The water rushed under a fence and through the sandbags meant to deter it. It rose to doorsteps, collecting at a depth of three feet in some places. It damaged property and trapped residents inside, keeping them from work.

The Le Mar Trailer Park in Redwood City was flooded. Again.

The repeated flooding of Le Mar exemplifies a pernicious double bind: those with the fewest resources are zoned into living in the most dangerous area.

The events of Feb. 7 were nothing new for residents. In fact, this wasn’t even a particularly bad flood. Deborah Crivello, the manager of Le Mar and a resident of the park next door, described it more as a “scare” than a flood, since the water lasted for a few days, not weeks, this time and only collected in a few low-lying spots, rather than “filling it [the park] up.” Another resident called the flooding “puddles” compared to other times. Those puddles were at least two feet deep in places.

Although many residents continue to be frustrated, the city has taken a number of measures to help in the last few years. Crivello says the efforts have shown, and that she remembers when the situation was much worse.

The time that stands out most was twenty years ago. She had recently moved in to the park next door, although she was not yet manager at Le Mar.

Police pounding on her door woke Crivello up in the middle of the night. She stood there in pajamas, her husband and baby still asleep inside, as police officers yelled at her family to get out of their house. Grease and oil from the junkyard down the street was mixed in with the water, and it was dangerous to stay. They had five minutes to gather their things.

“I opened the door and my stairs were floating,” she said. She carried her daughter on her back as she waded through waist-deep water. The water remained for two weeks, during which she stayed at the nearby V.A. When she returned, she found that her car had been ruined; the water had been up to its windows.

She remembers being frustrated that no one had explained the risk of flooding in the area to her before that night.

“I wouldn’t have moved in if I’d knew that was going to happen.” She laughed. “But now I know.”

But what exactly is there to know? Why is it, that in a time of regional drought, this neighborhood has experienced flooding at such a rate that “puddle” has become appropriate shorthand for two feet of standing water?

In order to understand Le Mar’s situation it is important to zoom out. This rectangle of asphalt wedged between the wetlands and a busy highway sits at the intersection of a number of environmental and governmental forces.

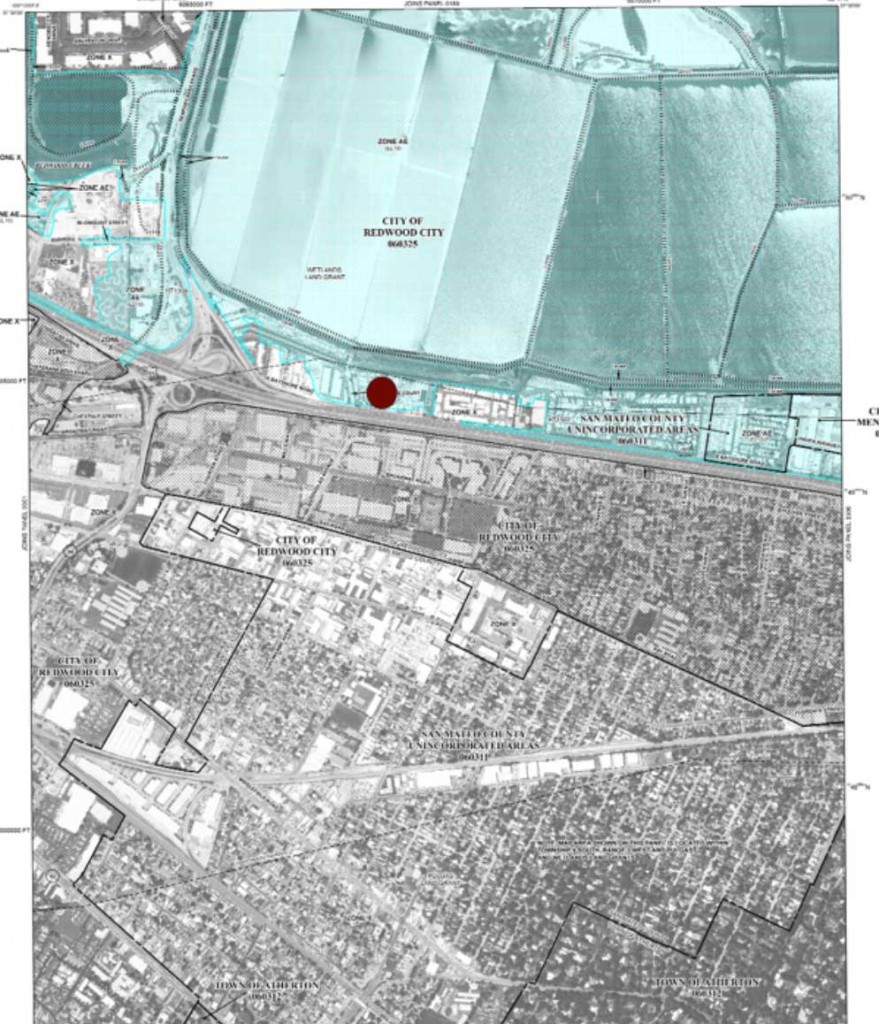

The topography of Le Mar makes it particularly vulnerable to flooding. The mobile home park is one of the few developed areas of Redwood City that has been classified as “special flood hazard area” by FEMA. The majority of this area, in light blue in the map, is a wetland preserve.

