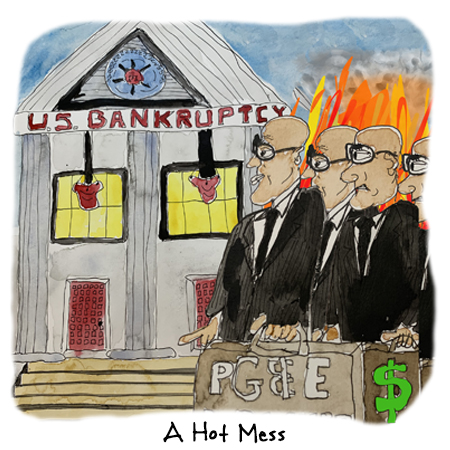

Autumn brought PG&E unprecedented power outages, wildfires, and massive forced evacuations, problems that would strain any utility. But for PG&E there was an additional challenge: it had to do so while undergoing the largest bankruptcy of a public utility in history.

In September, U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Dennis Montali complicated PG&E’s path to reorganization by authorizing creditors to propose a rival plan of reorganization that would, if approved by the court, allow them to take control of the company. The rival plan was not only an existential threat to PG&E’s management, but it complicated the company’s ability to meet a June 30, 2020 deadline to participate in a multi-billion fund for new wildfire claims created by the State of California.

And in early October, the hot crackle of fire season in northern California arrived, with heavy winds predicted. These were roughly the same conditions that led to massive deadly wildfires in prior years, most disastrously the Camp Fire in 2018 when the town of Paradise was incinerated, and more than 80 people were killed. Sparks from PG&E equipment, blown into the crispy tinder of climate-changed vegetation, were blamed.

PG&E hoped to avoid a new round of wildfire claims in 2019 by preemptively turning off power in high risk areas when high winds threatened. But on October 9, when PG&E implemented the Public Safety Power Shutoffs, as the power outages were called, almost a million homes were “de-energized.” In the hot light of public scrutiny that followed, PG&E’s planning and execution were excoriated. California’s Governor Gavin Newsom accused PG&E of “greed and mismanagement.”

And there were fires anyway.

The Kincade Fire blazed up in Geyserville on October 23 and in the first week burned nearly 80,000 acres and forced the evacuation of 180,000 people from Sonoma and Napa counties, according to the Sonoma County Sherriff’s Office. Early information released by PG&E suggested the possibility that the fire was caused by a downed transmission line.

The market, concerned about the potential for a new round of wildfire claims, punished PG&E’s stock, and the price of a share fell from $8.10 to $3.80 over the week, cutting its market capitalization in half.

Second Time into The Breach

It wasn’t supposed to go this way.

PGE filed its Chapter 11 case – it’s second since 2000 – in January hoping to march forward with dispatch and emerge from court supervision by next June. That timing was of importance because Assembly Bill 1054, a California law signed by the Governor in July, set up a multi-billion-dollar Wildfire Fund to cover certain catastrophic claims for post-2018 wildfires. The money would come from the State’s electric utilities and their ratepayers. The statute allows PG&E to participate only if it completes its bankruptcy by the June deadline.

Eighteen months to complete its Chapter 11 proceeding was ambitious, even with lawyers who bill their time at $1,600 per hour as did PG&E’s lead counsel at Weil, Gotshal & Manges, according to fee petitions the firm filed with the Bankruptcy Court.

PG&E’s case was not only large; there were other complexities. The company remained on probation after its criminal conviction for its role in a gas pipeline explosion in San Bruno. And as a public utility, it was answerable not only to the bankruptcy court, but to the California Public Utilities Commission, an independent state agency that would need to approve any rate set in connection with the plan of reorganization.

Further complicating matters were tort claims filed by more than 50,000 creditors for property damage and personal injuries arising from twenty prior California fires, including the massive and deadly Camp Fire. Those claims had not yet been “liquidated” – that is, determined to be in a certain amount – and a separate proceeding to estimate the amount had yet to be initiated.

The Loss of Exclusivity

PG&E began its bankruptcy case with the exclusive right to propose a plan to reorganize its financial affairs. Its plan proposed to pay bondholders and other creditors and to create a fund for the wildfire claimants and insurance companies who had previously paid fire claims. PG&E’s shareholders would retain their stock, albeit diluted, and control of PG&E would remain in the hands of its current management.

But some of the hedge funds that owned PG&E bonds balked at that proposal on the grounds that it allowed old shareholders to retain too much value. Moreover, the wildfire claimants didn’t believe that the proposed fund was sufficient to cover their claims. The two groups banded together and asked the bankruptcy court to end PG&E’s exclusivity period so they might file their own plan of reorganization for PG&E.

Alternative plans are permitted in bankruptcy once the “exclusive period” has expired or been terminated, but they remain a relatively unusual development in large Chapter 11 cases, according to Matthew Hamermesh, a Philadelphia bankruptcy lawyer not involved in the case. When competing plans are authorized, a reorganization proceeding can become an all-out fight for control of the debtor, with existing management likely to be replaced if the alternative plan is confirmed.

On October 9, the bankruptcy judge granted the creditors’ request to end exclusivity, and they subsequently filed a competing plan of reorganization which proposed to increase the pot for wildfire claimants and improve the treatment of bondholders. The increases for the wildfire claimants and bondholders were, in part, funded by sharply reducing the amount available for existing shareholders.

The New Fires

The competing plans were on the table when the latest round of fires broke out in October.

While there has been no definitive determination that the Kincade Fire was caused by PG&E, the possibility of liability for more wildfire claims complicates the proceedings. Claims arising from a debtor’s operation during a bankruptcy proceeding are entitled to a higher priority than pre-bankruptcy claims, according to Hamermesh. Depending on the amount, new claims could reduce the amounts available to pay the claims of the old creditors.

Hamermesh said that the complications arising from the competing plans and potential new wildfire claims would likely cause delays, though he was optimistic that it would be “a few months one way or the other, not years and years.”

But even a delay of a few months could threaten PG&E’s hope to exit bankruptcy by June 30 and failure to do so would prevent PG&E from participating in the Wildfire Fund, at least under the terms of AB 1054.

On October 29, the Bankruptcy Judge ordered PG&E to enter into mediation with the representatives of the wildfire claimants. The stock market responded positively to the order – PG&E’s stock rose more than 30% during the day – on the possibility that mediation could result in an overall settlement that would pave the way for PG&E to exit bankruptcy with the support of its creditors and without a long delay.