The grass at the edge of the San Francisco Bay swayed in the wind, while seagulls flew overhead the morning of June 1. Walkers, joggers and bikers passed through Shoreline Park at Mountain View on their Friday runs of the Bay Trail. A flash of brown and white might mean a snowy plover, a tiny shorebird just darted across the shoreline. If joggers are extremely lucky, they might get a glimpse of the near-threatened Ridgway’s rail, a chicken-sized bird that can only be found in the bay’s tidal marshes.

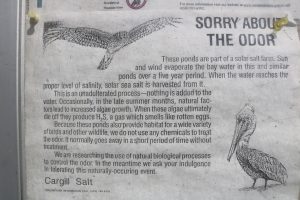

One can still read a sign from Cargill Salt, a former commercial salt producer in the area, on the park’s announcement board apologizing for the smell of rotten eggs that can still waft in when the breeze is just right. The nose-wrinkling odor comes from the natural growth of algae, which releases hydrogen sulfide during the late summer months.

The twentieth century saw a lot of salt ponds being established in what was once hundreds of thousands of acres of wetlands on the bay. These ponds, which were walled off from the bay by mud levees, were an energy-efficient way of commercially producing salt – the heat and wind during summertime were enough to evaporate the water and leave the mineral behind. Also, many coastal species have made their homes in these salty ponds. These, however, largely replaced the tidal marshes, which are critical habitats for other species and had once kept flooding in the Bay Area in check.

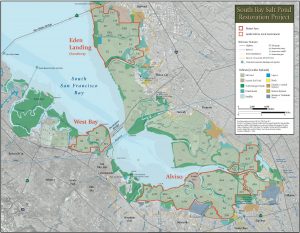

Since 2003, the South Bay Salt Pond Restoration project has been restoring over 15,000 acres of commercial salt ponds to provide habitats to coastal wildlife species and prevent flooding in the Bay Area communities. The project aims to restore 90 percent of these ponds to their original tidal marsh habitat condition and improve the flow of water between the rest of the salt ponds and the bay.

At least $35 million in funding, however, is still needed for the current phase of the project, according to Brenda Buxton, deputy bay program manager of the California State Coastal Conservancy, a state agency tasked to protect and improve natural lands and waterways along the coast and the Bay.

“These projects require a lot of earthmoving which can get very expensive,” she said.

The funding challenges of the restoration project is not an isolated case. Other conservation projects across the state, as well as state and local parks, are in need of funding.

“State parks have been starved for money since probably 2011,” said Deb Callahan, executive director of the Bay Area Open Space Council, a regional network of nonprofits and public agencies promoting the protection of parks, trails, agricultural lands and natural areas. “They need maintenance and are desperately in need for additional funding.”

Addressing conservation and climate change through Prop 68

In light of this need, Proposition 68 in Tuesday’s June primary elections in California is seeking to bolster projects that tackle water and natural resource conservation, improve park access and increase resilience to climate change. If passed, $4 billion in bonds will be allocated statewide for improvement of parks, projects on environmental protection and restoration, water infrastructure and flood protection.

The State Coastal Conservancy would receive $20 million from the total funds for the San Francisco Bay restoration, which the restoration project could tap for funding. Buxton however says even this still would have to be combined with other sources, given other projects aside from the South Bay Salt Ponds also need funding.

“[Twenty million] is not that much for wetland restoration actually,” she said.

The last multi-billion-dollar measure that got approved in California was Proposition 51 on the November 2016 ballot, which allocated $9 billion in bonds for improving and constructing facilities for K-12 schools and community colleges. Prop 68 is the only bond proposition on the June primary ballot.

Prop 68 comes as California faces increased threats of flooding, droughts and wildfires. The 2016 drought was followed by record rainfall from October 2016 to April 2017. In February 2017, San Jose residents had to evacuate their homes because of the torrential downpours that swelled Coyote Creek. Supporters of Prop 68 believe that the funding from this measure can help reduce the impacts of such adverse events.

“What’s resonating with the voters now in Prop 68 is that we’re investing in our natural resources and parks now to mitigate future impacts of climate change,” said Shelana deSilva, director of government affairs and public funding of Save the Redwoods League. For deSilva, this speaks to a change in the voting public’s mind, that climate change is less of a partisan issue, and instead is now more widely acknowledged.

Another tax on Californians?

Pushback against this proposition has come from the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association and the Republican State Senator John Moorlach, representing the 37th District of California.

Moorlach is opposing the proposition not because he thinks the projects are unimportant, but because, he says, California can afford to pay for the projects out of the state budget.

“Borrowing is a sign of fiscal mismanagement,” he said in an interview. “The proper way to deal with infrastructure is to set aside funds every year to take care of it.” For him, the issue is a matter of discipline and priorities.

“This year we have more funds in revenues than were projected, so we actually have more than $4 billion laying around. So, if this were really important to the legislature and the governor of California, then that $4 billion would be used to take care of it,” he said.

Similarly, Susan Shelley, vice president for communications of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association, cautioned that borrowing money through bonds to fund these projects would be twice as expensive as paying for these in the first place.

The Legislative Analyst’s Office, the nonpartisan fiscal and policy advisor of the state legislature, has estimated that Californians would have to pay $3.8 billion in interest over forty years of repayment, aside from the $4 billion actually borrowed.

“If we’re talking about sea level rise in a hundred years, we have enough time to pay for the projects the regular way without charging our children and grandchildren, for two generations,” said Shelley. “It would be $200 million a year [if California passed Prop 68].” For the association, projects funded by bonds should continue for as long as the state is repaying the money, which in this case is forty years.

