On the winding highway to Half Moon Bay, a small dirt path leads up a mountain where wooden stables overlook grassy slopes with yellow flowers that welcome visitors to the Square Peg Foundation, a retirement home for former sport horses.

At one end of the stables is Sonic, a horse who steals buckets from his neighbors, and Curtis, a clubfooted racehorse who lost an eye in a stable accident. At the other end, are Bert and Panzur, who lean their heads close together.

Next to them is a huge white, 12-year-old thoroughbred with a smear of mud on his cheek. He puts his ears back, usually a sign of anger, when people come too close. But he allows Joell Dunlap, executive director of the Square Peg Foundation, to scratch where the mud has made him itchy. Meet Bruce’s Dream. Like the other horses at the Square Peg Foundation, he is also a veteran of an equestrian sport and has the injuries to prove it. To this day, he has a shoulder injury that he suffered while racing that prevents him from doing show-jumping, at which, Dunlap says he would excel given his long legs and strong back.

Leg injuries are common in horse racing. Horses’ legs are fragile and the intensity with which they run can often cause lesions that, if not identified and treated, can lead to fatal accidents on racetracks. The California Horse Racing Board’s latest annual report shows that 162 horses died in racing related activities, including training, from July 2016 to June 2017.

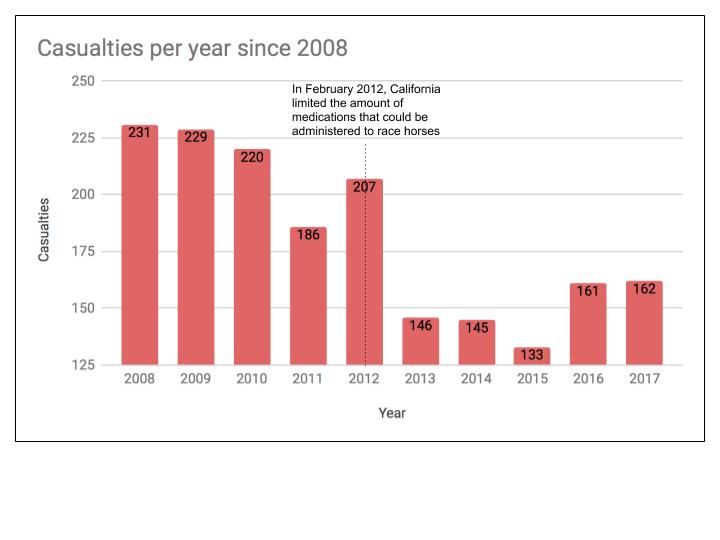

To be sure, stricter regulations and extensive efforts to understand how and why horses break down in races has made horse racing a safer sport than in years past. The number of deaths per year have gone down. Back in 2008, 231 horses died during racing or training, compared to 162 last racing season.

The lower death rate is good news for a sport that, Dunlap says, denies sentimentality despite most people in it being sentimental.

For Bruce Corwin, Bruce’s Dream’s namesake and former owner, horse racing allowed him to honor and remember his parents, who also owned racehorses. In fact, Bruce’s Dream was born to Remember Dorothy, a white mare that Corwin decided to purchase when he was grieving over the passing of his mother, Dorothy. Through Remember Dorothy and, later on, Bruce’s Dream, both white horses, Corwin felt that his mother lived on. He refers to Bruce’s Dream as his mother’s baby and remembers the excitement of his racing days with fondness.

On June 25, 2010, the horses were in their starting stalls in Hollywood Park, Calif., squeezed between two gates. They pulled at their bits, frustrated that they had been pushed into a cage. Meanwhile, the jockeys were tense on their saddles, waiting to rush out at the sound of the bell and hoping that nothing would go wrong. A misstep or a small bump from another horse could be fatal for both jockey and horse at 45 miles per hour.

In stall six, Bruce’s Dream was ready to win after nine months convalescing from an injury. On him, was Joseph Talamo, a 20-year-old jockey who dropped out of high school at 16 so he could pursue his love of horse racing and who has won more than 1,800 races. With Bruce’s Dream’s energy and Talamo’s passion, they made the perfect team.

There was little time for contemplation or fear inside the starting stall. Not even a minute passed when the gates flew open and the horses broke out with their jockeys standing on their stirrups. “They’re off!”

Sky Victor, a sleek brown horse wearing number four, took an early lead, with Bruce’s Dream in second place, a half-length behind Sky Victor.

The people that bet on number four were happy, but they couldn’t take anything for granted so early on in the race, not even when the commentator said, “Sky Victor leads the back stretch and he’s now a length and a quarter in front of Bruce’s Dream.”

Corwin, watching from the stands, shouted, “Come on grey! Come on Bruce!” He said he felt that Bruce’s Dream could still win, that he and Talamo were holding back.

After turning into the final stretch, Talamo leaned forward and Bruce’s Dream started gaining on Sky Victor. His head stretched forward and his legs became a white blur beneath him as he flew toward the finish line.

