SAN JOSE — As immigration enforcement agents picked up the pace of arrests in Northern California during the first half of 2017, local rapid response networks have swelled in membership and grown in sophistication throughout the Bay Area.

Following Donald Trump’s election, networks of civilians trained to mobilize when an undocumented resident is being arrested. This effort sprung up in anticipation of the president’s campaign promises to ramp up deportations. Recent statistics show that immigration agents have taken the first step to fulfill those promises. Across the country, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, have arrested 43 percent more people between when Trump took office and early September 2017, compared to the same period in the previous year.

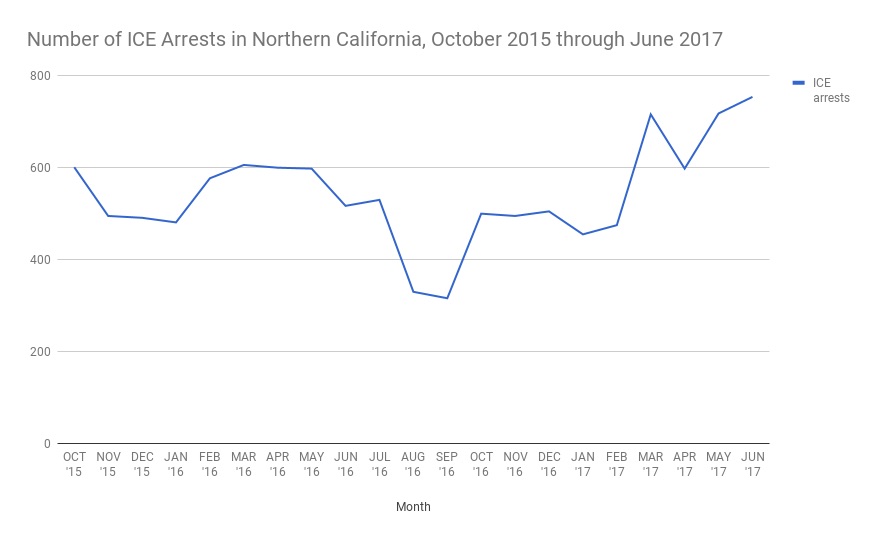

Northern California saw 10 percent more ICE arrests in the first half of 2017, with ICE agents arresting 3,710 people compared to 3,373 during the first half of 2016, KQED reported. The Northern California ICE spokesperson, James Schwab, declined repeated requests for an interview.

As awareness of ICE’s more aggressive arrest patterns has grown, so too has the receptiveness of California citizens and political leaders to protect immigrants in their own communities from deportation, according to immigration lawyer Hamid Yazdan Panah. “Things are accelerating,” Panah said in an email.

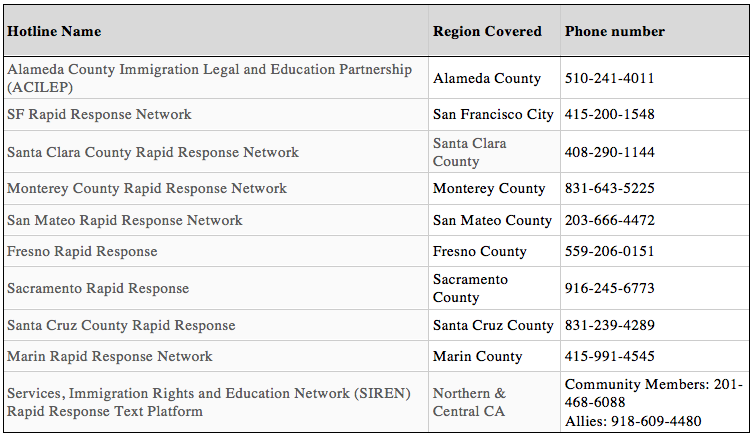

New rapid response networks now exist in Marin, Alameda, San Mateo, Santa Cruz, and Santa Clara Counties, while the City of San Francisco’s network dates back to 2008. A North Bay Rapid Response Network that will cover Sonoma and Napa counties was derailed by the fires that seared through the region in early October, but the network is expected to go live in the coming weeks.

Organizers are circulating their hotline numbers through posters and social media, so that community members know who to call when an ICE agent appears on their street or knocks on their door. Meanwhile, they are training hundreds of residents in how to verify, witness, and document immigration arrests that occur in their neighborhoods. The organizers say they hope to keep ICE agents more accountable and link the arrested person with a volunteer lawyer as quickly as possible.

Lisa Weissman-Ward, a lecturer and attorney with Stanford Law School Immigrants’ Rights Clinic, said in a phone interview that rapid response networks “serve a sort of balancing effect to preserve the right of due process” during deportation proceedings.

“They are a way to ensure that in the face of increased immigration enforcement, the community knows that there are many people that have their back…[and] that they have access to the information and counsel that they deserve [and] that they are entitled to,” said Weissman-Ward, noting that rapid response networks have grown organically from the needs and organizing of immigrant communities who best understand how to protect one another.

Panah and Weissman-Ward are also organizers for the Northern California Rapid Response Network, a still-nascent regional network that seeks to facilitate coordination between local rapid response networks and connect them with volunteer attorneys. One of the regional network’s goals, Panah said, is to create a database that documents every ICE enforcement action in Northern California – a record that doesn’t currently exist publicly.