The discussion of whether to pass Prop 68 is therefore more of a question of whether to allocate the bonds now in anticipation of climate change or to use other sources of funding available now or in the future.

California does have a history of parks bonds. According to the LAO, California voters have approved around $27 billion in bonds during statewide elections since 2000 for projects related to natural resources. Prop 68 would reallocate the unissued bonds of $100 million from three previous measures.

The office has estimated that passing the proposition would increase state bond repayment by around $200 million annually over 40 years, however, local government savings with the natural resources projects would likely be several tens of millions of dollars annually over the next few decades.

“If Prop 68 doesn’t pass, we will see serious and significant impacts,” Callahan said. Callahan likened allocating bonds to buying a car or a house when most people have to take out loans and then pay it back over time. For her, restoring the environment is a big commitment that California could not do out of its regular budget, thus the need for the bonds.

“Protecting the environment is going to be more effective now than protecting the environment in the future,” said Jennifer Koepcke, senior manager for Institutional Giving at the Peninsula Open Space Trust, which also backs the proposition.

Bay Area set to benefit recreationally, economically and environmentally

Supporters of Prop 68 point to the other benefits Californians would get from the allocated funding, aside from conservation of natural resources. DeSilva explained the importance of parks, especially the Redwoods, to the Californian life and outdoor recreation.

“Redwood parks are not only a treasured place for people to visit,” she said. “They are iconic of the state, and we should be making sure they are properly stewarded.” DeSilva also added that parks and open spaces in general support the $92 billion outdoor recreation economy of the state. Prop 68 allocates $218 million for improvements and repairs of existing state parks, such as the Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park in Humboldt County.

Businesses in the Bay Area also support the proposition since it would uphold the backbone of communities – water.

“Water underlies everything we do,” said Kendra Schultz, energy and environment associate of the Silicon Valley Leadership Group. “If there is major water insecurity, we won’t be able to support the economic and business communities and their families who are living in this area.”

Many technology companies like Facebook and Google have also made their home base on the coast of the Bay. Bay Area projects, especially the wetlands and creek restorations, funded by Prop 68 would ensure these companies, the employees and their families are protected from sea level rise and excessive flooding.

“The most cost-effective ways to try and protect cities and transportation systems from sea level rise are the natural systems. Protecting marshes will protect cities from impacts of climate change,” Callahan noted.

“The vegetation and the gentle slopes and the kind of muddy texture – when a wave hits a wetland, it will break. It’s not like hitting the wall of a levee of hitting right into our parking lots and homes or businesses,” explained Buxton. “It’s a good buffer in a storm and that I would actually say to the Bay Area is one of the greatest losses from losing all these wetlands.”

However, it is not only the business community that stands to benefit from improved water infrastructures. Residents in general also depend on water for their daily activities.

“Healthy watersheds protect the water supply and provide drinking water. They act like nature’s sponge and as the lungs of the Bay Area, and also purify water,” Callahan explained.

Buxton also mentioned that many freeways, rail lines and all of the water treatment plants are located on the edge of the Bay, all the more reason to protect the wetlands.

“You might not flood if you live up on a hill, but you won’t be able to flush your toilet,” she said.

Funding is still an issue with wetlands restoration

If the measure passes, the Bay Area would receive $61 million in funding towards projects for wetlands and riverway restoration. Regional planning for climate change adaptation – efforts towards minimizing the negative impacts of climate change and taking advantage of the positive ones – would also be funded. A third of the total funding for the area is the $20 million allocated to the State Coastal Conservancy.

Other projects that would receive funding include the Russian River, a source of drinking water for North Bay communication, and climate and conservancy programs under the San Francisco Bay Conservancy Program.

The San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority, one of the partners of the State Coastal Conservancy in the wetlands restoration, is responsible for allocating funding from Measure AA. Passed in June 2016 by the nine Bay Area counties, Measure AA generates $25 million annually for wetland restoration through a $12 parcel tax. The $20 million from Prop 68 would match the Measure AA funds.

The groups, however, are still pursuing additional funding, according to Sam Schuchat, executive officer of State Coastal Conservancy. This is especially needed, since the Prop 68 funds would still be would still be divided among the wetlands restoration projects in the Bay, including the South Bay Salt Ponds project.

Of their targeted 90 percent tidal marsh restoration, the project was able to restore 25 percent of the wetlands during its first phase from 2009 to 2016. The second phase, which is due to break ground either fall of 2018 or early 2019, will improve the work done in the past and restore at least 3,570 acres more of the wetlands.

Funding, however, for some of the sites under the second phase is still an issue. Buxton said any additional funds that would come from the proposition would be welcome, although this would certainly not be enough.

“This is really important potential keystone funding to complete the second phase,” she said.

The future of the wetlands – and Bay Area communities

Dan York, vice president of The Wildlands Conservancy, said that the United States on the national level experiences a certain disconnect between the intensive use of lands in an unrestricted way and the health of communities.

“This can be seen in the roll-back of protections in EPA and climate change deniers,” he said. “But on the state level we can still protect our resources.”

The Bay Area wetlands restoration is the just one of the projects that help natural resource conservation as well as contribute to climate change adaptation and mitigation.

“Sea level rise isn’t going to happen a hundred years from now – it’s happening right now. A hundred years from now is when it gets really bad,” said Buxton. “The next few decades we think are super critical to get these wetlands established to give them a fighting chance in the face of sea level rise.”

For Callahan, the proposition is a must-pass measure, which serves not just a special interest, but the interest of the general public.

“The longer you wait, to fix broken things, to maintain, the more expensive it’s going to cost when you get around to it,” she said.