“Bruce’s Dream strikes the front and sprints away!” shouted the commentator. There was nothing Sky Victor could do. He couldn’t muster the energy to sprint in the final stretch. Bruce crossed the finish line at one minute, nine seconds, with Afleet Ruler a length behind in second place, and Sky Victor a fraction of a second behind in third place.

After nine months off the track, Bruce’s Dream was back in the winner’s circle, sweaty, with a drape of flowers over his shoulders and fans applauding his victory. Beside him, Corwin smiled like he had just won the Super Bowl.

Bruce loved racing and was always really excited to race, recalled Corwin. In his first race at age two, Bruce’s Dream was running last and then barreled his way through the other horses. He always came from behind and then sprinted at the end of a race when other horses lost speed, says Corwin.

Bruce’s Dream’s determination and competitiveness led him to the winner’s circle six times in his four-year racing career, from 2008 to 2012, earning $315,024 for the Corwins. But Bruce’s Dream raced so hard that he would hurt himself. During his four years of racing, there were long periods of isolated convalescence, especially during 2010 and 2011, when he spent most of the year recovering from the shoulder injury that he still has. It was Bruce’s Dream’s shoulder’s persistent resistance to healing that eventually convinced Corwin that it was too dangerous for Bruce’s Dream to continue competing.

Bruce’s Dream was fortunate that his injury was easily identifiable. Many horse lesions are not identified until a horse that dies on the track is necropsied. Lameness is not always observable early enough to interfere before horses that should be resting are taken out to race.

Many deaths could be avoided if pre-existing lesions could be readily identified, said Rick Arthur, the equine medical director at the California Horse Racing Board. The challenge with horse injuries is that the screening technology used on humans is not readily applied to horses. The machines are often large and noisy and require a cooperative patient that understands what is happening.

“We need alternative ways to identify injuries,” said Arthur. One alternative which has been tested is the use of nuclear scintigraphy, which uses tracer amounts of radioactive molecules to identify bone and soft tissue abnormalities. This technique can reveal any problem that a horse might have so it would be ideal for identifying the kinds of microfractures that can lead to more serious injuries. However, Richard Lewis, safety steward at Golden Gate Fields racetrack in Albany, explained that this is not a practical way to identify injuries on a day-to-day basis. It is expensive and cannot be done for every horse at every race.

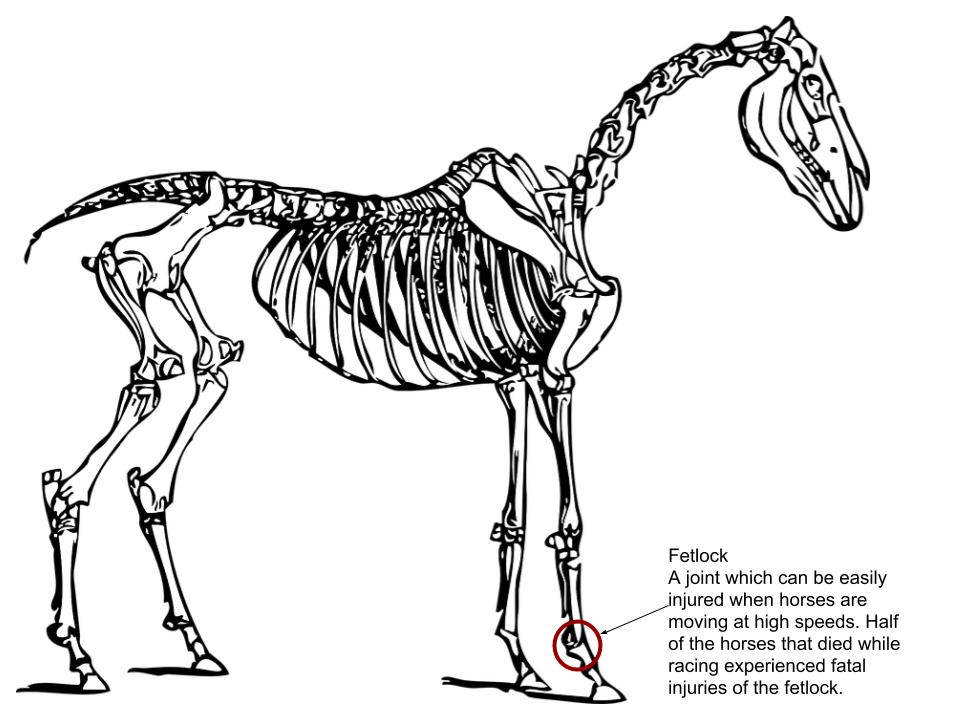

The most common injuries that can lead to fatal accidents on racetracks are injuries to the fetlock, a joint that acts as a shock absorbing mechanism in horses. “It’s almost like a spring,” explained Arthur, which allows the horse’s lower leg to absorb the horse’s weight above the hoof when it moves. The fetlock is at an angle, it is not a straight joint, which means that fractures across the bones or tears to the ligaments above, below or behind it causes the fetlock to sink down all the way to the ground. This kind of injury is generally catastrophic because the bones and ligaments around the fetlock don’t heal well because they are always under tension from carrying the weight of the horse.