This comes at a time when the clash over immigration between democratic leaders in California and the Trump administration has escalated into a dizzying sparring match – and the threat of large-scale immigration raids targeted at California looms large.

On October 5, Gov. Jerry Brown signed the so-called sanctuary state law (SB-54), which will limit cooperation and information sharing between local and state law enforcement and ICE agents as of Jan. 1.

A day later, ICE Acting Director Tom Homan said in response: “ICE will have no choice but to conduct at-large arrests in local neighborhoods and at worksites, which will inevitably result in additional collateral arrests.”

Just two weeks before, immigration agents arrested nearly 500 unauthorized immigrants, in a four-day sweep that specifically targeted cities and counties with existing sanctuary policies to limit local law enforcement agents from questioning and detaining people suspected of immigration violations, according to an ICE press release. Agents arrested 21 in Santa Clara County and six in San Francisco, while 101 were arrested in Los Angeles. As the operation demonstrated, sanctuary policies can’t prevent the federal government from using its own resources to enforce federal immigration law.

The “Safe City” operation and Homan’s threats of at-large arrests raised the specter of worksite immigration raids, which ICE conducted regularly during President George W. Bush’s administration. Those raids often resulted in the arrest of hundreds – or even thousands — of workers at a time. Today, Bay Area rapid response networks are gearing up for more large-scale raids of this kind.

While ICE did not conduct large-scale worksite raids during President Barack Obama’s two terms, targeted enforcement operations were common and ICE deported 2.75 million during Obama’s presidency – a number which exceeded that of any president before him and earned him the title “deporter in chief” from critics. Obama directed ICE to prioritize noncitizens with criminal records as well as recent border crossers, whose numbers surged during his presidency. (Border apprehensions have dropped precipitously each month since Trump’s election, amounting to an overall decrease of 24 percent between October 2016 and August 2017 compared to the same period the year prior, according to data provided by US Customs and Border Protection.)

On his fifth day in office, Trump signed a sweeping executive action that greatly expanded the type of person that ICE goes after. Now, anyone who had entered the country illegally, especially those with a prior order of deportation, are fair game. Arrests of these so-called “non-criminal immigration violators” have increased nearly three-fold between Jan. 22 and Sept. 2 compared to the same period the year prior.

Under Trump, there has also been an increase in so-called “collateral arrests” of people without legal status that ICE encounters along the way while targeting a pre-specified individual. During a nationwide sweep in late July ostensibly targeting unaccompanied minors and families, 70 percent of the 650 people arrested were in fact not part of the original target, but rather “encountered during this operation,” according to an ICE press release.

“The only thing that we can do is try to take them seriously and be prepared,” said attorney Jessica Therkelsen in a phone interview. Therkelsen, who works with a San Francisco legal innovation lab called OneJustice, has worked to map and contact about 150 active rapid response programs throughout the state. But while the state’s pro-immigrant resources have grown rapidly in the past year, she points to major gaps in Northern and Eastern California, where few trained immigration lawyers exist among large populations of undocumented immigrants.

Therkelsen added that it’s now more likely that people get arrested, processed and deported very quickly due to Trump’s new enforcement priorities, without stating their case in front of a judge. This, she said, is the “deportation machine in which they may not ever have the time, resources or opportunity to ever say why it is that they should be given a chance.”

Immigration agents typically arrest people before dawn when neighbors, family members and lawyers are still sleeping. Without third-party witnesses, the likelihood that an ICE agent acts unconstitutionally goes up, said Weissman-Ward, citing cases in which agents forced entry without a judicial warrant, called themselves police instead of immigration agents, wore plain clothes instead of uniforms, or used force or a display of arms to intimidate people to open their doors or answer questions.

“It’s happening quite literally in the dark,” she said of ICE arrests.

Then, once a person has been arrested and placed into custody, they are not guaranteed paid counsel during their deportation proceedings, unlike in criminal court. Some struggle to get in contact with their families, let alone a lawyer. In some cases, they can be deported in a matter of days. Without a lawyer, “it’s the federal government against someone who has no counsel,” Weissman-Ward said. “You can’t have access to justice without counsel.”

Bay Area rapid response organizers say they’ve faced little resistance, and local governments have heartily endorsed the grassroots networks. In a phone interview, Stephanie Jayne of the City of San Jose’s Office of Immigrant Affairs, herself a rapid responder, emphasized that people should feel empowered to call the hotline, even if they only suspect that they see ICE, because “we would rather be safe than sorry.”

At a training held in San Jose on Oct. 8, 13 residents became the newest rapid responders to join the Santa Clara County Rapid Response Network, which is organized by Sacred Heart Community Service and People Acting in Community Together, or PACT, both faith-based grassroots organizations. About a dozen local partner organizations sponsor the network and promote its 24/7 hotline, which went live across the entire county in late August.

Since March, the network’s organizers have led 27 trainings throughout the county, training over 600 community members.

“We want to know that every time that ICE shows up to the community, our community’s there to support the impacted family,’’ said training leader Rosa De Leon.