These zones are designated by the federal government to discourage development, so as to avoid having people live in dangerous areas, according to Susan Cutter, a professor at University of South Carolina who has conducted extensive research on natural hazard risks.

“What normally happens, however, is that those high-hazard areas actually have the most affordable land because of the hazard, and the affordability of the land means that people from lower incomes can reside in those areas,” she said.

This is coupled by a particular vulnerability to the ravages of natural hazards, like flooding, among these groups. Wealthier people have more safety nets like insurance or additional bank accounts to dip into when they experience a hazard, Cutter says. But the unexpected cost of repairs and replacements can throw a major wrench into a tight budget.

That’s exactly what happened to Crivello, who lost her car because she didn’t have the kind of full coverage that would replace it.

Even worse, mobile home residents have a particular vulnerability to environmental hazards because their houses are less sturdy than other housing stock, according to Cutter.

A mobile home could “float away in a flood, conceivably,” she said.

So then why is it, that in Redwood City the very residents who can be hurt most by natural hazards live closest to these environmental forces?

It is not just because the land is cheaper, but also because it is the only place these sort of residences are legally allowed to exist.

Mobile home parks are a particular zoning designation according to the Redwood City municipal code. And, as is clear in a zoning map obtained from the city website, there is a very limited amount of land that allows mobile home parks. All of it sits within the high-risk flooding area. In the map below, mobile home areas are indicated in brown. The red dot indicates Le Mar.

In Redwood City, mobile home parks are only permitted in high-risk flood areas.

Jonathan Levine, a professor at the University of Michigan and author of “Zoned Out: Regulation, Markets, and Choices in Transportation and Metropolitan Land Use,” says that while there are many good uses for zoning, like keeping people’s homes separate from the noise and odor of industrial areas, there is also an “insidious history” of measures separating different “kinds of people” by housing type. This means an apartment building or duplex may not be allowed to be next to a single-family home. Or that there may be restrictions on where you can live if your house is a mobile home rather than a permanent building.

William Chui, an assistant planner at the Community Development Department of Redwood City, said he was not sure if the mobile home parks were built in this area particularly because of zoning, or if the zoning laws were written because the parks were already there. He said the city could not do much to tell owners of private property to modify the land to reduce the effects of flooding, unless there was a development project planned. The exception to that would be the canal, which is government property.

The city ensures the canal is dredged every year so that the water flows freely towards the bay, and can store as much as possible. It has also added sand bags and concrete blocks between the edge of the canal and the park to mitigate overflow, according to Ramana Chinnakotla, Redwood City’s public works director. He said the city also has gas-powered pumps, which are far more effective than the electric pumps Le Mar currently owns, to propel water flowing into the park back into the canal.

Crivello credits the reduction in flooding over the last few years to these efforts, adding that she was very grateful after a decade and a half of residents dealing with the flooding on their own.

But these city measures are not always enough, as Feb. 7 made clear. Although the pumps help prevent smaller floods, Crivello said that when the water is really high and the canal is overflowing into the park, pumping water back into the canal creates an unproductive cycle.

“It’s just pouring into the canal to pour it back out [into the park],” she said. She is disappointed that other measures she had been promised, including a steel fence that would prevent water from getting into the park, have not been implemented.

Chinnakotla said this was a valid concern, which was why the city was working towards a more “permanent solution.” He said the steel fence was scrapped because it would have taken too much time to get approved, and that he is instead working towards building a storage area for the water to flow into before it makes its way to the bay. He said he has been working on this idea for years, and is currently waiting for it to be approved so he can move forward.

Meanwhile, most Le Mar residents seem to know little about why the flooding continues year after year. Raul Acosta, 18, whose family has lived in Le Mar his entire life, said that neighbors discuss property damage, but never why it happens.

“People only really talk about it in the first few days that it happens, then it’s business as usual, I guess,” he said.

So it is today. As I talk to Acosta, he keeps an eye on his little sister as she twirls around her front yard in a princess dress, playing with the toys that all had to be replaced two years ago. During that flood, right before Christmas, the water had reached all the way to his home, which is roughly a city-block’s distance from the fence.

The sun sparkles on the pavement, and except for a few puddles around potted plants — likely from over-zealous watering more than anything — today the ground is dry. A few cats zigzag across the pavement, sauntering slowly, then randomly bolting across the way, as if they hear something we can’t on this quiet afternoon.

But beyond the sleepy scene, beyond the fence surrounding the property, the canal still runs high with water, a subtle reminder that any day, storm clouds could build in the distance, come rumbling through and disrupt life here once again.