According to the California Horse Racing Board’s Injury Prevention Program report, 50 percent of the horses that died in racing related activities from 2011 to 2013 had a pre-existing fetlock lesion. Humerus injuries, like Bruce’s Dream’s, were the second type of injury most likely to lead to fatal accidents while racing.

In the meantime, with no practical or accurate medical procedure to identify pre-existing lesions, the California Horse Racing Board keeps official veterinarians at all race tracks to observe horses throughout the race day. Veterinarians conduct pre-race and post-race examinations and any horse that shows signs of lameness is taken aside and examined to determine fitness for racing.

Despite best efforts, said Forrest Franklin, state veterinarian at Golden Gate Fields, “the fact of the matter is that nine out of ten of those horses that have a catastrophic injury out there, it’s very difficult for us to detect those and very difficult for the trainers to detect because these injuries exist at the microscopic level and in a very short period they go from microscopic into macroscopic injuries.”

Often, trainers, jockeys, grooms and veterinarians must depend on careful observation. Lewis said that “the key with horses is to be able to communicate with them and let them communicate with you. They don’t speak English, I don’t speak horse. So it’s done by watching them.” He explained that if one knows the horse well enough to know when it’s behaving strangely that can be a good indication that a horse shouldn’t be racing.

In the effort to reduce the number of fatal accidents, California also cracked down on abuse of medications that can mask serious pre-existing lesions. Since 2012, California cut down the amount of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that could be administered to race horses. The use of high doses of anti-inflammatory drugs can mask horses’ pain so that they can run normally despite being injured. California also prohibits the use of anabolic steroids, which are used to strengthen and energize debilitated animals so that they appear healthy when they are not.

Arthur believes stricter regulation of medications helped bring the number of accidents down after 2012. The cause for the increase in casualties in 2016 and 2017 is still being investigated, but Arthur says the 2018 data, which has not been released yet, shows a decrease in catastrophic breakdowns.

At Golden Gate Fields changing from a dirt to a synthetic track brought the number of accidents down. Lewis, the safety steward at the track, explained that on a synthetic surface, “the concussion to the horses’ front legs is decreased.” The synthetic material also retains its shape much better than dirt and drains water much more effectively. This, said Lewis, means that “there is consistency day in and day out on the footing.”

Despite the benefits of a synthetic surface, in California, only Golden Gate Fields has had success with it. “They have had nothing but problems with it at Santa Anita and Del Mar,” said Lewis, who is unsure why this has been the case. He suggests that the success at Golden Gate Fields may have something to do with how it was installed and the environment with the cooler weather. In warmer weather, like at Santa Anita near Los Angeles, the wax in the synthetic material would melt. At Santa Anita, water would also pool on the racetrack, creating a danger for horses, so it has gone back to a dirt track.

Dunlap, who is responsible for caring for the injured horses that retire from racing, said she believes that people have a responsibility to take care of thoroughbreds. “We breed thoroughbreds for our entertainment,” she said. Thoroughbreds are not a product of nature, but rather the result of humans cross-breeding Arabian stallions with English mares in the 17th century. Thus, it is a humane imperative to make sure racing doesn’t break them and that they can have a life when their racing days are over.

In 2008, California enacted legislation that automatically deducts a percentage of owners’ shares to help fund thoroughbred retirement and rehabilitation facilities like the Square Peg Foundation where Bruce’s Dream now lives.

Bruce’s Dream retired in 2012, which was when Corwin realized that Bruce’s Dream’s shoulder injury posed too high a risk for racing, and in 2016 he was sent to the Square Peg Foundation, where he now luxuriates in the sweet smell of hay and can spend his days rolling around in the mud. But it was hard for him to transition out of his racing life. When Dunlap drove him up from Los Angeles to her ranch in the mountains of Half Moon Bay, she says he kicked and neighed the whole way. The man who had taken care of Bruce’s Dream cried when he saw him leave, says Dunlap.

It took a year for Bruce’s Dream to get used to his new life among new horses and people. Dunlap thinks that because he spent a lot of time recovering from injuries without the company of other horses, he had forgotten how to be a horse. He still doesn’t get along with the other horses but he is smart and willing to learn, says Dunlap.

Those qualities have made him very successful at learning dressage, a sport that is about cooperation between rider and horse to perform intricate maneuvers that tighten horses’ movements into precision. Dressage is a controlled discipline for a horse who bet everything on expending all his energy on the explosive short minutes of a race.

“It’s a miracle that he’s turned into such a gentle giant,” says Corwin.

Bruce’s Dream may no longer be racing but the racer in him is not gone. The wildness that Corwin remembers from Bruce’s Dream’s youth is still there. When he saw a horse that he had once competed against in the same field at the Square Peg Foundation, his competitiveness resurfaced and he rammed his former rival into a fence. But in retirement, Bruce’s Dream has settled down enough to exercise with the quiet grace and focus of dressage. And at the ripe old age of 12, he even licks the hands of his handlers.