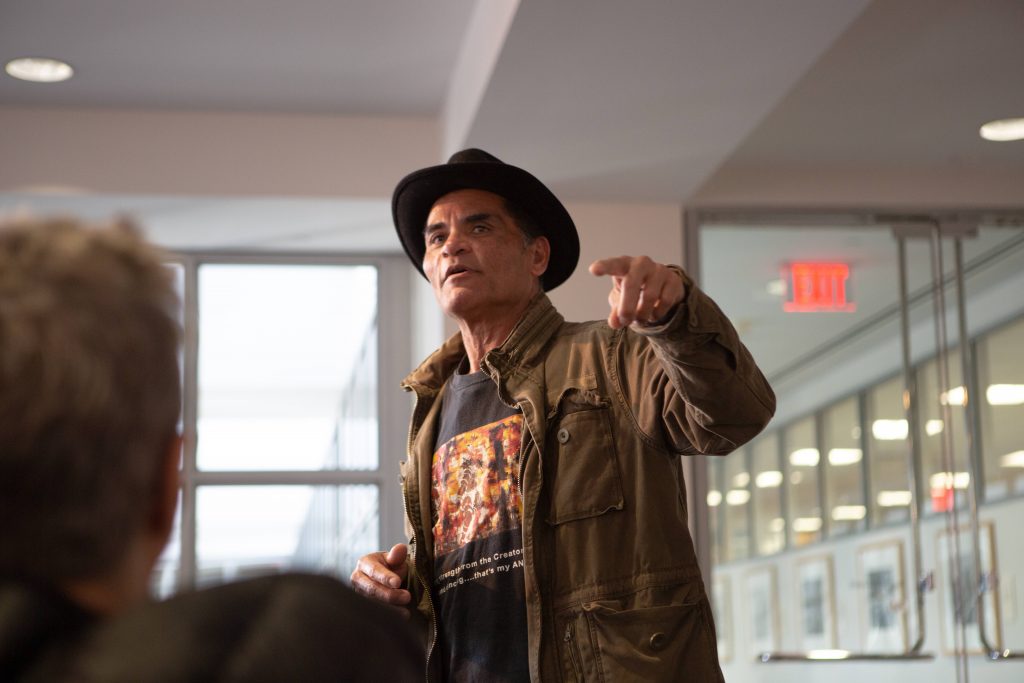

“Imagine someone coming to your home to tell you that you that your land had been sold. You could either leave or they would make you leave,” said Eloy Martinez, one of the oldest living protesters, who is now 78 years old.

The occupation brought tribes from around the country together and elevated their voices to a national stage.

“At the time Indians were the only group that didn’t have a voice…there were the Black Panthers, Cesar Chavez’s Farm Workers, and Asian groups, but nothing for Indians,” said Martinez. “The fact that there was no water or electricity on the island symbolized what it was like for us on the reservation.”

At age eight, Alan Harrison sailed to Alcatraz. His mother Luwana Quitiquit, a student activist from UC Berkeley moved him and his two siblings to the island to include them in the movement.

“At first we were just kids running around. For kicks we would go look in the dungeon, fish for crabs and climb into the lighthouse to watch the big light go around,” said Harrison. Although young, he remembers the upbeat energy and communal lifestyle.

“We would cook Indian soup for dinner and eat and play drums together,” Harrison recounted.

Press and visitors were a regular part of life, one that the occupiers knew were vital to spreading their message. Once, Harrison was playing basketball when a helicopter landed on a slab of concrete next to him. It was Dan Rather and his news crew. Rather dismounted and “nervously approached me for an interview,” said Harrison with a laugh. After the brief mid-court interview, Rather boarded the helicopter and flew into the horizon.

After 19 months President Richard Nixon ended the occupation by sending a government officer to remove the remaining protesters. And while Nixon did not convert the prison into a cultural center he did sign 52 legislative measures that benefit Native Americans. Among the most impactful, were the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, which increased autonomy and granted sovereignty to Native Americans on their land.

“Indians empowered themselves when they left, and that is deep,” Harrison said, as he choked up and held back tears. After Alcatraz, “Red Power” spread nationally. Like-minded protests and new occupations emerged at historic sites such as Plymouth Rock, Mount Rushmore and the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The last living occupiers and a new generation of allies hope that this year’s celebration will continue to inspire activism in their community and encourage the National Park Service to establish a museum on the island dedicated to Native Americans.

“I still love my country,” said Harrison. “And I am a patriot, but exploiting people isn’t right, and that’s what Alcatraz was about.”

Editor’s Note: This story has been change to correct the description of the night of November 20, 1969, the beginning of a 19-month long protest on Alcatraz.